()

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

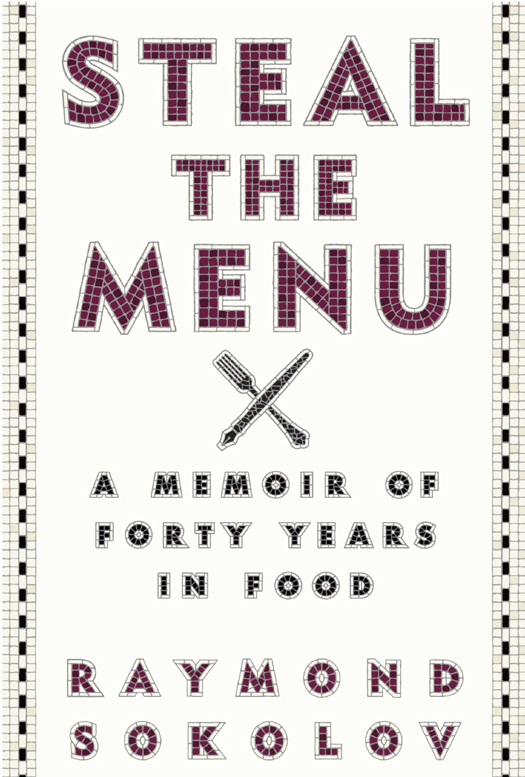

Copyright 2013 by Raymond Sokolov

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

The New York Times: The articles A Food Critic Appraises Meals at 3 Prisons, Taste of Dog Food Appraised, Warning, It May Not Work, and excerpts from the articles: Drivers Who Stop Only for Gas Dont Know What Theyre Missing, For the Citys Best in Chinese Cuisine, The Great Cake Controversy Continued, Its Worth Saving Up for a Taste of This Culinary Splendor, Leaders of the Chinese Taste Revolution: Those Elusive Chefs, Mexican Cuisine Goes from Delicate to Fiery, Off on a Gastronomic Voyage of Discovery, Pheasant Family-Style, Standards at Pearls Have Slipped a Bit, and Where They Know How to Cook Pasta, by Raymond Sokolov. Reprinted by permission of The New York Times.

The New York Times: Excerpt from Just What Julie Nixon NeedsScouring Pads and a Cookbook by Charlotte Curtis (November 27, 1968). Reprinted by permission of The New York Times.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

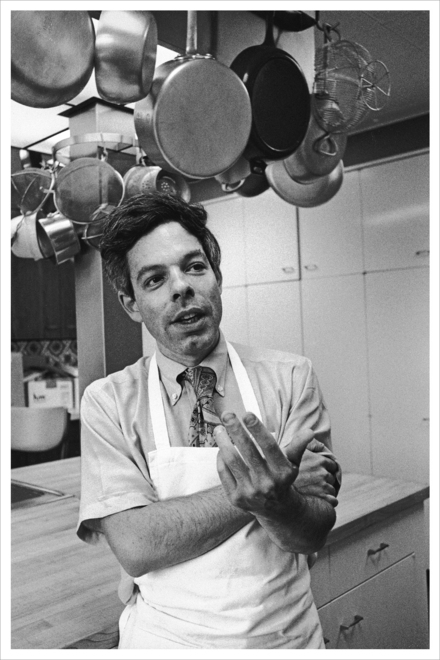

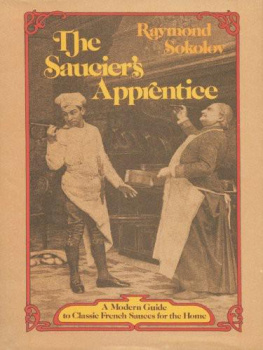

Sokolov, Raymond A.

Steal the menu : a memoir of forty years in food / by Raymond Sokolov.

