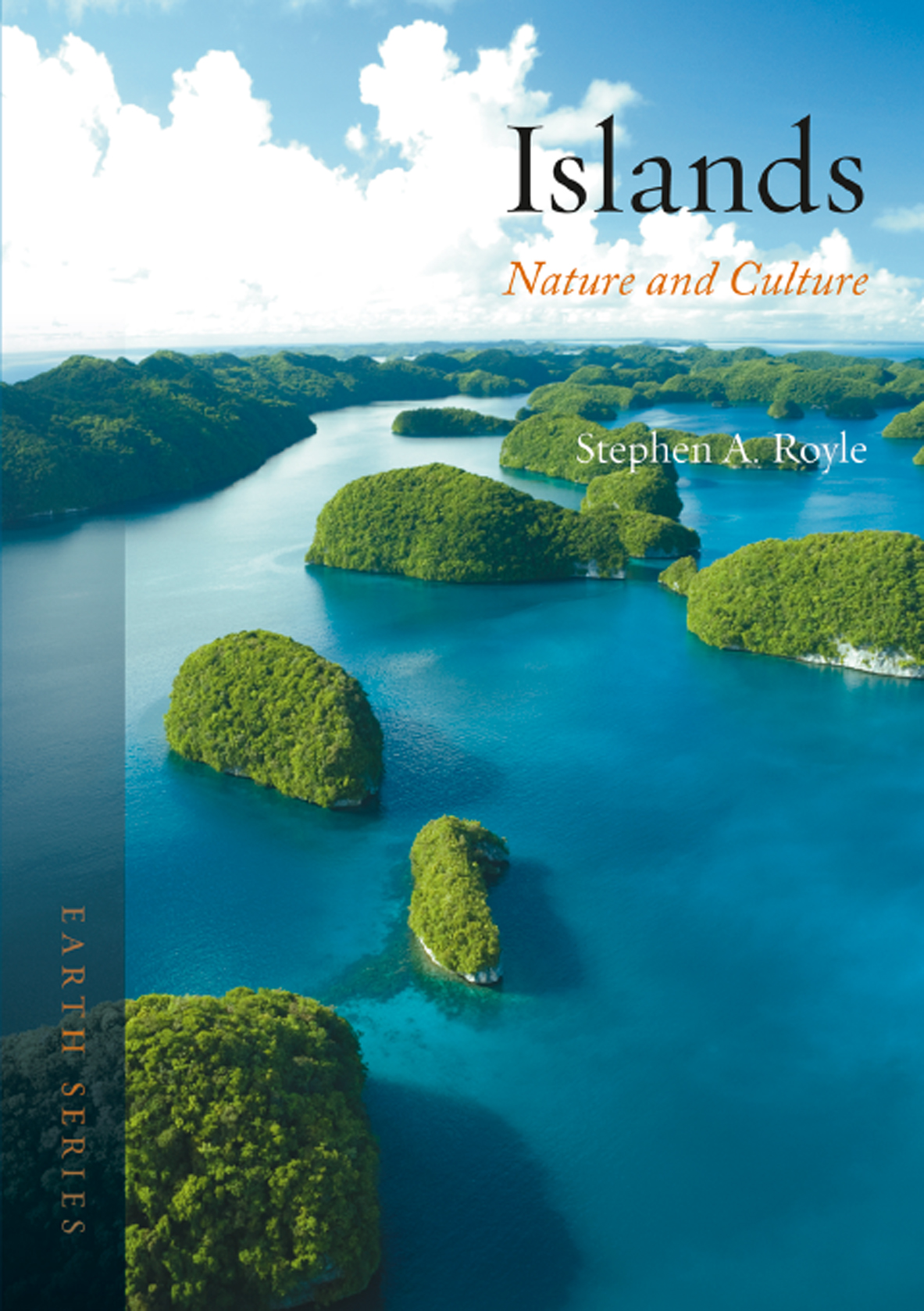

ISLANDS

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

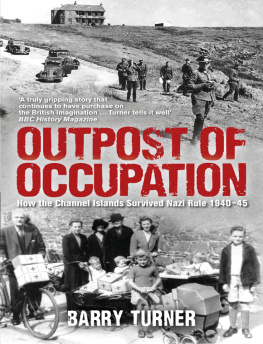

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Moon Edgar Williams

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Islands

Stephen A. Royle

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright Stephen A. Royle 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234014

CONTENTS

Nathaniel Hone (18311917), View on the Irish coast, probably Lambay Island, from Malahide; view from the shore looking towards the sea and to an island, n.d., watercolour.

