Contents

: The Murder of Sister Valsa

| The Lust

| The Faith

| The Greed

| The Brutality

| The Friendship

: When You Are at Home

: Falak: The True Story of Indias Baby

| Escape from Bihar

| A New Life Unravels

| The Runaway

| The Battering

| The Circus

| The Radiant Sky

: A Nurses Tribute to BabyFalak

: The Delhi Bus Rape

| The Victim

| A Love Story

| The Suspects

| The Family

| Death in Prison

| Climate of Fear

: Judge Sahib!

About the Publisher

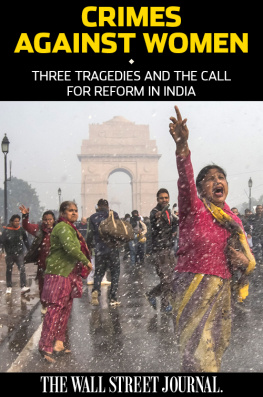

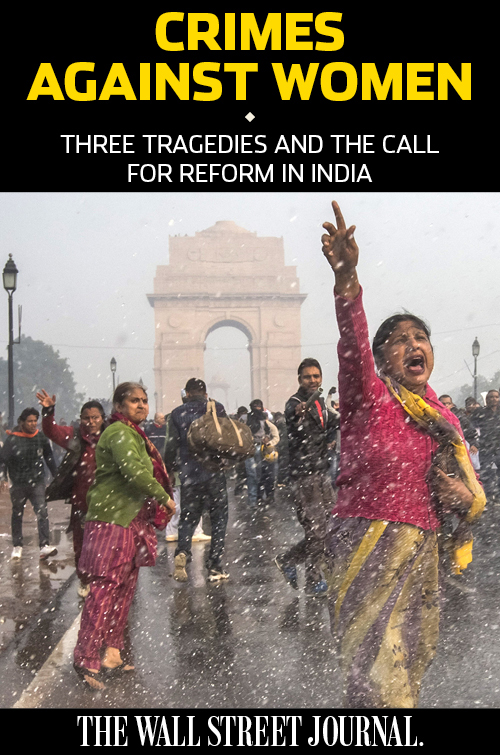

A s 2012 came to a close, news of the gang rape of a young woman on a bus in Indias capital generated headlines around the world. The December 16 assault on her by men wielding a metal rod, and her death two weeks later from her injuries, challenged the image of modern India as a liberal aspiring superpower of confident young professionals and benign spirituality.

Instead, it focused attention on one of the dark sides of the worlds largest democracy: the struggle that many Indian women face in a country where chauvinistic and misogynistic attitudes prevail despite years of rapid economic growth.

The assault, on a woman who was putting herself through college by working shifts in a call center, laid bare a troubling dynamic: Indian women are pursuing opportunities opened up by education and the economic boom, but a deep-rooted patriarchy means society and its institutions often fail them.

The Wall Street Journal s India bureau explored the plight of Indias women in great detail in the past 12 months. The three stories in this ebook show how the social blight evident in the Delhi rape is a phenomenon across the country, in various forms. What the crimes chronicled here have in common is the failure of society in general, and government institutions in particular, to protect women in vulnerable situations. It is not primarily a question of inadequate laws but of incompetence or venality in their enforcement.

The result is a breakdown in the social compact that is fundamental to the idea of a modern democracy: the equal treatment of its citizens and the right of all individuals to protection under the law and by their government when danger threatens.

Instead, as these stories show, the worlds largest democracy is rife with lawlessness, lacks a safety net to protect its most vulnerable citizens, and frequently shows a blatant disregard, punctuated with flashes of abject brutality, for half its population.

It is a fact of Indian life that is rarely delved into amid the trumpeting of Indias economic success story or of its continued struggle to eradicate poverty. But it is a blight that, unchecked, will have just as much influence on Indias future.