First edition.

pages cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-96247-8

1. Sokolov, Raymond A. 2. CooksUnited StatesBiography 3. Food writing. 4. Cooking, American. I. Title.

TX 649. S 57 S 65 2013

641.5092dc23

[B] 2012044156

Jacket design by Jon Valk

v3.1

For Johanna

Contents

ONE

First Bites

TWO

The Ungastronomical Me

THREE

Food News

FOUR

Upstairs in Front

FIVE

With Reservations

Amuse-Bouche

Theres too much bay leaf in this soup, said Craig Claiborne, after sloshing the tomato-pea pure mongole around in his mouth. He and I and Charlotte Curtis, his boss, were having lunch in the cafeteria of the New York Times in the spring of 1971. Craig was retiring as food editor of the Times after fourteen years in the job. He was a self-made legend, trained as a chef and a reporter, who had transformed the newspapers food department from a sleepy recipe mill into a broad and lively forum for glamorous profiles of chefs, reports on the citys ethnic cooks and reviews of New York restaurants. He thought he could privatize his celebrity and his omnivorous yet rigorous approach to food with a personal newsletter about restaurants and cooking. Charlotte, in a huge gamble, had hired me as his successor.

Theres too much bay leaf in this soup, said Craig Claiborne, after sloshing the tomato-pea pure mongole around in his mouth. He and I and Charlotte Curtis, his boss, were having lunch in the cafeteria of the New York Times in the spring of 1971. Craig was retiring as food editor of the Times after fourteen years in the job. He was a self-made legend, trained as a chef and a reporter, who had transformed the newspapers food department from a sleepy recipe mill into a broad and lively forum for glamorous profiles of chefs, reports on the citys ethnic cooks and reviews of New York restaurants. He thought he could privatize his celebrity and his omnivorous yet rigorous approach to food with a personal newsletter about restaurants and cooking. Charlotte, in a huge gamble, had hired me as his successor.

Curtis was another Times legend. A midwestern socialite with hair pulled back tight, she was a newsroom lifer. As womens news editor, in charge of a big and increasingly important area, she presided over the Family/Style page, where Craigs articles appeared. In her earlier Times career, as a society reporter, Charlotte had made readers smile with her tart flair for skewering vapid brides in her coverage of big-time weddings.

In an account of a shower for Julie Nixon prior to her marriage to David Eisenhower, Charlotte wrote, And by afternoons end, [Richard Nixons younger daughter] was knee-deep in such essentials as sachets made to look like roses, scented candles, bookends and a silver engraving of her wedding invitation. The article skipped on insouciantly to a dinner-dance at the Waldorf Towers, where President Nixon joined Julies young pals during a break from appointing cabinet secretaries. In four impeccably factual words about the presidential drop-in, Charlotte summarized the man himself: He did not dance.

Craig, a gentlemanly native of Sunflower, Mississippi, had parlayed a degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and a diploma from a Swiss hotel school into the Times food job. His shrewd instincts for capitalizing on the new craze for food had transformed a sleepy, creaky womans-page service feature into a glamorous star turn. It had also made him rich.

Back in 1960, when Craig had been food editor for only three years and Times management hadnt yet realized theyd spawned a monstre sacr in their food department, Craig requested permission to use the Times name and its sacrosanct Times logo for a cookbook to be entitled The New York Times Cookbook. According to legend, barely concealing a smirk, the papers managing editor, Turner Catledge, waved the young man onto delirious success.

Harper & Row had never stopped selling the book.

How much did Craig owe to the Times connection? I inclined to the cynical, if unprovable, view that without that logo and the official-sounding title, the book would not have gone anywhere merely on the strength of the relatively unknown authors name.

By 1971, however, Craig had made a name for himself, at least among Times readers. He believed he could sail on happily without the Times and without sweating deadlines for four features every week. He could, he believed, continue his reign as New Yorks food czar in independent splendor. I took him to think that some lesser being would man the food-beat treadmill at the paper, reinforcing by his jejune mediocrity the myth of the matchless Craig.

