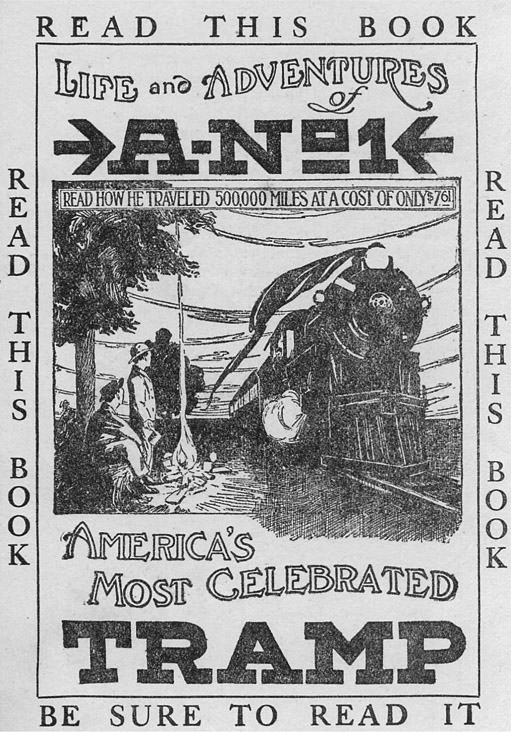

INTRODUCTORY

CHAPTER I.

The Origin of the Tramp.

IN the days before the Civil War, the ragged Brother of the Road, the tramp we nowadays see so frequently, and of whom we hear so many evil reports, and of whose law defying and only too often revoltingly inhuman deeds we read almost daily in the press, was unknown in the United States and in Canada.

Now and anon, with long intervals between their passing, aged and decrepit men were met with, dragging their diseased and poverty racked bodies along the public highways. They were poor fellows whom a cruel destiny had cursed in their old age with dire adversity, and who, too proud to eat the bread of the alms houses, preferred to wander about the land depending for their sustenance upon the morsels mercifully doled out to them by charitable citizens.

The real tramp problem came into active existence only after the close of the Civil War. When the citizen-soldiers who had fought in this sanguinary struggle were discharged from the service, they went back to their homes and there readily exchanged the gaudy trappings of the warriors and the weapons of war for the sober garbs of the civilians and the implements of peace, and commenced anew where they had left off when they had hastened to respond to their countrys call for volunteers.

But among those who had hurried to the front, were countless numbers of mere youths, who had cast aside their school books to serve their country, and who, now that peace had come to the land, had grown to mans estate. When they returned to their homes they discovered that as they had never mastered a trade, they had lived the war existence of a soldier with its bivouacking, its marching and its battling entirely too long; so long in fact, that now it became a most difficult problem to learn, this late in their lives, the secrets of useful trades.

Soon the yoke under which they had to buckle while being cooped up in shops or in factories, became so galling to them, and the routine of the workshops so wearisome that they could not resist the call of the out-of-doors, and they left their benches and their counters, and drifted out upon the public highway to seek employment among the farmers and the ranchers.

Nearly every one of these drifters immediately found a job, while those among them who were less fortunate, quickly discovered that wherever they chanced to stop, the rural population treated them as popular heroes and especially those among the settlers who during the Civil War had remained at home; for to this class, the ex-soldiers tales of the camps and of the battlefields proved a never tiring entertainment, as in those days before the telephone, the rural mail delivery and the many modern blessings, deathly monotony was the bane of the countryside, which these soldier storytellers at least temporarily dispelled, and for which easy task they were amply rewarded by their hosts who furnished them the best they could offer in the line of food and of shelter.

These well-treated travelers spread reports concerning this good thing broadcast about the country and soon many more of the ex-warriors took to the highways. For a year or two the army of story-telling drifters increased, and then when most of them realized that this sort of nomadic and indolent existence offered neither a chance to provide for the paramount trait of human nature, a home, nor even for a future, they voluntarily quit the roving life and accepted steady employment.

Gradually the numbers of the traveling ex-soldiers decreased to such a degree that the rural population offered all sorts of inducements to inveigle this class of story-tellers into sojourning at their farm houses, but in the end all of them disappeared from the highways, leaving the held to the afore-mentioned, aged and decrepit wanderers.

