Oliver Sacks - The Island of the Colorblind

Here you can read online Oliver Sacks - The Island of the Colorblind full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1998, publisher: Vintage, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

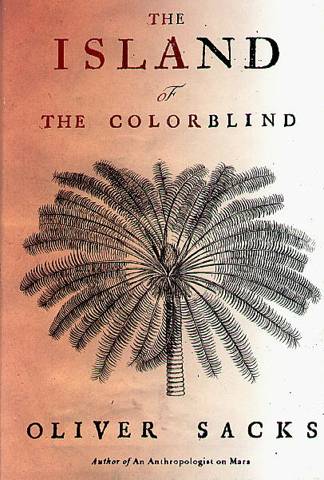

- Book:The Island of the Colorblind

- Author:

- Publisher:Vintage

- Genre:

- Year:1998

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Island of the Colorblind: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Island of the Colorblind" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Island of the Colorblind — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Island of the Colorblind" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

|

Oliver Sacks

The Island of the Colorblind

And Cydad island

1996

Oliver Sacks has always been fascinated by islandstheir remoteness, their mystery, above all the unique forms of life they harbor. For him, islands conjure up equally the romance of Melville and Stevenson, the adventure of Magellan and Cook, and the scientific wonder of Darwin and Wallace.

Drawn to the tiny Pacific atoll of Pingelap by intriguing reports of an isolated community of islanders born totally color-blind, Sacks finds himself setting up a clinic in a one-room island dispensary, where he listens to these achromatopic islanders describe their colorless world in rich terms of pattern and tone, luminance and shadow. And on Guam, where he goes to investigate the puzzling neurodegenerative paralysis endemic there for a century, he becomes, for a brief time, an island neurologist, making house calls with his colleague John Steele, amid crowing cockerels, cycad jungles, and the remains of a colonial culture.

The islands reawaken Sacks lifelong passion for botanyin particular, for the primitive cycad trees, whose existence dates back to the Paleozoicand the cycads are the starting point for an intensely personal reflection on the meaning of islands, the dissemination of species, the genesis of disease, and the nature of deep geologic time. Out of an unexpected journey, Sacks has woven an unforgettable narrative which immerses us in the romance of island life, and shares his own compelling vision of the complexities of being human.

T his book is really two books, independent narratives of two parallel but independent journeys to Micronesia. My visits to these islands were brief and unexpected, not part of any program or agenda, not intended to prove or disprove any thesis, but simply to observe. But if they were impulsive and unsystematic, my island experiences were intense and rich, and ramified in all sorts of directions which continually surprised me.

I went to Micronesia as a neurologist, or neuroanthropolo-gist, intent on seeing how individuals and communities responded to unusual endemic conditions a hereditary total colorblindness on Pingelap and Pohnpei; a progressive, fatal neurodegenerative disorder on Guam and Rota. But I also found myself riveted by the cultural life and history of these islands, their unique flora and fauna, their singular geologic origins. If seeing patients, visiting archeological sites, wandering in rain forests, snorkelling in the reefs, at first seemed to bear no relation to each other, they then fused into a single unpartition-able experience, a total immersion in island life.

But perhaps it was only on my return, when the experiences recollected and reflected themselves again and again, that their connection and meaning (or some of their meanings) started to grow clear; and with this, the impulse to put pen to paper. Writing, in these past months, has allowed me, forced me, to revisit these islands in memory. And since memory, as Edelman reminds us, is never a simple recording or reproduction, but an active process of recategorization of reconstruction, of imagination, determined by our own values and perspectives so remembering has caused me to reinvent these visits, in a sense, constructing a very personal, idiosyncratic, perhaps eccentric view of these islands, informed in part by a lifelong romance with islands and island botany.

