CONTENTS

To our mothers, Evelyn Rueb and Kerstin Schweizer, who have taught us much;

and to our children, Jack and Hannah, from whom we continue to learn

INTRODUCTION

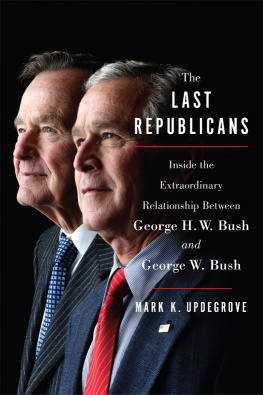

On election night, November 1994, governor-elect George W. was beaming in his hotel suite in Houston. Fourteen hundred miles to the east, younger brother Jeb was sitting dejectedly in his hotel suite in Miami.

Both men had decided to run for governor of their respective states of Texas and Florida in January 1993. They had not really consulted each other or coordinated their plans. Maybe the Kennedys handle this part of the job better than we do, Jeb Bush noted, but it's just too complicated.

Conventional wisdom in the family had it that Jebbie would win and W. would go down in defeat. Jebbie was, after all, the serious one, the one who had been meticulously planning to run for office for more than a decade, the one who really knew his stuff, and the one who would drop everything whenever his father needed him. He actually read those briefing papers put out by the think tanks in Washington and had headed up the local Republican Committee in Miami. And, if he won the governorship, he would probably run for president in 2000.

And his older brother? Well, W. was smart and shrewd. But he was also the rebel, edgy and unpredictable. His mother, Barbara, thought that his running for governor was a big mistake and had told her eldest son precisely that. Governor Ann Richards would likely come up with something during the campaign to set him off, and he would probably lose and lose big. Only a few years earlier, when a family history was being written, Marvin Bush, a younger brother, had described his oldest sibling as the family clown.

But on that election night, when the tallies came in, the results were stunning to most in the family. Jeb was going down to defeat in Florida and W. was beating Ann Richards big. When W. was finally over the top and Richards had conceded, he got a phone call in his hotel suite; it was his father.

Aunt Nancy Ellis was standing nearby as W. chatted with his dad. When he hung up the phone, a disappointed W. simply shook his head. Almost the entire conversation had apparently been about Jeb's loss, with barely a mention of his win. His aunt listened as he said, Why do you feel bad about Jeb? Why don't you feel good about me?

A little more than six years later, 274 members of the extended Bush family converged on the nation's capital. Washington, D.C., was cold and dreary. But that didn't matter to the group of Bushes, Walkers, Clements, Houses, and Ellises that had arrived from eighteen different states. They were there, after all, to help coronate the second member of the Bush clan to be elected president (Two and counting... cracked one of the young cousins).

The backgrounds of those family members covered a broad spectrumyoung and old, Easterner and Midwesterner, partisan and apolitical, conservative and liberal. Some were staying in a large bloc of rooms at the elegant Jefferson Hotel while others were in the Marriott downtown, and buses had been hired to take them from venue to venue. This event was part inauguration, part family reunion. Former president George Herbert Walker Bush (41 in the lexicon of the family) was making the rounds as he always did, graciously trying to greet everyone. On Thursday evening he met with his sister, Nancy Bush Ellis, and his brothers Bucky, Pres, Jr., and Johnny, to reminisce. They talked about the pending tenure of George W. Bush and swapped family gossip. But as they always do, they also talked about the past. They laughed quite a bit, but they all kept tearing up.

Two days later, many of them stood on the podium of the West Lawn of the Capitol Building as George W. Bush took the oath of office. The remarkable rise of the eldest son, the rebel, was now complete. The family's political fortunes, expected to be carried by Jeb, were instead now on his older brother's shoulders. As in all things, it's always good to be the winner, said cousin John Ellis. So they saddled up with ol' George W.

Tears welled up in the eyes of both George Bushes. On his wrists, the new president wore the cufflinks that his grandfather had worn in the Senate and that his father had worn in the White House. It is remarkable to think that had the electoral fortunes been in Jeb's favor in 1994, a Bush still might have been sworn in as president, only the first name would be different.

When the Bushes gathered in Kennebunkport, Maine, a few months later, the elder George Bush relinquished his seat at the head of the family table; that spot would now go to his eldest son. During the next several years, some of the most eventful in American history, W. would consult with his father regularly. Sometimes they would agree; at other times, over issues such as the war in Iraq, they would express differences. And as President George W. Bush conducted the affairs of the country, he would find himself at times dealing with foreign heads of state or international players in the Middle East and Asia who had business dealings with his family.

For more than a century the Bushes have been at or near the center of America's public lifeas friends of presidents, captains of industry, capitalists, senators, congressmen, ambassadors, governors, federal judges, and two American presidents. While the Bushes lack the flamboyance of the Roosevelts or the enormous wealth of the Kennedys, they have surpassed those two great dynasties. There can be little question that the Bushes are now the most successful political family in American history. Yet precious little has been written about the Bushes in contrast to the hundreds of books about the Roosevelts and Kennedys.

Biographies have been written about both former president Bush and President George W. Bush, but details about the larger family are scant. To the extent that the family has been studied at all, it has emerged as a caricature. New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd has compared the Bushes with a sinister Mafia clan while at the same time declaring that they are a boring group of cutouts from a Brooks Brothers catalog. Michael Kinsley claims that he can find nothing serious about them. They are motivated, he claims, by a preppy ethic that one should be serious about games and casual about life. Journalist Evan Thomas of Newsweek is equally unimpressed. The Kennedys flew too close to the sun. The Bushes just ask for more pork rinds.

Why the caricature? Mystery often invites these kinds of labels. Unlike the Kennedys and even to some extent the Roosevelts, the Bushes have been famously disinterested over the years in speaking to the media about their family and the dynamics within the greater Bush clan. Time magazine has accurately dubbed them the Quiet Dynasty because they have quietly gone about their business, flying below much of the media radar.

Inside the family there is an unwritten code about dealing with the media, a code that is firmly enforced. There is an inner circle in the family, Bush cousin John Ellis explained. If you haven't said anything bad to the press, you're in pretty good shape. But if you said anything bad, Barbara [Bush] kind of puts you in the deep freeze for a while. And then you have to work your way out. I think you could burn down the house in Kennebunkport and you'd be in less trouble than if you gave a bad quote to the New York Times.

The family's distrust and at times disdain for the media has deep roots, running back some fifty years to when Prescott Bush was making his first bid for the U.S. Senate. That distrust runs particularly strong when it comes to writing about family matters.

Next page