FASHION IN THE TIME OF JANE AUSTEN

Sarah Jane Downing

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

THE AGE OF ELEGANCE

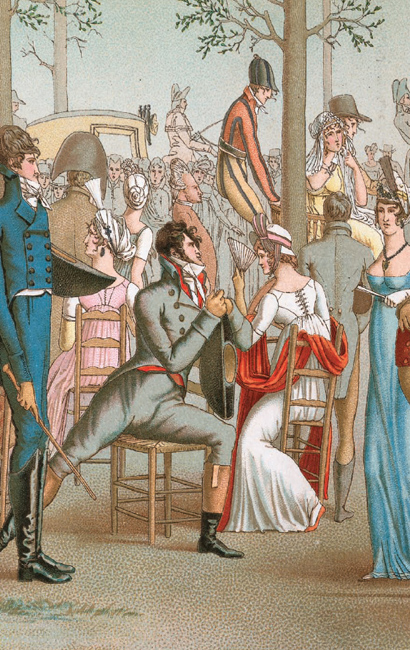

Promenade de Longchamp During Year 10 of the French Consulate [1802] (Auguste Racinet for The Costume History, c. 187688). Polite society was ever more diverse and exciting and this was reflected in an increasing range of styles.

T HE WORLD was on the brink of revolution when Jane Austen was born on 16 December 1775. The battle for American Independence heralded an era marked by decades of war and conflict as the old order was swept away in an explosion of radical ideas and technological innovations. As the modern era loomed on the horizon, propelled by capitalism and industrialisation, fashion became the barometer of change. Looking for the first time beyond the decorative, it embodied the philosophical, the political and the practical issues of the day. For the first time England not only revolutionised style, but with industrialisation it revolutionised the process to produce it.

It was an era of contradiction immortalised by Jane Austen, who adeptly used the newfound diversity of fashion to enliven her characters: Wickhams military splendour, Mr Darcys understated elegance, and Miss Tilneys romantic fixation with white muslin. They are characterised by their dress but rarely do they speak of it; unless they are one of Austens sillier characters, they maintain the good taste and decorum of the times, which held that it was poor manners to impose conversation about such footling matters upon company. It was within her private correspondence with her beloved sister Cassandra that she discussed such fripperies as her plans for new bonnet trimmings and the successful reception received by her black velvet cap.

Jane was essentially of the gentry, very aware of the correct way to behave but not necessarily with an income large enough to make it happen easily. Taste and poise should come naturally to a lady, and it was an indictment of a lack of breeding to be worried about looking correct. The drawing room tensions of fashion and faux pas that she so beautifully illustrated were the furthermost ripples of the revolutions that were changing the world.

The impenetrable class order that had held strong since time immemorial was gradually being breached by a budding generation of increasingly wealthy industrialists, entrepreneurs and merchants who were making their own place in society through their ideas and innovations. Their impact was huge, not only in the foundation of the textiles industry and international trade, but in their eagerness to display their newly gentrified status with all the trappings of a country estate.

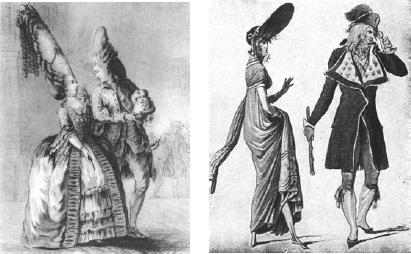

Headdresses (caricature in crayon, c. 1777) in contrast to Les Merveilleuses (c. 1797). There was a radical contrast between the old and new fashions, most notably in the silhouette as the exaggerated confluence of the hoop and the wig were abandoned in favour of a natural slender silhouette.

Fashions had tended to originate at the French Court, transferring to England through royal circles, but throughout the revolutionary years and the Napoleonic wars the typical route for fashions and fabrics coming from France was severed. This coincided with increasing trade with India, which imported fine muslins, cashmere shawls and the raw cotton to be processed by the rapidly growing numbers of mills appearing across the north of England. In France muslins were fashionably democratic for their affordability but in England they were doubly so, as many people became wealthy from cotton and were amongst the first to attain social mobility.

The Advertisement For a Wife (The Third Tour of Dr. Syntax, Rowlandson, c. 1821). There was huge competition for any eligible bachelor so it was essential to be as beautiful and fashionable as possible.

Yorkshire cotton factory child workers, c. 1814. Democratic cottons represented a new egalitarian age for some, but many others lost their independence when they were forced to exchange their cottage industries for the oppressive factory system.

Jane was fourteen in the year the Bastille was stormed marking the beginning of the period of turbulence that would launch democracy as a new force in the world. She had a direct link with the tragedies of the Revolution through her cousin Eliza de Feuillide, who had been married to the Comte de Feuillide before marrying Janes brother in 1797. Eliza was in England in February 1794 when she heard that her husband had met la guillotine, news that would make the horror of the Revolution shockingly real to all the Austen family.

The Anglers Repast (George Morland, c. 1789). Rousseaus ideas about nature became very influential, and as the closest acceptable thing to nature, the English country gentleman unexpectedly found himself a style icon.

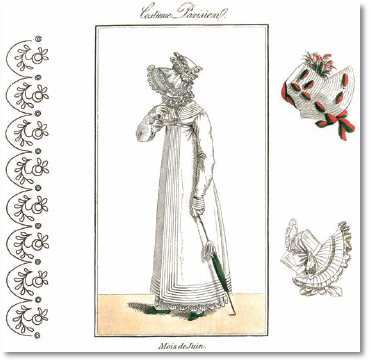

A very rare fashion plate from a dressmakers journal of 1817, giving an embroidery pattern as well as fashions for the upcoming season that would be recreated to order for customers.

Before the Revolution Eliza had enjoyed an illustrious lifestyle in France with the Comte, and frequently wrote to tell her cousins of visiting Marie Antoinette at Trianon, including full details of the queens gowns. Jane enjoyed her keen and witty observations, later using Eliza as inspiration for her novel Lady Susan. Marie Antoinette had a major role in changing fashion away from the tightly corseted ornate gowns with vast skirts over pannier hoops, which she reputedly loathed wearing, to the simpler style langlaise. Rousseaus love affair with the English political system also encouraged the adoption of English fashions, as their studied casualness was regarded as elegantly democratic.

Morning Dresses (The Gallery of Fashion, April 1797). Heideloff was a miniaturist in Paris before the Terror and his beautiful illustrations for The Gallery of Fashion revolutionised the fashion press.

Having been forced to flee from the Terror, many of Paris finest modistes and their clients arrived in London and quickly it became the new fashion capital. Amongst them was Nicolaus Wilhelm Von Heideloff who founded