A CENTURY OF

ROYALTY

ED WEST

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

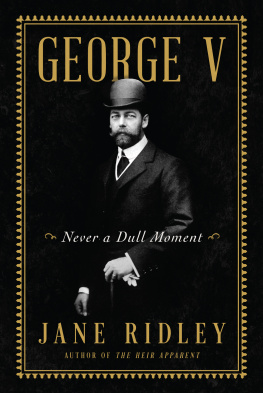

In 1917, towards the end of the First World War, the House of Windsor was born by royal proclamation with George Vs decision to change the family name from the Germanic Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. In many ways this marked the beginning of the age of modern royalty, responding as it did to popular pressure for the royals to disassociate themselves from Britains German enemy.

Living through the overthrow of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburgs, the German Hohenzollerns, and the murder of Russias Romanovs, George V would create in Britain a modern, adaptable royal family for the twentieth century. Unlike his royal cousins, George would survive as king after the epoch-ending First World War to thrive in a new world.

To his granddaughter Lilibet (the future Queen Elizabeth II) he was Grandpa England, but with the skilful use of new technology such as radio broadcasts, he would become a father figure for the nation and the Commonwealth. This idea of a new type of royalty continued under his son George VI, who in key respects transformed the royals into a middle-class family with whom the nation could identify, and helped to hold the country together during the traumas and disruption of the Second World War.

From the first days of modern mass communication to the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the Diamond Jubilee, the royal family has been many things: a national soap opera, with its very own dark moments; a slice of Ruritania in a world of presidents, democracies and dictatorships; a social institution; and an essential part of national identity.

Under Queen Elizabeth II royalty has continued to adapt to the modern world, and despite some bad times, remains the strongest of British institutions. And from the photographs of the funeral of Edward VII, which captured the quaint sight of kings in his cortege who would soon find themselves at war, to the age of Facebook updates for the British Monarchys 620,000 online fans, it is a story told on camera.

Their history is also the most visible and well known of modern Britain, taking in the instability and horror of the First World War, the difficult inter-war period and the life-or-death struggle against Nazism, the social changes of the 1960s and the countrys attempts to find a new place in the twenty-first century. A Century of Royalty captures the major events that have shaped modern Britain, as well as the glamour of royalty, an almost magical force exemplified in extremis by Princess Diana. It illustrates the enormous psychological impact that the royal family (and its individual members) has had on peoples lives, sometimes struggling, but mostly succeeding, in its very public role. Despite the troubles of the 1990s (and of Edward VIIIs abdication) it is the story of the ultimate survivors throughout one hundred years of British history right through to the latest generation and the happy arrival in July 2013 of another royal George.

Edward VIIs Funeral

20 May 1910

In many ways the story of the twentieth century begins with the funeral of Edward VII, the last British king to bear a German surname (and because of his heavily Germanic upbringing, a slight accent). For all the glamour and technological buzz of the Edwardian era the age of the Wright Brothers, Thomas Edison, radio and cinema it was now a distant world of traditional monarchs.

Nine kings and thirty-two princes would follow the coffin of Edward, a popular, jovial figure with a great lust for life (and women and food), whose greatest legacy was the use of royalty as a force for diplomacy. Famously charming and graceful, he arrived in Paris in 1904 to a hostile crowd and left them shouting vive le roi! Alas, Anglo-French rapprochement went in tandem with growing unease at the ambitions of Germany, led by the kings undiplomatic and socially inept nephew, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

As Edwards coffin travelled from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Hall, up Whitehall and the Mall to Marble Arch and Paddington, and by train to Windsor, the king-emperor was mourned by monarchs and princes from across the globe, including representatives from Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary, in the latter case Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

George V and Kaiser Wilhelm II

28 May 1913

Of the four great European monarchies of the year that Franz Ferdinands assassination sparked a world war, only the British House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha would survive, remoulded for the new age.

Just a year before this, King George V visited his cousin Wilhelm in Berlin and was photographed with him, wearing the uniform of the Prussian Food Guards. George V was an honorary officer in the German regiment, much to the disgust of his Danish mother Queen Alexandra, who was still resentful about her countrys 1864 war with Prussia (the Second Schleswig War, famously the most obscure conflict in history, understood by only three people, one of them mad). Kaiser Wilhelm, the son of Queen Victorias eldest child Vicky, had a difficult relationship with Britain, and an inferiority complex. He favoured a more expansionist Germany, but lacked the diplomatic cunning of his grandfathers chancellor Otto Von Bismarck, once unnerving the king of Belgium at a dinner by telling him that he could have a chunk of France in return for military support. It could have been very different; Wilhelms father, Kaiser Friedrich III was a reforming Anglophile who wanted to install a more British-style parliamentary democracy in Berlin, but tragically he died young of cancer. In this photograph, a family similarity can be seen between the king and the kaiser but George had an even closer and even more remarkable physical resemblance.

