The Evening Land

By Seamus Heaney

From Connemara, or the Moher clifftop,

Where the land ends with a sheer drop,

You can see three stepping stones out of Europe.

Anchored like hulls at the dim horizon

Against the winds and the waves explosion.

The Aran Islands are all awash.

East coastlines furled in the foams white sash.

The clouds melt over them like slush.

And on Galway Bay, between shore and shore,

The ferry plunges to Aranmore.

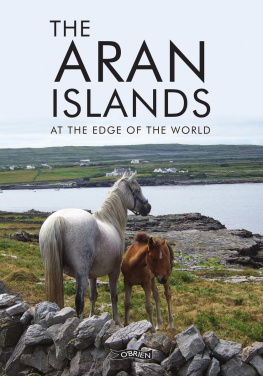

The Aran Islands are a group of windswept, grey rock ledges off the west coast of Ireland. Creeping one by one away from the Connacht mainland, and facing the open Atlantic, they harbour memories of ancient Ireland, the history and traditions of Gaelic culture, and the spirit, songs and stories of an island people.

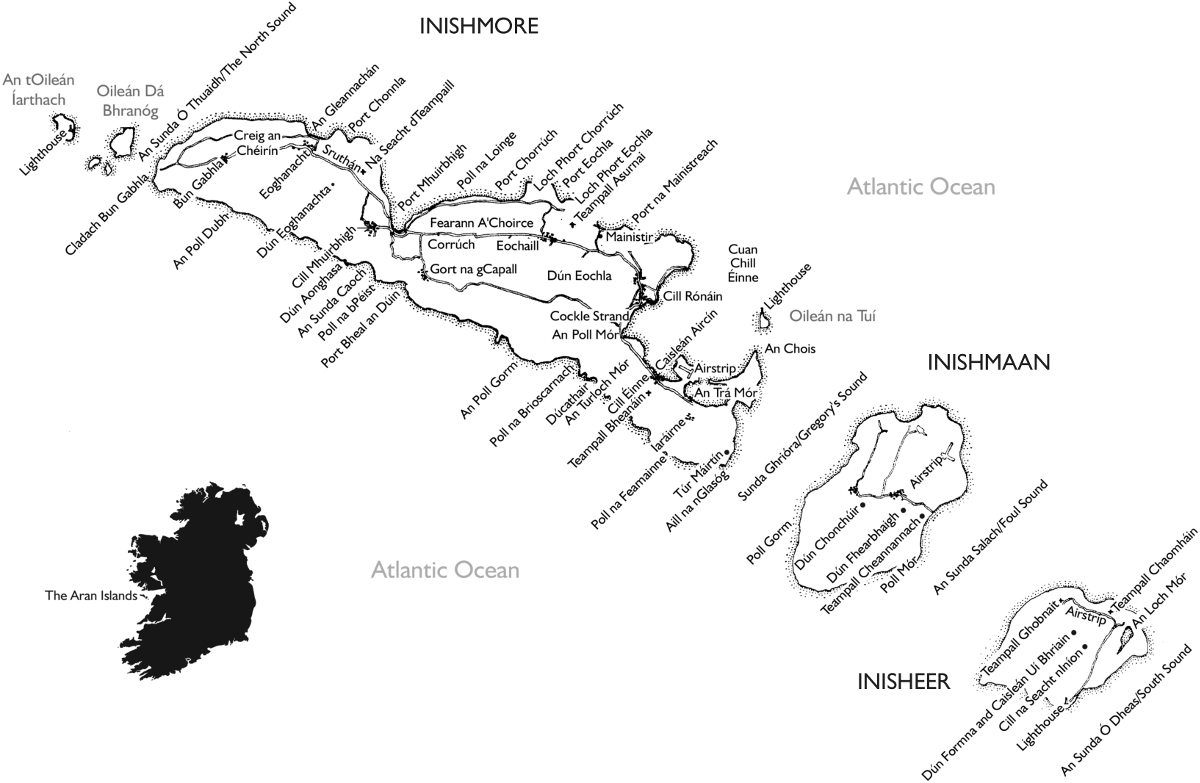

The three main islands, Inishmore, Inishmaan and Inisheer, are long and low, resembling a group of stranded whales, and together they extend over twenty-five kilometres in an almost perfectly straight line across the mouth of Galway Bay. About 1,250 people live on the islands, but in the summer season visitors swell the numbers considerably.

