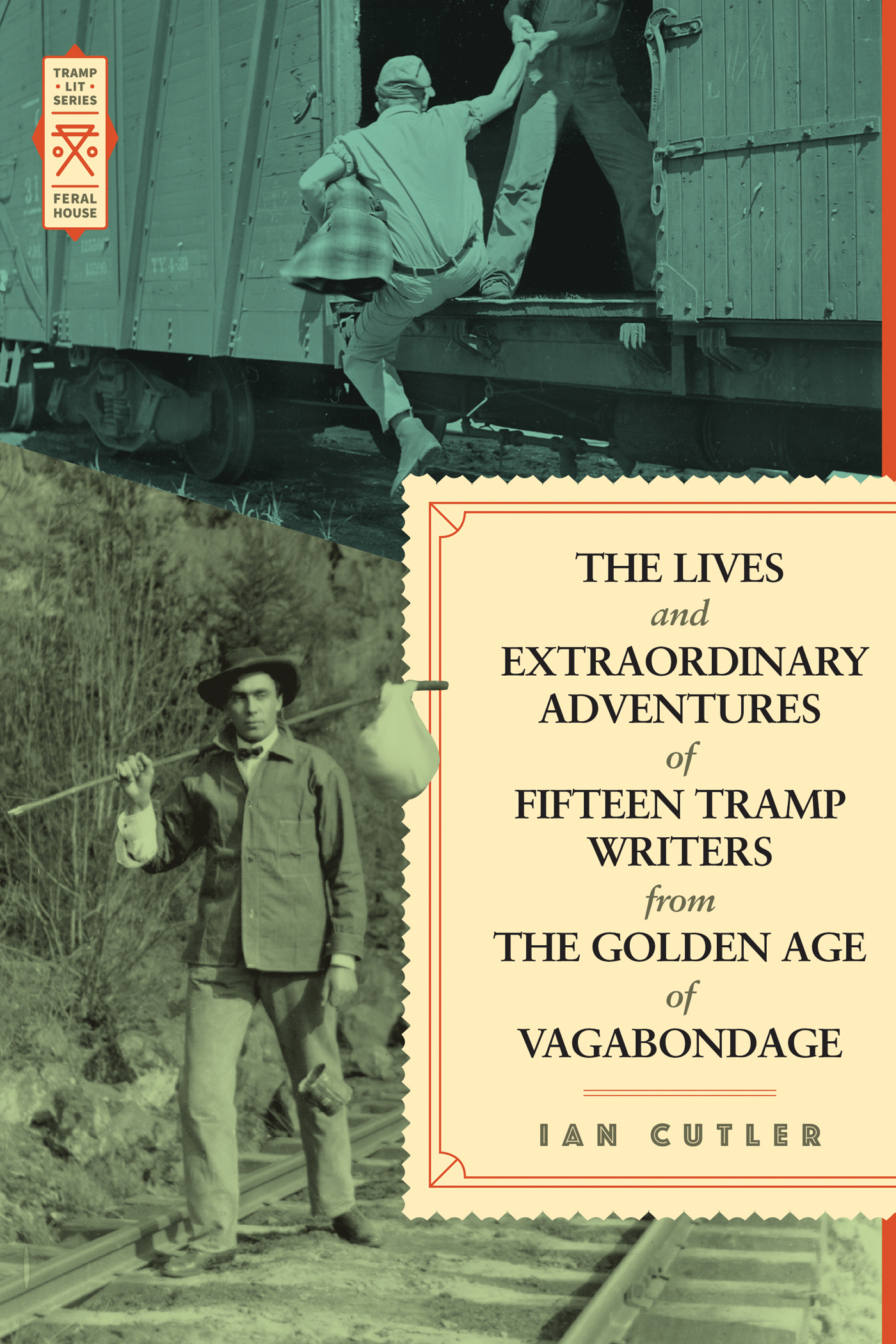

FOR ANGELA

WHO HAS TRAMPED

THROUGH LIFE WITH ME

AND IS ADORED

THE END

by MAX CUTLER

Introduction

A Philosophy of Tramping

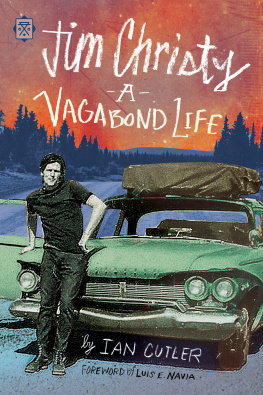

by IAN CUTLER

What made the vagabond so terrifying was his apparent freedom to move and so to escape the net of the previously locally based control. Worse than that, the movements of the vagabond were unpredictable; unlike the pilgrim or, for that matter, a nomad, the vagabond has no set destination. You do not know where he will move next, because he himself does not know or care much.

