Maura Scannell of the National Botanic Gardens, Conor Mac-Dermot of the Geological Survey, Professor Etienne Rynne and Dr. John Waddell of the Archaeological Department, UCG, Professor T. S. Mille, Dr. Angela Burke of Roinn na Nua-Ghaeilge , UCD, and the library staff of UCGto these and to many others who backed me with learning, and to the several hundred Aran men, women and children who shared their lore with me, I owe the possibility of this book.

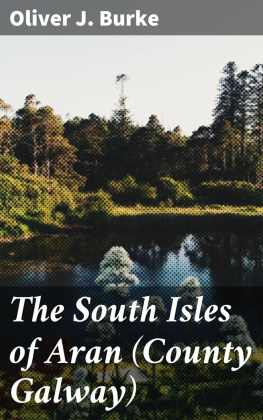

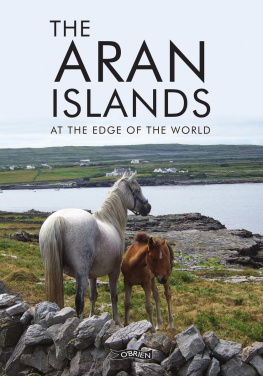

In County Clare on the west coast of Ireland, between the granite of Galway and the sandstone of Liscannor, rises a vast limestone escarpmentpewter in color on a dull day, and silver in sunshine. The limestone begins in the area of Clare known as the Burren, from the Gaelic boireann, meaning rocky place. It extends in a northwesterly direction, dipping beneath the Atlantic, to resurge thirty miles offshore as three islands: rainn, Inis Mein, and Inis Orror the Aran Islands, as they are also called.

Limestone has been blessed with two exceptional English writers . The first of these is W. H. Auden, who loved the high karst shires of Englands Pennines. What most moved Auden about limestone was the way it eroded. Limestone is soluble in water, which means that any weaknesses in the original rock get slowly deepened by a process of liquid wear. Thus the form into which limestone grows over time is determined by its first flaws. For Auden, this was a human as well as a mineral quality: he found in limestone a version of the truth that we are defined by our faults as much as by our substance.

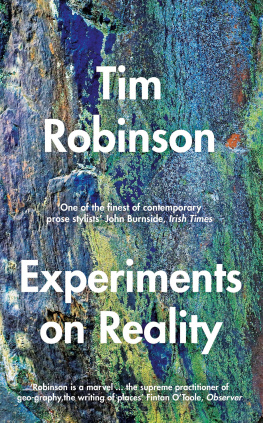

The second of the great limestone writers is Tim Robinson. In the summer of 1972, Robinson and his wifeto whom he refers in his writing only as Mmoved from London to Aran, the largest of the islands. Their first winter was difficult: big Atlantic storms, brief days, and an unprecedented sequence of deaths [among the islanders], mainly by drowning or by falls and exposure on the crags, all challenged their resolve to continue living there. But they did stay, and Robinsona mathematician by training and an artist by vocationbegan to consider how he might respond creatively to his adopted landscape.

So began one of the most sustained, intensive, and imaginative studies of a place that has ever been carried out. Robinson conceived of a local epic: a two-volume prose study of Aran, accompanied by a new map of all three islands (which he would survey and draw). He decided that he would not write a diary of intoxication about Aran, for enough of these already existed, penned by J. M. Synge, W. B. Yeats, and Lady Gregory among others. Instead the first volume, Pilgrimage, would describe a circumambulation of the islands coast. Robinson would walk the coastline clockwise, sunwisethe circuit that blessesand he would walk not at a penitential trudge but at an inquiring, digressive and wondering pace. The features of the coast would be the stations of this offbeat pilgrimage, and close attention would be its method of devotion. The landscape itself would improvise the narrative. Once this ritual beating of the islands bounds was completed, he would then delve into Arans intricate interior for the second volume, Labyrinth.

Long before psycho-geography became a modish term, Robinson was out on the drive: walking the rimrock, surveying, measuring, talking to the custodians of local lore, watching, dreaming, and recording. In bad weatherof which there is plenty on Aranhe would hold his notebook and pencil inside a clear plastic bag, tied shut at his wrists, and proceed in this manner . He must have looked, to those who encountered him, like a deranged dowser or pilgrim, wandering through the mists and the storm spray, hands locked together in mania or prayer.

For years, Robinson walked, and as he did the sentences began to come: beautiful, dense, paced. Pilgrimage was published in 1986, fourteen years after his arrival on Aran. As with all great landscape works (of which there are very few), it is at once territorially specific and utterly mythic. The one island becomes in Robinsons view both a fragment of broken, blessed, Pangaea (a version of the world on which we all live, and whose materiality we differently adore and resist) and also a terrain with its own intricate and indigenous histories. He wanted, as he put it, to remain attentive to the subtle actualities of Aran life, but also to the immensities in which this little place is wrapped. This continual vibration between the particular and the universal is one of the books most distinctive actions.

The opening chapter, Timescape with Signpost, offers a creation myth for Aran: its geological birth out of the ur-continent of Pangaea and from its unbounded encircling ocean was Panthalassa , all-sea. The writing here is fabulous in the old sense of that word: a localized version of Genesis, in which can distantly be heard the thunder of Old Testament rhythms. It places Aran and its people in the context of what John McPhee has called deep time: the geological perspective of past and future that can make human presence, all our lore and our nightmares, seem irrelevant. Unless vaster earth-processes intervene, writes Robinson, Aran will ultimately dwindle to a little reef and disappear . It seems unlikely that any creatures we would recognize as our descendants will be here to chart that rock in whatever shape of sea succeeds to Galway Bay. Such timescales make a nonsense of most human behavior and all human prejudicesespecially that of nationalism. The idea that you can belong to a defined area of land, or even that a defined area of land can belong to you? Lunacy, says Robinson. Seen within the perspective of deep time, the geographies over which we are so suicidally passionate are fleeting expressions of the earths face.

But after this opening vision of immensity, Robinson focuses tightly down upon Arans actualities: the habits of its birds, animals , and plants; its present human customs and pasts. Aran has been inhabited for more than four thousand years, and such prolonged human activity on such a limited area of land means that history exists thickly there. Each era has left its marks, usually in the form of stone (a substance that may fall, but still endures): cairns, walls, tombs, cashels, megaliths, cells, chapels Robinson treats each of these structures as a historical puzzle, whose origins and name mightwith luck and diligencebe fathomed.

He brings this fierce curiosity to bear on all the phenomena that he encounters on his pilgrimage. How was the storm beach of Gort na gCapall formed? Why does the wren flourish on one side of Aran, and the raven on the other? Why is Cockle Strand so called? How were the puffins of Poll an Iomair, the trough-like cliff, harvested? What ceremonies surrounded the firing of the kelp kiln of Mainistir? Robinson investigates these questions, and thousands more. He is interested, to borrow a phrase from Les Murray, in only everything. Reading Pilgrimage, you are astonished at the density of the cultural strata that have settled over this landscape, and at the care and precision with which Robinson excavates them.

Many landscape writers have striven to give their prose the characteristics of the terrain they are describing. Few have succeeded as fully as Robinson. The erosive habits of limestone means that it is rich with clandestine places: runnels, crevasses, hollows, and gulleys. So too is Robinsons style, the polished surfaces of which contain an enormous complexity of thought. Like limestone , his books are broken up into irregular sections. Chapters is not quite the word for these sections: better, perhaps, to call them blocks, or even clintsthe exact term for the surface of a weathered slab of limestone.