On Hitlers Mountain

OVERCOMING THE LEGACY OF A NAZI CHILDHOOD

IRMGARD A. HUNT

TO MY CHILDREN,

PETER AND INGRID

Contents

A SENSE OF GREAT URGENCY, AFTER YEARS OF postponement, propelled me to write this memoir. With the passing of my parents generation many facts of everyday life under the Nazis and the German peoples feelings about the Nazi experience are already lost forever. Firsthand accounts by the average, law-abiding, middle-class German who helped sweep Hitler to power and then supported him to the end are becoming a rarity. Yet the seemingly petty details of these peoples lives are actually often symbolic and always telling. They illuminate the societal transitions from pre-Nazi, to Nazi, to post-Nazi, and from a postWorld War I to a postWorld War II mind-set. In the continuing struggle to understand the pastboth personally and as a lesson from historythese details are too important not to be recorded and thus preserved.

Of course historians have written countless volumes documenting and analyzing Hitler and the Third Reich. Biographers, survivors, perpetrators, diarists in hiding, and novelists have presented the stories of Nazi criminals and power brokers; famous scientists and artists who either went along or were killed or forced into exile; politicians and military leaders of the era; and, powerfully so, the victims of the Holocaust and all others who suffered the horrors of the concentration camps. Yet even now, when enough distance from these events allows and even welcomes accounts of the Nazi era and the war from the German perspective, little has emerged about the daily lives of German families who considered themselves moral, honorable, and hardworking and whose adult members expected to live decent, respectable lives. It was those adults, those ordinary citizens, who most wanted to forget the past once the Nazi years were over and who preferred not to recall their participation in the Third Reich.

It was left to the next generationmy ownto seek to discover what people thought, knew, and chose to do and how it was possible for Hitler to receive their silent cooperation and often enthusiastic support. A universal answer may never be found, but perhaps an examination of just one family, mine, can provide additional understanding of what paved the way to Hitlers success and led to wholesale disaster.

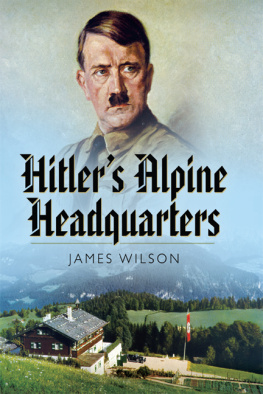

I grew up in the beautiful mountains and villages of Berchtesgadena wide, multibranched valley located in a part of Bavaria that juts like a thumb into the Austrian Alps. I was born there in 1934, a year after my parents had voted for Hitler and he had assumed power. Hitler had chosen Obersalzberg, a hamlet above Berchtesgaden, as his home and headquarters. His presence on that mountain stamped my early years with a uniqueness that could not be claimed by other middle-class children elsewhere in Germany. The mountain loomed large over every aspect of my childhood in this highly visible and public place, in the shadow of the Eagles Nest and near the lair of men whom the world would come to view as monsters.

How does one remember early childhood events? Once I began the task of thinking back, I realized that my childhood memories have to a great degree remained vividly and indelibly imprinted on my mind. I was a very curious, somewhat critical child, and according to my aunt, I had a precocious talent for eavesdropping and spying. For lack of entertaining or varied media offerings and other diversions, the people of Berchtesgaden, including my family and friends, thrived on local gossip, word-of-mouth news, and repeatedly told tales. The grown-ups talked and I listened, building a reservoir of recalled stories, rumors, and commentary about all that came to pass in my town during the years of Nazi rule. Until it was quietly buried in 1945, the account of my meeting with Adolf Hitler was so much a part of our family lore that I committed every detail to memory even though I was only three and a half years old when the incident occurred. Since this is not a history but a memoir, my personal perceptions and hindsight have of course been allowed to color the happenings. Nonetheless, these impressions and perceptions that inevitably reshape memory give an accurate picture of the essence, the mood, the impact of any given event during those years.

This memoir is as much the story of my mother and my grand-parentsall passed awayas it is my own. Many details from their lives and my babyhood came from Tante Emilie, ever cheerful, lucid, and full of memories at age ninety-six. During recent visits in Berchtesgaden, still home and summer home to my two sisters, I was greatly aided by long, frank conversations with them, their families, and friends whom I have known since my youth and who provided confirmations and a wealth of details. Old friends walked the old trails and the Obersalzbergstrasse with me, passing houses and cottages where we lived and played and whereunrecognizably nowthe Nazi elite and the S.S. had held sway.

Thanks to my sisters and my cousins in Selb, I had access to family documents, marriage manuals, genealogical information required by the Nazis, my fathers military records, letters from my Phlmann grandmother to her soldier husband written during World War I in the neat, steep, spiky German script that she had learned in grade school and had not practiced much since. To look at these letters was to hear the scratching of her steel pen on the lined, white pad of paper, to know from the darker script where she paused to dip her pen again into the black inkwell on the wobbly kitchen table, to sense her pauses and her hurry to finish and return to her endless chores. In addition, family photographs and documents from my mothers cupboard drawers were unearthed. They included the diary she kept during World War II, which, though terse, portrays the feelings and daily struggles of an average German woman, widowed and alone with her children, and touches on the major events of those years. The small accounting booklet she kept for eight years19301937paints a poignant picture of an utterly frugal life in which every pfennig was counted and tracked.

Throughout his years in power Hitler had remained enamored of Berchtesgaden and made some of his most momentous decisions, such as the pact with Stalin in 1939, on Obersalzberg. It was here that he received Chamberlain, Mussolini, and even the duke of Windsor and his American wife, Wallis Warfield Simpson. The conquest of Obersalzberg and the hoisting of the American flag by the 101st Airborne Division on the mountain were a fitting, symbolic ending to the war and the Third Reich.

Once the war ended and we were recovering from its anxieties and privations, we slowly began to realize to what degree the Nazis had shaped our minds and every detail of our daily lives, and the enormity of German guilt. I also began to appreciate those people, like my grandfather, who had expressed doubts, who had dared to be critical, and who, though basically powerless, had made brave attempts at resistance. They made a huge difference in my readiness to welcome the end of Hitlers reign and embrace new values despite the sadness over our many sacrifices and losses. Even then I made up my mind always to be on the lookout for the signshowever insidious and seemingly harmlessof dictatorships in the making and to resist politics that are exclusive, intolerant, or based on ideological zealotry and that demand unquestioned faith in one leader and a flag. I hope that young people everywhere learn to recognize the danger signs and join me in the mission to prevent a recurrence of one of historys most tragic chapters.

ON HITLERS KNEE

OCTOBER 1937

A shout went up and the crowd pushed forward. I grabbed my mothers hand and stood frozen, waiting. Then she said, There is Adolf Hitler! Indeed, here he was, outside his big rustic villa, the Berghof, walking among us and shaking hands, looking jovial and relaxed. He strode in our direction, and when he saw me, the perfect picture of a little German girl with blond braids and blue eyes, dressed for a warm fall day in a blue dirndl dress patterned with white hearts under a white pinafore, he crouched down, waved to me, and said, Komm nur her, mein Boppele (Come here, my little doll). Suddenly I felt scared and shy. I hid behind my mothers skirt until she coaxed me firmly to approach him. He pulled me onto his knee while his photographer prepared to take pictures. The strange man with the sharp, hypnotic eyes and dark mustache held me stiffly, not at all like my father would have, and I wanted to cry and run away. But my parents were waving at me to sit still and smile. Adolf Hitler, the great man they so admired, had singled me out, and in their eyes I was a star. As the crowd applauded, I saw my grandfather turn away and strike the air angrily with his cane.