1 Islands: Definition and Formation

What is an island?

The portion of the English word island that refers to insularity is the first syllable. Its sound is reflected in part of the place names of many small islands off Great Britain and Ireland that have -ay or -ey endings: Anglesey, Dursey, Jersey, Lambay, Raasay, Shapinsay, Whalsay and so on. This ending stems from the voyages of the Vikings or Norse in this region from the eighth to eleventh centuries, when these peoples were expanding their arena of activity from their Scandinavian home. In this era the sea was a highway, not a barrier, and islands were ports of call where fresh water might be obtained and rest, relaxation and perhaps refuge might be sought. The Vikings toponymic mark on these islands comes from the Old Norse word for island, ey; modern Danish has . Islands with -ey endings do not normally take island as part of their names, for this would be tautological it is Jersey, not Jersey Island. The Old Norse ey entered English via the Old English e or , not by itself (although there is an island near Dublin called Irelands Eye) but in combination with land, a solid part of the earth, to form iland. This had happened by AD 888, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. In 1624 John Donne actually wrote no man is an iland, the s in island becoming common only later that century, though the pronunciation did not alter.

The English, being a seafaring and trading people, needed other words to describe different types or groups of islands and their language offers archipelago, atoll, crag, eyot, holm, isle, islet, key (cay), reef, rock and skerry. Other languages needed fewer terms if the sea and the pieces of land within it were of less importance to their speakers. Slovak, from landlocked Slovakia in Eastern Europe, has only one word for island, ostrov, with developments therefrom, such as ostrovan for islander and sostrovie for archipelago.

To the Vikings a piece of land surrounded by water was not an ey unless it was sufficiently distant from the mainland for the passage separating it to be navigable by a ship with its rudder in place. In the Scottish census of 1861 an island had to have enough pasture to support at least one sheep. That same year, upon signing the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the UK, in acknowledgement that it was not habitable, abandoned the claim to an exclusive zone around Rockall, which must thus be regarded as a rock or crag, not an island.

Francis Towne, view of the coast of the isle of Lundy, 1787, watercolour.

Eigg, a true Scottish island with pasturage for many sheep.

Another definition issue relates to periodic islands: bodies of land cut off, usually daily, by tidal movements. Is Holy Island (Lindisfarne) off northeast England an island? A slick answer might be yes and no, depending on whether the tide is in or not. However, to visit Lindisfarne is certainly to become enisled, for it has a different feel and ethos to the neighbouring mainland. This is partly because Lindisfarne, though retaining some agriculture and fishing, is a tourism hotspot, with its economy and retail outlets geared towards visitors in a way not shared by the mainland. Further, visitor and islander both are restricted in accessing or leaving the island by the tides; functionally no different to waiting for a ferry.

Rockall, whose status as part of Scotland has been disputed.

The causeway to Lindisfarne on the northeast coast of England. Note the refuge platform in the distance, to serve in the event of stranding.

What of islands with a bridge, causeway or tunnel connecting them to the mainland? The sea might still surround the island, but functionally fixed links change islands into peninsulas. However, a fixed link might not remove insular identity, as examples from the Maritime Provinces in eastern Canada demonstrate. Cape Breton Island was joined to the rest of Nova Scotia in 1955 when the Canso Causeway was opened but its residents identified still with the island; there is a story of an old lady thanking God for having at last made Canada a part of Cape Breton.have occasionally made the crossing in winter in canoes, dragging them over the ice if necessary. In 1775 and 1777 the governor of what was then a separate British colony persuaded islanders to carry mail to the mainland in the same way, so the authorities could truthfully report to potential settlers that the island was not closed off from the outside world in winter. By the mid-nineteenth century more substantial iceboats made the journey, sailing across open stretches and being dragged on runners over solid ice. Such trips were dangerous; in 1855 one was halted by poor ice conditions and a blizzard after nine hours, 4 km (2.5 miles) short of the island. The four crew, three passengers and a dog took refuge on a solid floe and were carried eastwards. In the morning they decided to return to the mainland but had to spend a second night on the ice. The next day a young passenger died, as did the dog, which was slaughtered for food. Landfall was eventually made in Nova Scotia 40 km (25 miles) east of the starting point. The survivors were frostbitten; the man who had lost his dog had also lost his toes.

![Greek islands [2018]](/uploads/posts/book/209249/thumbs/greek-islands-2018.jpg)