The First World War

12 August 1916

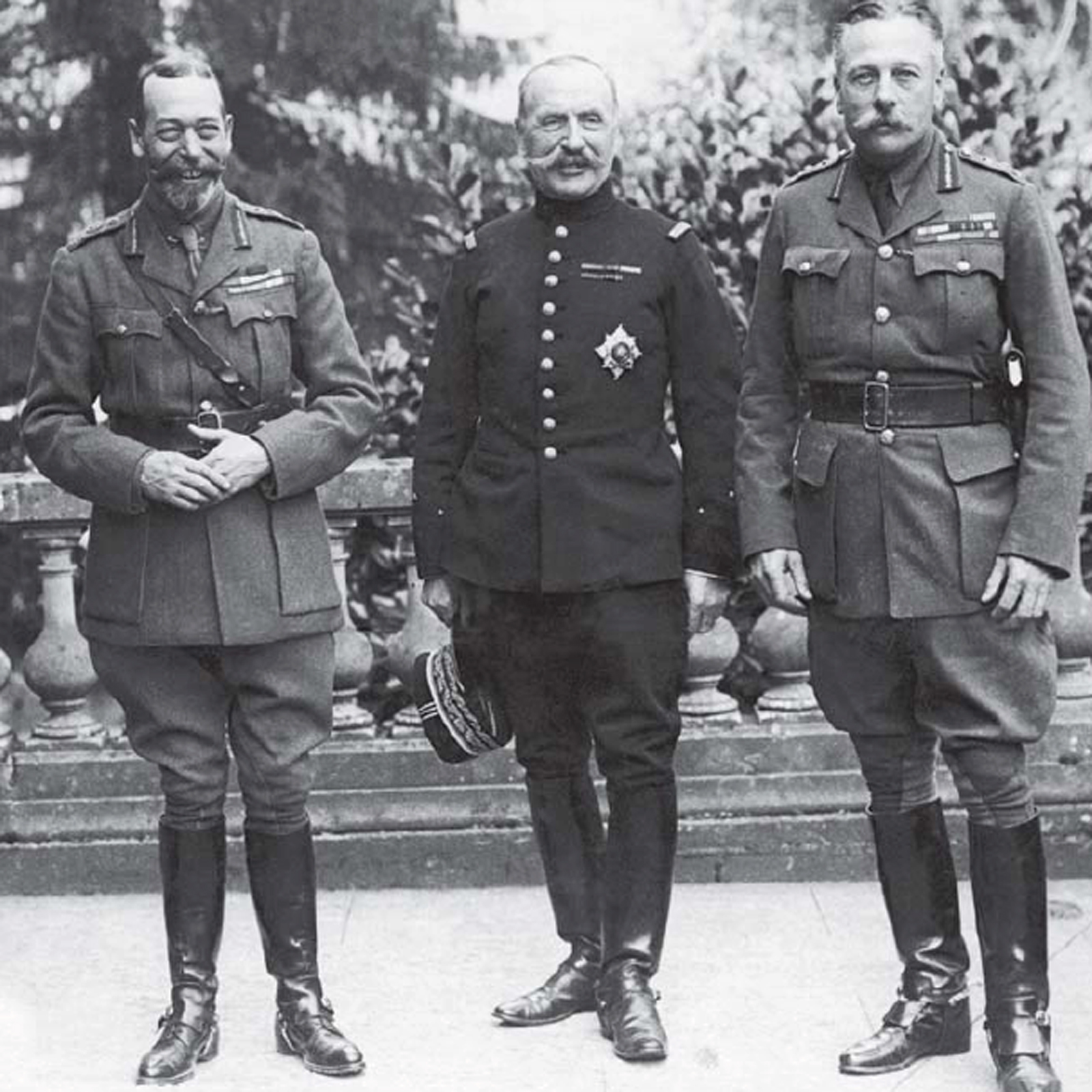

On 1 July 1916 the British launched the offensive that would come to define our view of the First World War the Battle of the Somme. Twenty thousand British soldiers were killed in one day, another 40,000 wounded, and General Haigs reputation would go into freefall as the century went on. George V and Haig are pictured here on either side of the French General Ferdinand Foch on the terrace of Haigs headquarters in Beauquesne, France.

The king had been a rallying point for the British forces, and his wife, Queen Mary of Teck, spent much of the war visiting wounded and dying servicemen, which she found an emotional strain. As the fighting went on, the royal family became increasingly concerned about whether it might survive, and on 27 June 1917 King George changed the family name to Windsor, relinquishing all the German titles held by the family, and stripping fifteen German relatives of British titles.

The spur was the abdication of his cousin, Tsar Nicholas II, and the fear of revolution spreading to England. But it was also unfortunate that from 1916 London was bombed by German aircraft, the most famous of which, the Gotha G.IV, sounded uncomfortably similar to Georges and the royal familys name. The Bolsheviks murdered Tsar Nicholas, his wife and five children, while the kaiser ended up exiled to the Netherlands where he died in 1940.

The Prince of Wales Visiting Curran Munitions Works, Cardiff

February 1918