All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Islands of New Brunswick : lives at low tide / Allison Mitcham.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued also in print format.

1. Islands--New BrunswickHistory. 2. New BrunswickHistory. I. Title.

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the research council of the Universit de Moncton for assistance given in research for this book.

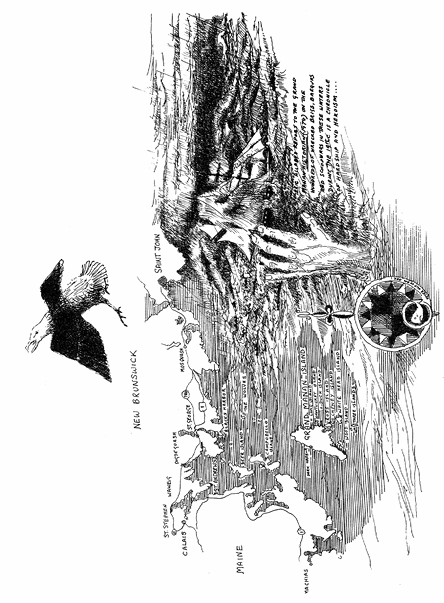

In addition, I wish to thank the following people for their information and moral support: Chief and Mrs. Peter Barlow, Mr. and Mrs. Wainwright Weston, Father Charles Mercereau, Marvin Snowdon, Noel and Jean Justason, Bernard Holt, the Saint Andrews Historical Society; my editor at Nimbus Publishing, Whitney Moran; my daughter, Stephanie, who accompanied me to many of these offshore islands and who has long been my most helpful support and critic for my books; and my husband, Peter, for his lovely illustrations.

Introduction

L ike ships, small islands are fascinatingand for many of the same reasons. Surrounded by water and cut off from conventional society on the mainland, life is strictly governed by storms and tides as well as by the unavoidable interactions of human beings confined to a limited space. On a ship as on an island, it is virtually impossible to avoid close contact with the others who live there too; and so, as countless writers of sea stories have shown, this makes for different sorts of relationships between individuals. Depending on circumstances, both tolerance and hostility have a deeper hold on ships and islands than on the mainland, where individuals are freer to come and go independently of their neighbours. After all, one can just as easily leave some of our offshore islands in a storm or fog or shifting ice as one can put out from an ocean liner in the mid-Atlantic. Because of this, dramas at sea and on islands develop, whereas on land the tensions causing them are more apt to be diffused.

A good example of explosive tension resulting in a dramatic series of events occurred early in the nineteenth century on Grand Manan, when Mr. Wilfred Fisher, nicknamed Th e Emperor of Grand Manan, took the law into his own hands because he felt that his power was threatened. Like the captain of a ship, he apparently demanded a sort of absolute allegiance from the islandersan allegiance unthinkable on the mainland. Like a power-mad captain in a Melville novel, Mr. Fisher set out to demonstrate his authority, convinced that he was the law. ( Th e events leading up to Mr. Fishers actions and the outcome are discussed in the chapter on Grand Manan.)

Drama is also triggered on both ships and islands by accidents and emergencies that can be more easily dealt with on the mainland because of access to special equipment and personnel. Fires, storms, sudden and severe illnesses, accidentsthese all seem more traumatic occurrences at sea than on the mainland. At the same time, such events also call for the sort of hardiness and individual initiative that is less often needed on the mainland.

For these reasons, islands and ships are particularly rich sources of folklore. Th ere is a mystique surrounding bothan aura of romance, mystery, and adventure. Tales of ghosts, pirates, treasure, strange and inexplicable happenings, heroism, and disaster hover with the persistence of seagulls. Th ere is a uniqueness to each boat and island. Aside from obviously having certain basics in common, any long-time sailor or islander would be quick to dispel a mainlanders contention that any one ship or island is much like another; they are individual, manned by crews of very different sorts.

Th e islands off the coasts of and New Brunswick that are represented in this book have been selected because they are so different from one another, and because each is so special in its own way. Th e islands vary in size, geographical settings, topography, the ethnic and religious backgrounds of their inhabitants, and in historical, ecological, aesthetic, and commercial significance. Although all have at one time been connected with fishing, each has other associations. Some are important as bird nesting grounds; others have so strongly grasped the imagination of visitors that they have been the settings of novels and poems; and most are associated with exceptional individualssome internationally famous, others well-known in Atlantic Canada, and still others who remained unknown before the appearance of this book. Finally, the connection of each of these islands to the nearby mainland is, to some extent, important here. Th ere are also links among the islandsthe Fundy and Northumberland Strait islands for instance. Yet, while recognizing the regional similarities that certain islands share, it is nevertheless the uniqueness of each island that remains the dominant and lasting impression.

Grand Manan

The name MANAN, of Grand and Petit Manan, is certainly of Maliseet-Passamaquoddy-Penobscot Indian origin, and means simply THE ISLAND, the prefixes having been added by the French to distinguish the two.

W. F. Ganong, Th e Origin and History of the Name Grand Manan

F or the Loyalist settlers and their descendants, as for the Aboriginal people before them, Grand Manan has always been the island dominating its own archipelago as well as much of the rest of the Bay of Fundy. Whatever the difficulties of living hereand there are many (the icy water, the dangerous shoals and currents surrounding the island, the fierce gales, the dense fogs, and the almost two-hour ferry crossing from the New Brunswick mainland)Mananers seem to almost unanimously agree that their island is the best place in the world to live.

Part of the reason for this attitude is the success of the islands fisheries, which are among the worlds most flourishing. Th e extreme coldness of the water, the high tides and dangerous eddies, the shoals and ledgesall seem to provide just the kind of environment that the fish crave. Catches off the island have been legendary, so it is almost impossible to impress a Mananer with a fish storyhe is sure to be able to top it. If you do not believe him, he may refer you to a statistical reportalthough not necessarily a contemporary oneto back him up. Here is one such account taken from Th e Perley Report on the Fisheries of Grand Manan (1850):