Thanks to the Chapman family, and especially to Bettys daughter, for the use of documents, tapes, photographs and other materials relating to the life of this extraordinary woman. Thanks also to The History Press, and especially to Mark Beynon, and to Nigel West for his foreword.

C ONTENTS

BY N IGEL W EST

E arly in March 1980 I found myself in Claygate, south-west London, in the company of an elderly British army officer, Major Michael Ryde, who had fallen on hard times. I was meeting him because I had heard that during the war he had served in MI5 as a Regional Security Liaison Officer, the post held by the organisations representatives who acted as an intermediary between the counter-espionage branch, designated B Division, and individual military district commanders. Over a cup of coffee served by his long-suffering partner, Marjorie Caton-Jones, Ryde recalled his recruitment into the Security Service and happier times, when he routinely had been engaged in the most secret work, much of it involved in the handling of double agents. As he gained enthusiasm for his subject, and his improving memory allowed him to add the kind of detail that ensures authenticity, these revelations visibly moved Marjorie who confided to me later that in all the years she had lived with the veteran, he had never mentioned his wartime intelligence role. As a professional journalist of long standing, having worked on The Sunday Telegraph for years, she had developed a skill for listening, and on this occasion she sat rapt as the man she had known and lived with described a part of his life that hitherto had been entirely unknown to her. Later, she would reproach herself for having failed to apply her inquiring mind to the one man who had played such an important part in her recent life.

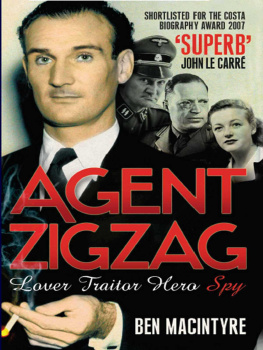

Major Rydes story largely revolved around his relationship with a Nazi spy, code named Fritzchen, who had been expected to parachute into East Anglia towards the end of December 1942. Much was already known about him at MI5s headquarters in St Jamess Street, information that had been gleaned from ISK and ISOS, the cryptographic source based on intercepts of the Abwehrs internal communications. The German training school in Nantes, where Fritzchen had been based, was connected to Berlin by a radio link as the occupiers learned to distrust the French landline telephone system. With regional operations supervised in every detail from the Abwehrs main building on the Tirpitzufer, the airwaves were entrusted with the most banal details of the progress made by agents undergoing preparation for missions in enemy territory. Fritzchen was known to be a British renegade, paid a regular monthly salary of 450 Reichsmarks, with an agreed bonus of 100,000 Reichsmarks, then valued at 15,000, if he pulled off his sabotage assignment successfully. As well as mentioning his contractual arrangements, the intercepts listed the two aliases he would adopt in England, the frequencies of his wireless transmitter and the detail of his dental repairs.

In Fritzchens case, his planned departure was delayed by a training accident when he had been injured while practising a parachute drop. After several false alarms, Ryde had been alerted to the imminent arrival of the much-anticipated spy on a clandestine Luftwaffe flight from Le Bourget in mid-December, and he finally landed near Ely on the night of 20 December, three days late. Ryde had been waiting patiently for this news, but he could not be certain of the exact location of the drop-zone, nor the likely attitude of the spy. Worst case, Fritzchen, who was known to have a criminal past, would prove to be intransigent and uncooperative, making MI5s task more complicated. On the other hand, he might be wholly willing to collaborate, and then there was always the middle path, of the spy conditioned to self-preservation, who would take on whatever guise that would save him from the gallows.

Ryde recalled the moment, in Littleports tiny police station, that the Chief Constable of Cambridgeshire had ushered him into the interview room where he was confronted with Fritzchen, the first Nazi spy of his acquaintance, and who was equipped with 1,000 in notes, a loaded automatic and a suicide pill. This would be the beginning of an extraordinary adventure that would end in January 1946 when MI5 learned that the double agent known to them as Zigzag intended to disclose his remarkable story in the French newspaper LEtoile du Soir. The result was a criminal prosecution at the Old Bailey on charges under the Official Secrets Act in an attempt to remind Zigzag, and other double agents also tempted to recount their experiences. MI5s leading lawyer, Edward Cussen KC, discussed the options at length with his Director of B Division, Guy Liddell, who confided to the diary he dictated every evening that authority had been given for Cussen to travel to Paris to investigate what was regarded as a significant breach of faith.

Cussen returned to London with the evidence required to arrest Zigzag, and it was intended that a private session in a magistrates court, held in camera, with a stern lecture from the bench, would act as a deterrent, not just for Zigzag, but for any others interested in publishing indiscreet memoirs. However, MI5s intentions were thwarted when, to the surprise of the prosecuting counsel, the defence had called Major Michael Ryde, who had testified on oath at his trial at Bow Street Court on 19 March, without any approval from MI5, that the defendant was the bravest man he had ever met and that, far from deserving to be in the dock, he should receive a medal. Thus ended Rydes career in the Security Service, and gave Eddie Chapman the confidence to tell his truly incredible tale.

Thanks to Michael Ryde, and an introduction provided by him, I was soon sharing coffee with Eddie Chapman and his equally extraordinary wife, Betty, at their apartment in the Barbican. Always modest about his own exploits, the legendary double agent regarded his encounters with MI5 as only a small part of an extraordinary career. Fortunately, Betty knew better!

I was introduced to Betty and Eddie Chapman several years before Eddies passing in 1997, by Lilian Verner-Bonds, a mutual friend and a long-time friend of the Chapmans. One of my great regrets is that I didnt know more about Eddie at the time. Sketchy details of his past were known, but my recollection of that first meeting is of a pleasant, late-middle-age couple in their comfortable but far from extravagant surroundings. We shared a pleasant tea together, during which the conversation passed as nothing remarkable, leaving me with a recollection of a nice gentleman who said very little. As the years passed, so too Eddie passed away. I was encouraged over a long period to start writing the story of his wife Betty, which is equally remarkable. The time was never right, until now.

This book was constructed from numerous interviews, documents, Bettys notebooks spanning several decades, and from taped reminiscences of Betty and Eddie, which were generously provided by the Chapman family. Other information has come from documentary sources. In her nineties, Betty is still bright and lucid, with an excellent memory. Where possible, this story has been told in her own words: my role is principally that of narrator. Where Bettys language may, in a very few places, seem politically incorrect, it must be remembered that she is a woman of her generation: a woman of substance by dint of her own efforts, and a British woman living through the transition from British Empire to Commonwealth. I have never, through long interviews and in examining innumerable pages of her notes and writings, seen the faintest hint of prejudice. This is especially true as she describes her adventures in Africa and the Middle East. She simply reports what she has seen and done, and takes all who she met as they are, on their own merits.