The Aran Islands are a native Gaeltacht, in which the Irish language is the predominant vernacular or language of the home. The name Aran may have been derived from the Irish word ara, which means kidney, because of the kidney shape of Inishmore. It equally may have been abbreviated from the Irish expression ard-thuinn, meaning the height of the waves. According to legend, the islands are the remnants of a rock barrier that once stretched from Galway to Clare, trapping the waters of the present Galway Bay in a gigantic lake. All three islands are alike in their rock base and also similar to the nearby Burren on the north Clare mainland.

Inisheer (Inis Orr: the Eastern Island) is the nearest to County Clare, lying just under ten kilometres north-west of Doolin. It is the smallest of Arans three main islands, almost square in shape, with an area of ten square kilometres. The broad sweep of the South Sound isolates Inisheer from the mainland, and boats cross regularly from Doolin.

Inishmaan (Inis Mein: the Middle Island) is the next along, separated from Inisheer by three kilometres of water known as Foul Sound. On the other side, it is separated from Inishmore by two kilometres of open sea known as Gregorys Sound, named after a revered hermit saint, Gregory of the Golden Mouth, who is reputed to have lived and died on Inishmaan. It is much smaller than Inishmore and more compact in shape, extending just five kilometres from east to west.

The wind-swept cliffs of Inishmore, the largest Aran island.

Inishmore (Inis Mr: the Big Island) lies nearest to the Galway mainland and is the largest and best-known island. It is regarded as the capital of the Aran Islands. The sheltered harbour at Kilronan (Cill Rnin) has long been the main entry point for visitors to Aran. The islands inhabitants occupy an area amounting to little more than thirty-one kilometres. The bay of Killeany (Cill inne) forms a natural waist to the island. From there, Inishmore rises north-westward and achieves its greatest width before descending to the narrow neck at Port Murvey (Port Mhuirbhigh), less than a kilometre wide. A second, slightly lower ridge rises to the west of this bay, widening the island once more before it slopes gently down to the Atlantic at its north-western tip.

A patchwork of small fields on Inishmaan.

Other small, uninhabited islands complete the Aran group: Rock Island and Straw Island, both home to lighthouses; and Brannock Island (Oilen d Bhrang: the island of the two small ravens).

Nowadays, the Aran Islands are easily accessible by sea and air. Ferries run from Doolin in County Clare (seasonal) and Rossaveal in County Galway (all year round). Aer Arann Islands operates flights from Inverin in Galway to all three islands. But in times past, isolation was a feature of Aran life. Gale-force winds still occasionally sever shipping links, and back when this was the only form of transport, the population would have been cut off from the outside world, often for weeks on end. The shelving sea bed around the islands makes for a particularly treacherous sea during a storm the waves break more than a kilometre from the shore, sending gigantic white combers rushing towards the rocks. Communications were then cut off, mail and visitors failed to arrive, and supplies of food ran low the community had to rely on its own resources. If one of the inhabitants fell ill during storm conditions and needed hospitalisation, sometimes a crossing had to be attempted. The islanders grimly joked that a patient, in his terror, forgot about his illness until he reached the safety of Rossaveal on the mainland, where his condition immediately deteriorated once more!

Traditional currachs.

The Naomh anna ferry sailed for thirty years between Galway and the Aran Islands, before it was taken out of action in 1986.

T HE J OURNEY TO A RAN IN THE N INETEENTH AND E ARLY T WENTIETH C ENTURIES

In those years, travel to the islands was usually undertaken in the traditional currach (pr: cur-rock) or curragh, a boat made of skin fixed over a wooden frame, thus giving a light but fragile vessel that pitched and tossed with the high waves. What was it like to travel out to Aran this way? Here we have a description from John Millington Synge, the famous playwright, who visited Aran every summer from 1898 to 1902, living with families on Inishmore and Inishmaan. His book The Aran Islands is an account of life in that era.

We set off. It was a four-oared curragh, and I was given the last seat so as to leave the stern for the man who was steering with an oar, worked at right angles to the others by an extra thole-pin in the stern gunnel.

![Greek islands [2018]](/uploads/posts/book/209249/thumbs/greek-islands-2018.jpg)