Also by Ngg wa Thiongo

FICTION

Wizard of the Crow

Petals of Blood

Weep Not, Child

The River Between

A Grain of Wheat

Devil on the Cross

Matigari

SHORT STORIES

Secret Lives

PLAYS

The Black Hermit

This Time Tomorrow

The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (with Micere Mugo)

I Will Marry When I Want (with Ngg wa Mri)

PRISON MEMOIR

Detained: A Writers Prison Diary

ESSAYS

Something Torn and New

Decolonising the Mind

Penpoints, Gunpoints, and Dreams

Moving the Centre

Writers in Politics

Homecoming

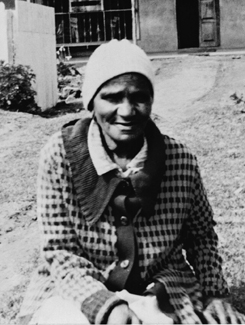

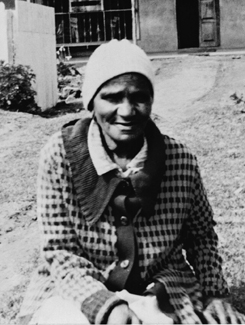

Wanjik wa Ngg, the authors mother

For Thiongo senior, Kmunya, Ndc, Mkoma, Wanjik, Njoki, Bjrn, Mmbi, Thiongo K, and niece Ngna in the hope that your children will read this and get to know their great-grandmother Wanjik and great-uncle Wallace Mwangi, a.k.a. Good Wallace, and the role they played in shaping our dreams.

There is nothing like a dream to create the future.

VICTOR HUGO , Les Misrables

I have learnt

from books dear friend

of men dreaming and living

and hungering in a room without a light

who could not die since death was far too poor

who did not sleep to dream, but dreamed to change the world.

MARTIN CARTER , Looking at Your Hands

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing

About the dark times.

BERTOLT BRECHT , Motto

Years later when I read T. S. Eliots line that April was the cruelest month, I would recall what happened to me one April day in 1954, in chilly Limuru, the prime estate of what, in 1902, another Eliot, Sir Charles Eliot, then governor of colonial Kenya, had set aside as White Highlands. The day came back to me, the now of it, vividly.

I had not had lunch that day, and my tummy had forgotten the porridge I had gobbled that morning before the six-mile run to Knyogori Intermediate School. Now there were the same miles to cross on my way back home; I tried not to look too far ahead to a morsel that night. My mother was pretty good at conjuring up a meal a day, but when one is hungry, it is better to find something, anything, to take ones mind away from thoughts of food. It was what I often did at lunchtime when other kids took out the food they had brought and those who dwelt in the neighborhood went home to eat during the midday break. I would often pretend that I was going someplace, but really it was to any shade of a tree or cover of a bush, far from the other kids, just to read a book, any book, not that there were many of them, but even class notes were a welcome distraction. That day I read from the abridged version of Dickenss Oliver Twist. There was a line drawing of Oliver Twist, a bowl in hand, looking up to a towering figure, with the caption Please sir, can I have some more? I identified with that question; only for me it was often directed at my mother, my sole benefactor, who always gave more whenever she could.

Listening to stories and anecdotes from the other kids was also a soothing distraction, especially during the walk back home, a lesser ordeal than in the morning when we had to run barefoot to school, all the way, sweat streaming down our cheeks, to avoid tardiness and the inevitable lashes on our open palms. On the way home, except for those kids from Ndeiya or Ngeca who had to cover ten miles or more, the walk was more leisurely. It was actually better so, killing time on the road before the evening meal of uncertain regularity or chores in and around the home compound.

Kenneth, my classmate, and I used to be quite good at killing time, especially as we climbed the last hill before home. Facing the sloping side, we each would kick a ball, mostly Sodom apples, backward over our heads up the hill. The next kick would be from where the first ball had landed, and so on, competing to beat each other to the top. It was not the easiest or fastest way of getting there, but it had the virtue of making us forget the world. But now we were too big for that kind of play. Besides, no games could beat storytelling for capturing our attention.

We often crowded around whoever was telling a tale, and those who were really good at it became heroes of the moment. Sometimes, in competing for proximity to the narrator, one group would push him off the main path to one side; the other group would shove him back to the other side, the entire lot zigzagging along like sheep.

This evening was no different, except for the route we took. From Knyogori to my home village, Kwangg or Ngamba, and its neighborhoods we normally took a path that went through a series of ridges and valleys, but when listening to a tale, one did not notice the ridge and fields of corn, potatoes, peas, and beans, each field bounded by wattle trees or hedges of kei apple and gray thorny bushes. The path eventually led to the Khingo area, past my old elementary school, Manguo, down the valley, and then up a hill of grass and black wattle trees. But today, following, like sheep, the lead teller of tales, we took another route, slightly longer, along the fence of the Limuru Bata Shoe factory, past its stinking dump site of rubber debris and rotting hides and skins, to a junction of railway tracks and roads, one of which led to the marketplace. At the crossroads was a crowd of men and women, probably coming from market, in animated discussion. The crowd grew larger as workers from the shoe factory also stopped and joined in. One or two boys recognized some relatives in the crowd. I followed them, to listen.

He was caught red-handed, some were saying.

Imagine, bullets in his hands. In broad daylight.

Everybody, even we children, knew that for an African to be caught with bullets or empty shells was treason; he would be dubbed a terrorist, and his hanging by the rope was the only outcome.

We could hear gunfire, some were saying.

I saw them shoot at him with my own eyes.

But he didnt die!

Die? Hmm! Bullets flew at those who were shooting.

No, he flew into the sky and disappeared in the clouds.

Disagreements among the storytellers broke the crowd into smaller groups of threes, fours, and fives around a narrator with his own perspective on what had taken place that afternoon. I found myself moving from one group to another, gleaning bits here and there. Gradually I pieced together strands of the story, and a narrative of what bound the crowd emerged, a riveting tale about a nameless man who had been arrested near the Indian shops.

The shops were built on the ridge, rows of buildings that faced each other, making for a huge rectangular enclosure for carriages and shoppers, with entrance-exits at the corners. The ridge sloped down to a plain where stood African-owned buildings, again built to form a similar rectangle, the enclosed space often used as a market on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The goats and sheep for sale on the same two market days were tethered in groups in the large sloping space between the two sets of shopping centers. That area had apparently been the theater of action that now animated the group of narrators and listeners. They all agreed that after handcuffing the man, the police put him in the back of their truck.