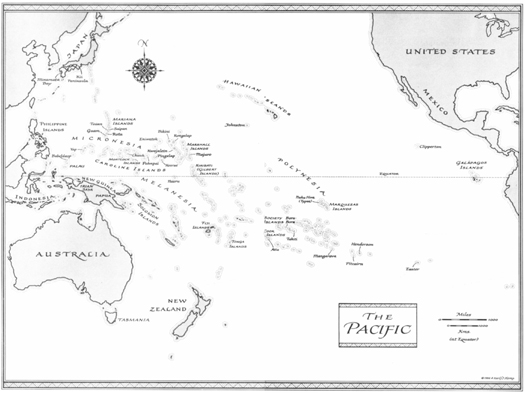

Click for a larger version of this image.

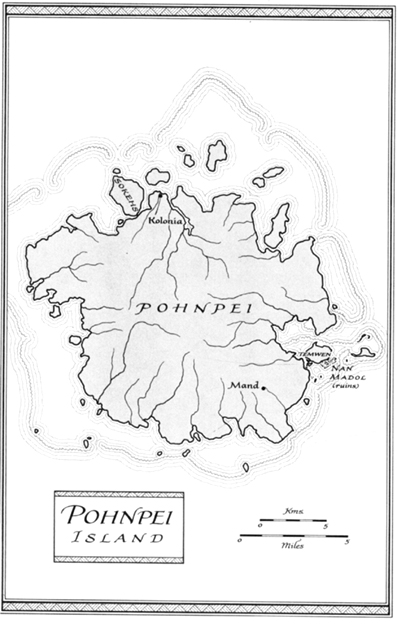

Click for a larger version of this image.

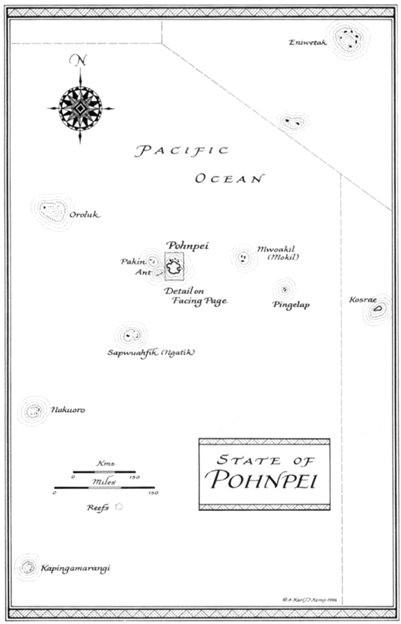

Click for a larger version of this image.

VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JANUARY 1998

Copyright1996 by Oliver Sacks

Maps copyright1996 by Anita Karl / James Kemp

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Published in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in hardcover in somewhat different form in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1996.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Douglas Goode for permission to reproduce the illustration on .

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Sacks, Oliver W.

The island of the colorblind / Oliver Sacks.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-345-80589-8

1. Color blindnessCaroline Islands. 2. ParkinsonismGuam. 3. DementiaGuam. 4. Medical anthropologyOceania. I. Title.

RE921.S23 1997

617.75909966dc20 96-34252

CIP

Vintage ISBN: 0-375-70073-0

Random House Web address: www.randomhouse.com

v3.1

For Eric

Contents

Book I

THE ISLAND OF THE COLORBLIND

Book II

CYCAD ISLAND

List of Illustrations

Preface

T his book is really two books, independent narratives of two parallel but independent journeys to Micronesia. My visits to these islands were brief and unexpected, not part of any program or agenda, not intended to prove or disprove any thesis, but simply to observe. But if they were impulsive and unsystematic, my island experiences were intense and rich, and ramified in all sorts of directions which continually surprised me.

I went to Micronesia as a neurologist, or neuroanthropologist, intent on seeing how individuals and communities responded to unusual endemic conditionsa hereditary total colorblindness on Pingelap and Pohnpei; a progressive, fatal neurodegenerative disorder on Guam and Rota. But I also found myself riveted by the cultural life and history of these islands, their unique flora and fauna, their singular geologic origins. If seeing patients, visiting archaeological sites, wandering in rain forests, snorkelling in the reefs, at first seemed to bear no relation to each other, they then fused into a single unpartitionable experience, a total immersion in island life.

