Dedication

For my very own Elinor (Ellie)

The room was most dear to her, and she would not have changed its furniture for the handsomest in the house, though what had been originally plain, had suffered all the ill-usage of children and its greatest elegancies and ornaments were a faded footstool of Julias work, too ill done for the drawing-room, three transparencies, made in a rage for transparencies, for the three lower panes of one window, where Tintern Abbey held its station between a cave in Italy, and a moonlight lake in Cumberland; a collection of family profiles, thought unworthy of being anywhere else, over the mantelpiece, and by their side, and pinned against the wall, a small sketch of a ship sent four years ago from the Mediterranean by William, with H.M.S. Antwerp at the bottom, in letters as tall as the main-mast.

Mansfield Park , VOL 1, CH. 16

[S]he seized the scrap of paper locked it up with the chain, as the dearest part of the gift. It was the only thing approaching to a letter which she had ever received from him; she might never receive another; it was impossible that she ever should receive another so perfectly gratifying in the occasion and the style. Two lines more prized had never fallen from the pen of the most distinguished author never more completely blessed the researches of the fondest biographer. The enthusiasm of a womans love is even beyond the biographers.

Mansfield Park , VOL 2, CH . 9

CONTENTS

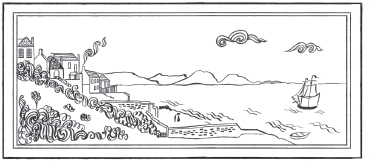

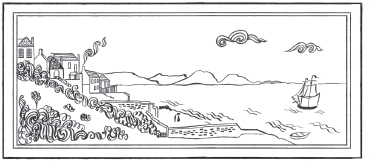

This is a watercolour of Lyme Regis on the southern coast of England. The cottages nestle on the hillside. An old stone breakwater leads down to the shoreline. A man and a woman are walking on the beach and a solitary figure is looking out to sea. A rowing boat is on its way out to a ship at anchor in the bay. The eye is drawn to an expansive view of sloping cliffs and open sky.

Jane Austen loved the sea. The story goes that when her father announced in December 1800 that he was leaving his position as rector of the parish of Steventon and retiring to Bath, she was so shocked that she fainted. She reconciled herself to the move only when the family promised to take a holiday by the seaside every summer. In 1801 and 1802 they went to Sidmouth and Teignmouth in Devon. In 1803 and 1804 it was the turn of Lyme Regis.

The young people were all wild to see Lyme. When they arrive, in chapter eleven of Persuasion , Jane Austen describes the little seaside resort in the style of a tour guide: the pleasant bay, the new-fangled bathing machines, the famous Cobb, the beautiful line of cliffs stretching out to the east of the town, the charms of the immediate environs the high sweep of countryside around Charmouth, the woody varieties of the cheerful village of Up Lyme, and, above all, Pinny, with its green chasms between romantic rocks a scene so wonderful and so lovely is exhibited, as may more than equal any of the resembling scenes of the far-famed Isle of Wight.

These places must be visited, and visited again to make the worth of Lyme understood, Jane Austen tells her readers. She had visited Lyme at least twice, on one occasion witnessing a fire that destroyed a number of houses. When she describes the place in her novel, she is visiting it yet again, this time in her imagination. Her description is the literary equivalent of the engravings of popular tourist sites that were readily obtainable in the burgeoning print market of the age the Regency version of the picture postcard.

Jane Austen cared a great deal about accuracy. She wanted her novels to be true to life. When reading a draft of a novel by her niece Anna, she pointed out that it was an error to portray people in Dawlish gossiping about the news from Lyme: Lyme will not do. Lyme is towards 40 miles distance from Dawlish and would not be talked of there. Her novels were grounded in the real world. In order to create them, she drew upon the reality that she knew: the people, the places, the events. The celebrated fictional scene in which Louisa Musgrove nearly dies when being jumped off the narrow steps of the Cobb is not based on a real incident, but it could not have been written if Jane Austen had not visited the real Lyme and memorized its topography.

The picturesque description of the romantic rocks of Lyme is not, however, her most common style. And in this case her passion for the sea perhaps led her to idealize the reality of the place. I was disappointed in Lime, wrote her sister-in-law Mary to that niece Anna, as from your Aunt Janes Novel I had expected it a clean pretty place, whereas it was dirty and ugly.

The fall on the Cobb, the bad-tempered exchange at Box Hill, the escape across the ha-ha from the grounds of Sotherton, the road-traffic accident with which her final unfinished novel begins: outdoor scenes in Austens novels are often dramatic excursions involving misadventures, transgressions, arguments, misunderstandings, proposals whereas her habitual location is indoors, within the world of polite, if barbed, conversation in drawing rooms and over dinner tables. Chapter eleven of Persuasion does not dwell for long on the seaside panorama. The narrative swiftly follows the visitors inside.

Not, however, into a great house of the kind that has become familiar in television and film adaptations of Austens novels (in which the houses are nearly always bigger than they should be). Near the foot of an old pier of uncertain date on the seafront at Lyme there is a row of cottages. We enter a cramped but welcoming parlour. It is the home of Captain Harville, who has retired in poor health as the result of a severe wound incurred on naval service during the war that lasted for almost the whole of Jane Austens adult life. This snug little dwelling-place will be revisited later, but for a first glimpse of Austens art of minute observation consider a single detail:

Captain Harville was no reader; but he had contrived excellent accommodations, and fashioned very pretty shelves, for a tolerable collection of well-bound volumes, the property of Captain Benwick. His lameness prevented him from taking much exercise; but a mind of usefulness and ingenuity seemed to furnish him with constant employment within. He drew, he varnished, he carpentered, he glued; he made toys for the children, he fashioned new netting-needles and pins with improvements; and if every thing else was done, sat down with his large fishing-net at one corner of the room.

Anne Elliot will soon engage Captain Benwick in conversation about books, debating the relative merits of the two most fashionable poets of the day, Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron. She gently suggests that romantic poetry might not be the most healthy reading for a man with a broken heart such as Benwick though she sees the irony of her admonitions to patience and resignation in the light of her own broken heart.

But it is Captain Harvilles carpentry that sticks in the mind: the prettily fashioned shelves, the varnish, the glue, the toys for the children. Jane Austen grew up in a house of books and reading, but she also came from a family that valued handiwork, the craft of making things, whether with needle or wood.

Captain Benwick reading poetry aloud while Captain Harville mends his net is a little image of how she imagined a secure home and a sense of belonging. Her family circle was a place of quick tongues, laughter and moving fingers, with a novel being read aloud and everyone busy at their needlework. Both her world and her novels can be brought alive through the texture of things, the life of objects.

Next page