MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

www.transitlounge.com.au

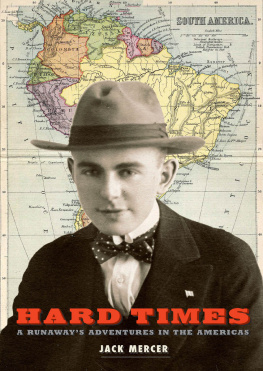

Copyright Brett Pierce 2013

First Published 2013

Transit Lounge Publishing

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

Cover and book design: Peter Lo Back cover image courtesy of NYC Municipal Archives

Printed in China by Everbest

Cataloguing-in-publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia: http://catalogue.nla.gov.au 978-1-921924-54-5 (e-book)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

THE FUGITIVE

The grandfather clock in the dining room began to strike the fateful hour of nine, the hour I had been waiting for all day. Indeed, for many days before, and months throughout the years, I had been living with but a single thought the day when I would be big enough to run away from this hotel, which had been my home for the past four years. Yet as I listened to the metallic, repetitive striking of the clock on the floor above, I felt a sensation of numbness, a strange feeling of unreality. Could it really be the last time that I would sit on my bed, in this narrow little room that had been my sole, unloved refuge for so long?

Mechanically I clutched my wicker picnic basket, which I had packed with such zeal only a short hour ago, when I had collected my worldly possessions together, ready to flee when the time came. Yet here was I still sitting, listening as the tocsin was striking the hour away six, seven, eight Never had it sounded so unrelenting, seeming to compel, to urge me to move while the slender chance of escape still lay open to me. As the last stroke of nine boomed out loud and clear, my breath quickened. My heart began pounding against my ribs. Jumping up, still clutching my basket, I grabbed my overcoat and cautiously opened the door then tiptoed the length of the kitchen towards the flight of stairs, which led outside.

So far the coast was clear. My stepfather was occupied serving behind the bar, exchanging quips and laughter with his boon companions, and I knew that my mother had retired early. The servants had dispersed to their homes or rooms after the long hard day of toil. Downstairs was silent, deserted. The only sound was the creaking of wooden steps under my weight, and I heaved a sigh of relief as I felt the warm night air on my face. I was out of the house!

Now the moon hid behind the clouds in an overcast sky, but I needed no light to guide my feet along the familiar ground of our backyard, with its stones and holes which I knew so well since I had swept it every day of my life. I involuntarily shuddered as I came parallel with the stable, the scene of the last merciless flogging I received at the hands of my stepfather when he was in his cups.

Was it really three weeks ago? My whole body still smarted and ached, while my right hand was so stiff and swollen that I had to put my basket down and lift the latch of the gate with my left hand. So far, so good. I was out behind the hotel in a dark lane, flanked by an open sullage gutter which was another one of my daily chores to clean and disinfect. I smiled to myself. Never again would I have to slosh in that evil-smelling muck. I began to breathe easier as I crept along, hugging the fence, keeping within the protection of its shadow.

Barely had I gone a hundred yards, when a gate across the lane creaked open just as a cloud rolled back, and the pale light of the moon revealed the figure of Constable Dansforth. He peered at me closely, and to my complete surprise greeted me in a most casual tone.

Hello there, young Jack. You gave me quite a start!

I gave him a start? Why, I couldnt even trust my voice to speak lest it betrayed my inward tremor. What could I say if he asked me where I was going? My mind groped for an answer in vain, but my good friend asked no questions as he fell into step beside me. He began talking pleasantly about local sporting gossip, the cricket season and the unusually hot weather for this time of the year, while I wondered uneasily if he had spied my winter coat draped over my basket. The moon above came to my rescue again and retreated behind the clouds, thank heavens!

Finally we turned up the lane leading to the main thoroughfare, and emerged into the gaslit street, where my companion nonchalantly bid me a friendly, Goodnight, young Jack, and strode off across Barkly Street to commence night duty at the police station.

I lost no time scurrying into the protective shadows of the lane opposite, on the other side of Barkly Street, where it meandered the full length of our town towards the main road and open fields beyond. Here I broke into a panicky run. The constable must have delayed me and I had no time to spare, for I had to cover six miles to Dobie railway siding, where I deemed it would be safe for me to board a train. I had reasoned it all out before. It would have been stupid to board the train at our Ararat station. I ran and walked, stumbled and ran on again as fear gripped me afresh. What if I missed my train? Where would I spend the night?

For a fleeting moment I considered returning and creeping back into my room, rather than risk being caught to be flogged again. No, I kept telling myself. I would never get this chance twice. I must go on. How, after so much careful planning and calculating every move of my escape, could anything now go amiss? Had I not plotted every step, worked out every detail of this crucial event when I would dash for freedom, even to timing a complete rehearsal of the Dobie walk?

As I panted and hurried on, a stabbing pain seized my side. I paused for breath, gulping down great draughts of air, trying to fill my lungs and clear my head. To reassure myself, I put my hand in the pocket of my short pants and fingered the notes resting there against my thigh. The feel of that currency of three pounds ten helped to calm me down and lessened my doubts and fears, as I resumed the alternative running and walking drill along the narrow lane, and onto the open road ahead.

Not a soul passed. No evidence of life stirred in the silent country around me. There was just me and my precious money snuggling against my hand the key to my successful getaway, calculated to put miles between myself and Ararat, to start a new life, to work as a free man. I was determined not to become a swagman or a penniless tramp, or caught by the police wandering around unemployed.

From the very beginning, my chief objective had been to accumulate enough money by the time I reached a reasonable height. Ever since I had turned fifteen, four months previously, I had been measuring myself against the kitchen doorjamb, which I had marked in feet and inches; and at five feet four inches I considered I was tall enough to mix among grown-ups. I felt that I had an even chance of passing inconspicuously in a throng. Money remained the stumbling block to all my schemes of escape.

Not that I did not earn money. My mother always found jobs for me. For the past two years I had worked as a casual telegraph messenger at the post office, and covered many miles of the towns environs peddling an ancient bicycle known universally as the bone shaker. Yet never a penny stayed in my hands longer than it took me to cross the road from the post office to the hotel, where my mother took charge, acting officially as my financial agent!

Next page