But perhaps it was only on my return, when the experiences recollected and reflected themselves again and again, that their connection and meaning (or some of their meanings) started to grow clear; and with this, the impulse to put pen to paper. Writing, in these past months, has allowed me, forced me, to revisit these islands in memory. And since memory, as Edelman reminds us, is never a simple recording or reproduction, but an active process of recategorizationof reconstruction, of imagination, determined by our own values and perspectivesso remembering has caused me to reinvent these visits, in a sense, constructing a very personal, idiosyncratic, perhaps eccentric view of these islands, informed in part by a lifelong romance with islands and island botany.

From my earliest years I had a passion for animals and plants, a biophilia nurtured first by my mother and my aunt, then by favorite teachers and the companionship of school friends who shared these passions: Eric Korn, Jonathan Miller, and Dick Lindenbaum. We would go plant-hunting together, vascula strapped to our backs; on frequent freshwater expeditions, at dawn; and for a fortnight of marine biology at Millport each spring. We discovered and shared booksI got my favorite Strasburgers Botany (I see from the flyleaf) from Jonathan in 1948, and innumerable books from Eric, already a bibliophile. We spent hundreds of hours at the zoo, at Kew Gardens, and in the Natural History Museum, where we could be vicarious naturalists, travel to our favorite islands, without leaving Regents Park or Kew or South Kensington.

Many years later, in the course of a letter, Jonathan looked back on this early passion, and the somewhat Victorian character which suffused it: I have a great hankering for that sepia-tinted era, he wrote. I regret that the people and the furniture about me are so brightly colored and clean. I long endlessly for the whole place suddenly to be plunged into the gritty monochrome of 1876.

Eric felt similarly, and this is surely one of the reasons why he has come to combine writing, book collecting, book buying, book selling, with biology, becoming an antiquarian with a vast knowledge of Darwin, of the whole history of biology and natural science. We were all Victorian naturalists at heart.

In writing about my visits to Micronesia, then, I have gone back to old books, old interests and passions I have had for forty years, and fused these with the later interests, the medical self, which followed. Botany and medicine are not entirely unallied. The father of British neurology, W. R. Gowers, I was delighted to learn recently, once wrote a small botanical monographon Mosses. In his biography of Gowers, Macdonald Critchley remarks that Gowers brought to the bedside all his skill as a natural historian. To him the neurological sick were like the flora of a tropical jungle.

In writing this book, I have travelled into many realms not my own, and I have been greatly helped by many people, especially those people of Micronesia, of Guam and Rota and Pingelap and Pohnpeipatients, scientists, physicians, botanistswhom I encountered on the way. Above all, I am grateful to Knut Nordby, John Steele, and Bob Wasserman for sharing the journey with me, in many ways. Among those who welcomed me to the Pacific, I must thank in particular Ulla Craig, Greg Dever, Delihda Isaac, May Okahiro, Bill Peck, Phil Roberto, Julia Steele, Alma van der Velde, and Marjorie Whiting. I am grateful also to Mark Futterman, Jane Hurd, Catherine de Laura, Irene Maumenee, John Mollon, Britt Nordby, the Schwartz family, and Irwin Siegel for their discussions of achromatopsia and of Pingelap. Special thanks are due to Frances Futterman, who, among other things, introduced me to Knut and provided invaluable advice on selecting sunglasses and equipment for our expedition to Pingelap, in addition to sharing her own experience of achromatopsia.

I am likewise indebted to many researchers who have played a part in investigating the Guam disease over the years: Sue Daniel, Ralph Garruto, Carleton Gajdusek, Asao Hirano, Leonard Kurland, Andrew Lees, Donald Mulder, Peter Spencer, Bert Wiederholt, Harry Zimmerman. Many others have helped in all sorts of ways, including my friends and colleagues Kevin Cahill (who cured me of amebiasis contracted in the islands), Elizabeth Chase, John Clay, Allen Furbeck, Stephen Jay Gould, G. A. Holland, Isabelle Rapin, Gay Sacks, Herb Schaumburg, Ralph Siegel, Patrick Stewart, and Paul Theroux.