The WSJ s reporting on these issues began with the story of a Catholic nun murdered in rural India as she tried to preserve ancient tribal ways in the face of mining expansion. In her work, Sister Valsa John Malamel faced off against villagers who wanted to reap economic benefits from local mining. She also came to the aid of a woman who had allegedly been raped but whose complaint to the police was not being taken seriously. It may have been a combination of these two separate dynamics, and the threats they posed to local men, that set the stage for a nighttime mob attack that took her life, police contend.

A few months later, the WSJ published an in-depth account of a young woman, Munni Khatoon, from rural Bihar, who was duped into moving to Delhi, where she was forced to marry or go into prostitutionand the disaster for her and her family that ensued. The plight of one of her daughters, dubbed Baby Falak, was national news. The WSJ offered a unique reconstruction of the broader human tragedy.

What Ms. Khatoon and her childrens ordeal revealed was an underbelly of exploitation of women in the heart of Indias capitaland the failure of social services to identify and intervene with children at risk. India has laws that are designed to provide a safety net, even at the village level, for children in need of protection, and the social welfare minister in the familys home state of Bihar acknowledged that little Falaks predicament could have been prevented had those laws been effectively enforced.

But combating human trafficking is not a high priority, and, the minister added, The general public is not even bothered about it. Nor was it bothered about a young woman who was seeking to escape an abusive husband, the father of her kidsuntil after tragedy had struck.

Less than a year after Baby Falaks story gripped the nation, a young woman was on her way home from watching Life of Pi with a male friend when they boarded a bus toward her home. What happened next is the stuff of nightmares: five men and a teenagerthe only other people on the busturned on the couple, beat them, sexually assaulted her, and threw them both out, naked, on the side of a highway. The bus, its inside lights turned off and the victims appeals for help unheard or ignored, plied some of the capitals major thoroughfares for almost an hour unchecked.

Later, when demonstrators took the streets to protest what had happened, and the lack of womens safety in India in general, they were met with volleys from water cannons and charges by police wielding bamboo truncheons.

The WSJ led global coverage of the crime. It published intimate portraits of the victim and her friend, who tried to save her but couldnt. It delved into the lives of their alleged assailants and their communities and backgrounds. And it looked more broadly at the culture of harassment that Indian women face, which sometimes flares into violent crime.

In this ebook, we bring together these stories, updated with fresh details of the individuals lives, to show the hopes and the catastrophes, the bravery and the abuse, that are the daily lot of millions of Indias women. We hope that it will prove insightful reading and provide a meticulously detailed, accurately reported, sensitively told reference point for one of the biggest issues facing one of the worlds most fascinating, and important, countries.

The Murder of Sister Valsa

A WSJ Investigation

BY KRISHNA POKHAREL AND PAUL BECKETT

PACHWARA, India Where isSister Valsa? they demanded. Where is Sister Valsa?

In the dark of night on November 15, 2011, the mobsurrounded the tile-roof compound. They carried bows and arrows, spades, axes, ironrods.

I dont have that information, replied a woman who livedin the house, according to a statement she later gave to a local court.

Youre lying, she was told.

In one corner of a tiny windowless room off an innercourtyard, Valsa John Malamel, a Christian nun, hid under a blanket punching numbersinto her cell phone.

Some men have surrounded my house, and I am suspectingsomething foul, she whispered to a journalist friend who lived several hours driveaway.

Escape at any cost, he said he told her. The call waslogged at 10:30 P.M.

She called a friend who lived in the same village. I havebeen surrounded on all sides, she told him, according to his court statement. Thenthe line went dead.

The Lust

T he landscape of the Rajmahal Hills in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand unfolds in a scruffy mix of deep-red soil, small fields of brown grass, clusters of banana, ficus, and palm trees, and ponds of murky brown water. It is the heartland of the Santhal and Paharia, two of Indias indigenous tribes.

There are small signs of modern life here. Tribe members carry cell phones. A satellite dish sits on the occasional roof. But ancient, pastoral ways persist. The men hunt rabbit with bows and arrows.