From my earliest years I had a passion for animals and plants, a biophilia nurtured first by my mother and my aunt, then by favorite teachers and the companionship of school friends who shared these passions: Eric Korn, Jonathan Miller, and Dick Lindenbaum. We would go plant-hunting together, vascula strapped to our backs; on frequent freshwater expeditions, at dawn; and for a fortnight of marine biology at Millport each spring. We discovered and shared books I got my favorite Strasburgers Botany (I see from the flyleaf) from Jonathan in 1948, and innumerable books from Eric, already a bibliophile. We spent hundreds of hours at the zoo, at Kew Gardens, and in the Natural History Museum, where we could be vicarious naturalists, travel to our favorite islands, without leaving Regents Park or Kew or South Kensington.

Many years later, in the course of a letter, Jonathan looked back on this early passion, and the somewhat Victorian character which suffused it: I have a great hankering for that sepia-tinted era, he wrote. I regret that the people and the furniture about me are so brightly colored and clean. I long endlessly for the whole place suddenly to be plunged into the gritty monochrome of 1876.

Eric felt similarly, and this is surely one of the reasons why he has come to combine writing, book collecting, book buying, book selling, with biology, becoming an antiquarian with a vast knowledge of Darwin, of the whole history of biology and natural science. We were all Victorian naturalists at heart.

In writing about my visits to Micronesia, then, I have gone back to old books, old interests and passions I have had for forty years, and fused these with the later interests, the medical self, which followed. Botany and medicine are not entirely unallied. The father of British neurology, W.R. Gowers, I was delighted to learn recently, once wrote a small botanical monograph on Mosses. In his biography of Gowers, Macdonald Critchley remarks that Gowers brought to the bedside all his skill as a natural historian. To him the neurological sick were like the flora of a tropical jungle.

In writing this book, I have travelled into many realms not my own, and I have been greatly helped by many people, especially those people of Micronesia, of Guam and Rota and Pingelap and Pohnpei patients, scientists, physicians, botanists whom I encountered on the way. Above all, I am grateful to Knut Nordby, John Steele, and Bob Wasserman for sharing the journey with me, in many ways. Among those who welcomed me to the Pacific, I must thank in particular Ulla Craig, Greg Dever, Delihda Isaac, May Okahiro, Bill Peck, Phil Roberto, Julia Steele, Alma van der Velde, and Marjorie Whiting. I am grateful also to Mark Futterman, Jane Hurd, Catherine de Laura, Irene Maumenee, John Mollon, Britt Nordby, the Schwartz family, and Irwin Siegel for their discussions of achromatopsia and of Pingelap. Special thanks are due to Frances Futterman, who, among other things, introduced me to Knut and provided invaluable advice on selecting sunglasses and equipment for our expedition to Pingelap, in addition to sharing her own experience of achromatopsia.

I am likewise indebted to many researchers who have played a part in investigating the Guam disease over the years: Sue Daniel, Ralph Garruto, Carleton Gajdusek, Asao Hirano, Leonard Kurland, Andrew Lees, Donald Mulder, Peter Spencer, Bert Wiederholt, Harry Zimmerman. Many others have helped in all sorts of ways, including my friends and colleagues Kevin Cahill (who cured me of amebiasis contracted in the islands), Elizabeth Chase, John Clay, Allen Furbeck, Stephen Jay Gould, G.A. Holland, Isabelle Rapin, Gay Sacks, Herb Schaumburg, Ralph Siegel, Patrick Stewart, and Paul Theroux.

My visits to Micronesia were greatly enriched by the documentary film crew which accompanied us there in 1994, and shared all of these experiences with us (and got a great many of them on film, despite often difficult conditions). Emma Crichton-Miller, first, provided a great deal of research on the islands and their people, and Chris Rawlence produced and directed the filming with infinite sensitivity and intelligence. The film crew Chris and Emma, David Barker, Greg Bailey, Sophie Gardiner, and Robin Probyn enlivened our visit with skill and camaraderie, and not least as friends, who have now accompanied me on many different adventures.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Island of the Colorblind»

Look at similar books to The Island of the Colorblind. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Island of the Colorblind and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.