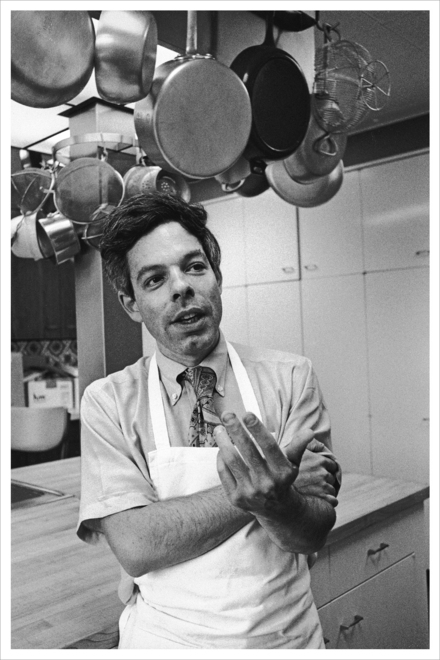

And I was going to be that man.

In Craigs world, I was indeed a nobody. Id never taken a cooking class, published a restaurant review or written a recipe. My credentials as a cultural journalist at Newsweek, where I was currently working, were honorable; not too long before Id been on the short list to become the Times lead book critic. But in the kitchen, I was a cipher. However, the ego of a child prodigy had kept me from seeing that I had no business at this table, in this cafeteria, with Craig Claiborne and Charlotte Curtis.

When Craig commented on the bay leaf in the pure mongole, I sneered inwardly. Couldnt he see how ridiculous it was to play the gourmet with an old-fashioned soup made in a corporate cafeteria kitchen? This was the place the New Yorkers resident gastronome and press critic, A. J. Liebling, had mocked in a jab he once took at newspaper editors:

they come to newspapers like monks to cloisters or worms to apples. They are the dedicated. All of them are fated to be editors except the ones that get killed off by the lunches they eat at their desks until even the most drastic purgatives lose all effect upon them. The survivors of gastric disorders rise to minor executive jobs and then major ones, and the reign of these nonwriters makes our newspapers read like the food in The New York Times cafeteria tastes.

Did Craig think hed give me a bad moment with his bay leaf gambit? Actually, I now think he was just surrendering to the reflex of commenting expertly about the food in front of him, just as he had in print for seven hundred Fridays. In any case, I knew that my palate couldnt have detected a heavy hand with bay leaf in that soup. And from now on Id be expected to uncover serious chefs omissions and commissions, to unmask them with confidence for an audience of demanding

Theres too much bay leaf in this soup, said Craig Claiborne, after sloshing the tomato-pea pure mongole around in his mouth. He and I and Charlotte Curtis, his boss, were having lunch in the cafeteria of the New York Times in the spring of 1971. Craig was retiring as food editor of the Times after fourteen years in the job. He was a self-made legend, trained as a chef and a reporter, who had transformed the newspapers food department from a sleepy recipe mill into a broad and lively forum for glamorous profiles of chefs, reports on the citys ethnic cooks and reviews of New York restaurants. He thought he could privatize his celebrity and his omnivorous yet rigorous approach to food with a personal newsletter about restaurants and cooking. Charlotte, in a huge gamble, had hired me as his successor.

Theres too much bay leaf in this soup, said Craig Claiborne, after sloshing the tomato-pea pure mongole around in his mouth. He and I and Charlotte Curtis, his boss, were having lunch in the cafeteria of the New York Times in the spring of 1971. Craig was retiring as food editor of the Times after fourteen years in the job. He was a self-made legend, trained as a chef and a reporter, who had transformed the newspapers food department from a sleepy recipe mill into a broad and lively forum for glamorous profiles of chefs, reports on the citys ethnic cooks and reviews of New York restaurants. He thought he could privatize his celebrity and his omnivorous yet rigorous approach to food with a personal newsletter about restaurants and cooking. Charlotte, in a huge gamble, had hired me as his successor.