Then came the fateful sixth of September, eighteen hundred and sixty-nine, the day which will be memorable by its accursed epithet Black Friday, and on which day legions of the wealthiest citizens in the land were reduced to penniless paupers, while from end to end of the country, banks closed their doors and as a logical sequence of the ensuing panic, everywhere shops and factories were forced to suspend operations, casting hundreds of thousands of toilers upon the charity of the world.

Those among the former soldier-drifters who had no families dependent upon them, remembering the good times the public highways provided for them in the past, again returned to the road as a simple method to escape from the jobless cities in which ominous bread and soup lines were a common sight.

Following in the footsteps of these ex-warriors, came other idle men who hoped that the country at large not only offered to them better chances to obtain employment, but would also provide them with ample sustenance until they found jobs.

Once more the highways became the stamping grounds of a floating population of able-bodied men. Soon these wanderers became so numerous that the rural populace which had been most severely nipped by the collapsing of the banks, wearied of feeding the famished horde of out-of-works, and commenced to carefully discriminate between those to whom they doled out their bounties, with the result that many of the drifters, unable by fair means to procure the wherewith to appease their hunger, took by stealth and at times by force, that which they required to keep their souls and their bodies together. These petty crimes so embittered the farmers that the latter finally shut their hands and their homes against every appeal made by the wayfarers.

Good Roads in those early days were never dreamed of and when the jobless, famished men became aware that the farm houses located along the public highways failed to yield sufficient food to compensate them for the exertions required to make progress upon those rut-torn lanes, they made use of the less uneven railroad tracks as paths to wander from settlement to settlement, which latter, with their more dense population, offered superior chances to beg food and to find employment than was offered by the hostile people of the countryside.

Campaigning by the use of the railroad right-of-ways quickly became the common practice of the jobless, and in due time some wise head among them discovered that after dark, when all cats are gray, it required far less exertion to climb into an empty box car of a freight train, and since this style of traveling was quicker and far more congenial to the feet than the tiresome counting of railroad ties, this method of night journeying soon became exceedingly popular among the drifters.

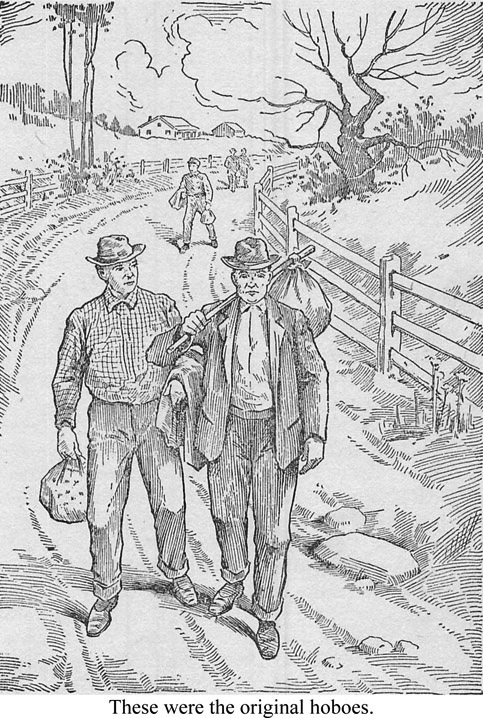

A little later they also discovered that to travel hidden in a box car, even during the broad light of day, was possible since nearly every member of the train crews had been to the war and was actuated by a streak of typical railroad mans good-natured charity, into closing his eyes to these penniless and entirely harmless transgressors of the lawthe original hoboes.

In time, conditions improved so that most of the ex-soldiers and those among the other drifters who were skilled in a trade, voluntarily quit the road by taking employment, while some of them, and nearly all of those who had no regular vocation, continued their box car traveling.

Soon dangerous criminals becoming aware of the fact that the nomadic life of the drifters provided a safe refuge for everyone who had reason to fear the strong arm of the law, promptly took advantage of this knowledge, and thus, not only escaped their deserved punishment, but taught the harmless hoboes everything criminal and perverted they themselves had mastered during their careers of crime. These idling hoboes in turn, taught every new recruit of the hobo army, and especially runaway and restless boys and youths, everything they had learned, and this process has ever since ceaselessly continued, until in our day, the road has earned for itself, at the hands of those who have made criminology their special study, the infamous reputation that in all the wide world it is the one school wherein, within the briefest space of time, anyone may acquire a thorough education in every known variety of crime and degeneracy.