The past exudes legend: one cant make pure clay of times mud. There is no life that can be recaptured wholly; as it was. Which is to say that all biography is ultimately fiction.

Bernard Malamud, Dubins Lives (1979)

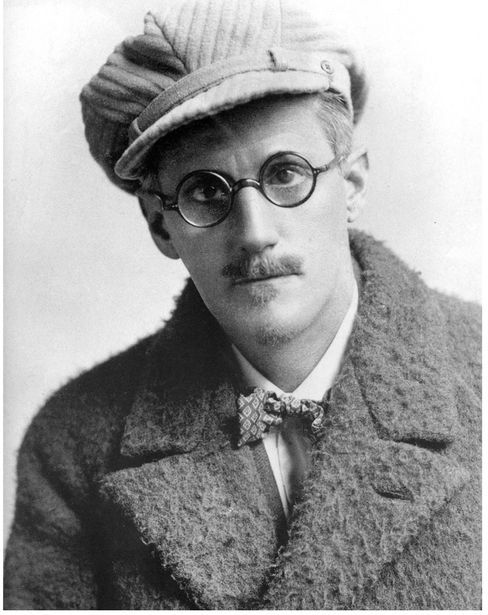

In almost every poll taken in recent years, Ulysses has been acclaimed the greatest novel of the twentieth century. Among critics and intellectuals it is generally regarded as one of the outstanding landmarks of literary modernism, as important, say, as T. S. Eliots The Waste Land, in expressing the experimental and international spirit of post-war Europe in the 1920s. From any point of view, of all the modernists, James Joyce has had probably the most lasting effect on serious fiction. Even so, his impact was not immediate, and Ulysses was still not widely available in unexpurgated form until shortly before his death. However, the slow but certain impact of that book on the wider consciousness is mirrored in the gradual but inexorable progress towards permissiveness in the West. Eliot said Joyce had killed the nineteenth century and Edmund Wilson called him the great poet of a new phase of the human consciousness.

The riverrun of Joyces life was a never-ending escape route into exile of the sort often taken by creative writers in search of a broader vision. His fight against Irish parochial prejudices and Anglo-Irish censoriousness casts him in a heroic light. Under the influence mainly of Ibsen, Zola and Maupassant, he embraced realism, writing fearlessly about the more squalid aspects of human life. And yet his considerable poetic and comic gifts enabled him to lend an aspect of beauty and humour to what many regard as repugnant.

Joyces religious dedication to authorship also picks him out as a writer in the romantic tradition of total commitment, suffering near poverty and financial dependency for much of his life in his determination simply to write. He was fortunate in his sponsors. Certain women (Dora Marsden, Edith McCormick, Harriet Shaw Weaver, Jane Heap, Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier in particular) ensured that he was able to concentrate fully on his great works, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake , and see them published.

From a fading middle-class background, James Joyce, born a Dubliner, became riveted and possessed, even in exile, by the Dublin of his youth. But he needed to escape the suffocating atmosphere of British Ireland and the paralysing grip of Irish Catholicism to find in Europe a milieu in which his art might flourish. That experience fed into his writing a stream of important influences and ideas, but as his reputation grew, he retreated further - into a tight circle of friends and admirers and the strange world of his fiction. This withdrawal, however, only added to his mystery and fame. As war approached or the intellectual climate changed, he moved on - to Paris, Trieste, Zurich, and back to Paris. He escaped one final time - from Vichy France to neutral Switzerland in 1940 - and died shortly afterwards, far removed from most of his friends and remote from his Dublin family, in the obscurity of a Zurich hospital.

Following his death, critics and scholars set out to explore and anatomize the remains of a great life - the progress, the work, and the extraordinary mental landscape. Apart from Shakespeare and the Bible, Joyce has probably spawned one of the most extensive bodies of analytical and interpretive scholarship of all time. Since his death, editions of his work, some well annotated, have continued to appear, the flood of critical tomes and articles has never abated, literary journals have been devoted exclusively to him, and numerous film adaptations, radio and television programmes have featured his life and work.

Joyces fiction is highly autobiographical, but it is also fiction and therefore shaped by the author into a form that served his many purposes in writing and presenting himself to the world as an artist. Dubliners, his first book of fiction, reflects the world in which he grew up - turn-of-the-century Ireland - and many of the characters, whose identities he hardly bothered to disguise, were people known to him. But what his more perceptive early critics noticed was its revolutionary narrative technique, and the unusual economy and bite of his prose. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is both an extended confession and a droll commentary on the young life of Stephen Dedalus, a Catholic schoolboy with intimations of immortality, which, together with Dubliners, can be regarded as portents of the greater works to come.

Ulysses takes the reader for a whole day and nights jaunt seen through the eyes and imagination of an older Stephen and the Jewish Everyman, Leopold Bloom, around the streets of Dublin on 16 June 1904. En route, they encounter a multifarious cast of Joyces acquaintances in a literary free-for-all satirizing a series of styles and genres, closely mimicking the form and spirit of Homers Odyssey and the form and spirit of an old society confronting modernity. With Ulysses, declared Edmund Wilson, Joyce has brought into literature a new and unknown beauty.

Finnegans Wake, his final work, is a tidal wave of teasing verbal conjuration - a dream-like play of voices, the meaning of which is as slippery as the multitude of allusions milling around and interpenetrating the prose. As Joyce himself explained, while Ulysses deals with day and the conscious mind, Finnegans Wake deals with night and the unconscious mind - the single nights sleep of a single if polymorphous character. Although it seems formless and chaotic, it has a strange coherence, a mysterious music, and tells its own hidden story, enriched by great myths and legends. Joyce was, as Wilson has pointed out, the great poet of a new phase of the human consciousness, whose influence has gone deeper than literature. Like D.H. Lawrence, he was aware of the fluidity of human identity, the malleability and unreliability of perceived reality and representations of reality.

To his innovative use of the monologue intrieur (or stream-of-consciousness), Joyce brought a curiosity about the working of his own mind and the minds of those around him. This coincided with the growing interest in Freuds explorations of the human unconscious. And, even though he rejected psychoanalysis, Ulysses in its own way followed the same path, drawing deeply on traditional sources while using the imagination rather than reason as his guide.

But Joyce was not simply a serious-minded experimenter who took the modernist novel to its ultimate conclusion. He was a great and playful satirist with a highly developed comic imagination. Once, asked about Ulysses, he replied, Ive put in so many enigmas and puzzles that itll keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant. Finnegans Wake, he said, no doubt with a hint of irony, was intended as nothing less than a history of the world.

His life was not without its problems, dogged as it was for many years by near poverty, failing eyesight, and the mental illness of his daughter, Lucia. He suffered also the slings and arrows of uncomprehending critics, including some fellow modernists, among them Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf, while Lawrence complained that Ulysses was more disgusting than Casanova. Lawrences disdain was reciprocated, and in 1929, given the opportunity to meet the author of The Rainbow, Joyce refused, calling him a propagandist and a very bad writer.