Copyright 2012 by Jean Zimmerman

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zimmerman, Jean.

Love, fiercely : a gilded age romance / Jean Zimmerman.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-15-101447-7

1. Stokes, Edith Minturn, 18671937. 2. Stokes, I. N. Phelps (Isaac Newton Phelps), 18671944. 3. Minturn family. 4. Stokes family. 5. Socialites New York (State)New YorkBiography. 6. ArchitectsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 7. Social reformersNew York (State)Biography. 8. Rich peopleNew York (State) New YorkBiography. 9. Artists modelsNew York (State) New YorkBiography. 10. New York (N.Y.)Biography. I. Title.

F 128.47. Z 56 2012

974.7'0410922dc23

[B] 2011036976

Book design by Victoria Hartman

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Maud

Prologue

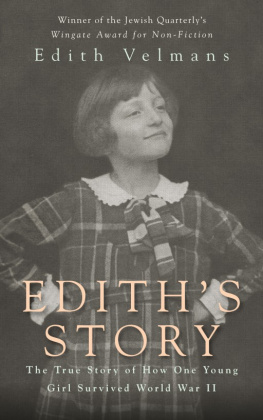

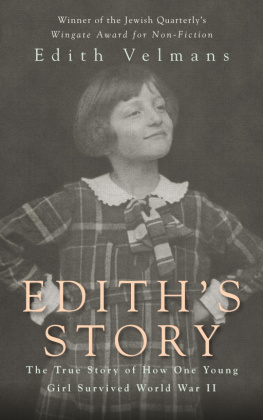

I saw her for the first time in a work of art. John Singer Sargent painted Edith Minturn Stokes in 1897, one of the soaring, seven-foot-tall canvases that made the American-born artist the most sought-after portraitist of his day.

This portrait was different, because Edith Minturn was different.

I remember encountering the painting in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in a room hung with a half-dozen Sargent women, the Wyndham sisters posed against banks of peonies, Charlotte Louise Burckhardt pinching a rose between two delicate fingers, Mrs. Hugh Hammersley in a gold-trimmed gown of dusty-pink velvet.

Marvelous paintings, to be sure. But the subjects, all of them, to a woman, of their time. Remote. Victorian females, belles of the belle poque. I could admire them, but they could not engage me, not in the way that Edith did. Her face made me stop in front of the painting, in front of her. Sargent had caught a quality of gleaming freshness that rendered his subject disturbingly alive.

More than anything else, I recognized her. The sense of insouciance and independence that swirled around her was familiar. She reminded me of myself as a thirty-year-old. Edie Minturnthats what they called her when she was youngcould have been my contemporary. In the painting, she embodies the quality of being stingingly, vivaciously alive. Her brother had nicknamed her Fiercely in her youth, and that was how she first appeared to me.

Fiercely.

I had actually gone to the Met in search of the other person in the Sargent portrait, Ediths husband, I. N. Phelps Stokes. He was the author of one of the most astonishing books ever created on the early history of a city, the sprawling, labyrinthine and maddening tome called The Iconography of Manhattan Island. A massive undertaking, six volumes, 3,254 pages, collecting together everything that would otherwise have been lost about early Manhattan, pictures and drawings and maps, a priceless repository of our knowledge of New York City.

Obscure as the Iconography was to modern readersit exists today primarily on the shelves of research librariesI fell in love with its strange, postmodernist attempt to encompass a place fully within the pages of a book. It reminded me of something out of Borgess famous infinite library, or of a trope by the comedian Steven Wright, about a map that grew to the same size as the place it was attempting to chart. I sought to find out all I could about the remarkable man who had created this huge, baggy monster of a book.

In the Sargent painting, Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes stands behind his wife, caught in a skein of shadow. By far the most arresting figure in the portrait is the woman. In reviews and notices, and in the publics view, the husband figured hardly at all.

T HE CIRCUMSTANCES OF the portrait were thus. On their wedding day, in August 1895, both groom and bride were a well-ripened twenty-eight, relatively ancient for marriage in that period. Two years later, in 1897, they interrupted their sojourn in Paris (a honeymoon that would last almost three years) and traveled to London. On a sunny afternoon in June, Newton and Edith presented themselves at Sargents studio in Tite Street.

Obsessive about costume, Sargent selected a gown of blue satin for his subject to wear. Edie dressed herself, and the artist began. It gradually became clear that something was wrong. The great man painted, the subject posed. But Sargent realized he was missing it, missing her. After repeated sittings, he had something of the dress, the face. But the elements did not go together. The parts did not add up to a whole.

Finally, one day, Edith and Newton arrived at the studio for a sitting in what passed for their street clothes. They had been around town all morning. Afterward, it was said they had come from tennis, but this turns out not to be true. Ediths complexion flushed with exertion. Glowing, as the euphemism has it, perspiring or, more candidly, sweating.

Sargent pulled up, transfixed by the image she offered. Beginning again, he depicted Edith as he had none of his subjects before, in an informal, modern ensemble, caught in the moment. He captured the essence of a woman who was truly different from the ladies hed previously painted, in their silks and satins, posed in fancy drawing rooms. He must have known the picture would resonate with her, that she would accept his unorthodox interpretation. Yet the finished portrait set off a flurry of debate in its day, recognized as a depiction of something new under the sun.

Even though I had gone on pilgrimage to the painting in order to find him, and discovered her instead, I gradually came to see the portrait not as I first encountered it, as a painting of a singular woman, but one that told the story of a couple, and a timeManhattan at the turn of the last century. From the year of their birth, 1867, to the year of their marriage, 1895, Edith and Newton Stokes lived in a nation swept up by one of historys greatest explosions of wealth, power, creativity and empire. During that remarkable span of time, twenty-five million newcomers from other shores poured into the country, Bell invented the telephone, Edison developed electric light and railroad tycoon Leland Stanford drove the golden spike into the ground at Promontory Point. Eight states were added to the Union. Great fortunes were either created or extended.

Edith and Newton were New York City to the bone. He, raised in an Italianate residence at Madison Avenue and 37th Street, which after his time there would become J. P. Morgans townhouse and then a celebrated museum of the arts. She, born a little farther afield, in still countrified Staten Island. They were in love and in Manhattan, which represents an unparalleled state of bliss. They led not so much independent as interdependent lives. Newton, the man in the shadows, was an antiquarian and aesthete who created a masterpiece, his lifes work, the Iconography. Edith too became accomplished, though in quite a different sense. I saw her first in a Sargent painting, but most of Gilded Age America encountered her beauty in the visage of a colossal statue, a figure representing the Republic, which adorned the entrance of the Worlds Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago.

Icon and iconographer. A couple, a place, a time. Edith and Newton would last forty years together, a crucial stretch of a burgeoning countrys history. They reached great heights, experienced much the age had to offer in the way of wealth and experience, and then lost everything except each other. Theirs might be the greatest love story never told.

PART ONE

1. Enchanted Woods

Next page