Zygmunt Bauman

B auman identified an age-old distrust of tramping, a suspicion that can be traced back centuries to fears of wandering strangers, escaped slaves and runaway servants. The periods in history when numbers of homeless and jobless drifters swelled to epidemic proportions mirror the enactment of various vagrancy laws in both Europe and the New World, fueled as they were by a perceived threat of idleness in the population and breakdown of the social order. One of the earliest such laws in Britain dates back to 1349 following the Black Death, others followed prolonged military campaigns, such as the Napoleonic Wars in Europe which gave rise to the 1824 Vagrancy Act in England and Wales, and the tramp scare following the American Civil War which triggered Tramp Acts in many states (and also Black Codes in the South to control freed slaves). Former soldiers, used to a harsh outdoor life, long marches and little thought of anything but their immediate needs, joined other economic migrants, and those who adopted tramping as an alternative lifestyle choice.

Parallel crises can be traced back to ancient times. Following a great gathering of Cynics from all parts of the Greek-speaking world at the Olympic Games in 167 A.D., it was reported that many of the humbler classes in Rome and Alexandria were turning Cynic in such numbers that alarm was expressed at the prospect of work being brought to a standstill. The philosophy of Cynicism itself, which emerged five hundred years before the Cynic scare of the second century A.D., may have been the first recorded organized movement of tramping as a positive lifestyle choice. The philosophy of Cynics, and also that of the modern philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, will be referred to frequently throughout this book because of the direct parallels between their philosophy of tramping and asceticism, and that expressed by the tramp writers whose lives and thoughts are recorded in the pages that follow. But for now, let us stay with the negative portrayal of the tramp, as illustrated by the long list of (mainly) pejorative terms below:

Beggar

Bindlestiff

Boomer

Bum

Derelict

Dingbat

Down-and-out

Drifter

Floater

Flopper

Gonsil

Hobo

Indigent

Itinerant

Jocker

Jungle Buzzard

Landloper

Loafer

Mendicant

Moocher

Padder

Panhandler

Peripatetic

Piker

Plinger

Postman

Punk

Rambler

Ranger

Roamer

Rover

Scatterling

Shellback

Shuttler

Stewbum

Stiff

Stroller

Tatterdemalion

Tramp

Transient

Traveler

Vagabond

Vagrant

Wanderer

Wandering Willy

Wayfarer

Wheeler

Wobbly

and, less frequently but more affectionately, Gentlemen or Knights of the Road, and the British tramps designation for each other as Sons of Rest.

Many attempts have been made to classify these terms, some of which have several meanings. Most frequently quoted is the work of former hobo and radical activist Dr. Ben Reitman, husband of the anarchist Emma Goldman. Reitman wrote at a time when sociologys obsession with classification had reached absurd proportions. In Reitmans study of women tramps, Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Box-Car Bertha, he provides an appendix with over 30 pages classifying women tramps alone. Reitman started riding trains as a hobo from the age of 12, after being abandoned by his Jewish immigrant father. He later qualified as a medical doctor but continued to work with Chicagos burgeoning hobo community, and also with the prostitutes enticed there by the parallel local economy. This came in the form of transient workers returning to the city from other parts of the Midwest where they spent significant sums of money in Chicagos Main Stem from harvesting, logging, mining, and construction work. Reitman was also an early advocate of birth control and abortion, for which he received a six-month jail sentence. The title of the book, from which the passage below is taken, provides adequate testimony to Reitmans achievements: The Damndest Radical: The Life and World of Ben Reitman, Chicagos Celebrated Social Reformer, Hobo King, and Whorehouse Physician. In his role as a sociologist, Reitman classified vagrancy into three main divisions:

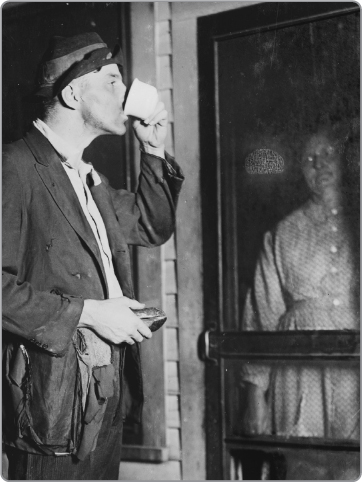

A tramp is a man who doesnt work, who apparently doesnt want to work, who lives without working and who is constantly traveling. A hobo is a non-skilled, non-employed laborer without money, looking for work. A bum is a man who hangs around a low-class saloon and begs or earns a few pennies a day in order to obtain drink. He is usually inebriate.

One-time hobo and Chicago sociologist Nels Anderson was even more obsessed with classifying tramps. A study he commissioned (from other tramps) included five main divisions with 30 subdivisions, further subdivided again. Unlike Reitmans 30-page appendix of women tramps, Anderson cites James Moore (The Daredevil Hobo) who included women as a subdivision of Other Classes along with Cripples, Stew Bums, Spongers, and Old Men, only further subdividing women into three groups: prostitutes, dope fiends and drunks, and mental defectives. Tramps, Reitman and Anderson may have been, but partly due to the coincidence of Chicago becoming a hobo mecca at the turn of the last century, and the birth of the Chicago School of Sociology (responsible for popularizing urban sociology as a specific research area), many of these works on tramping concentrate on sociopolitical and historical investigations rather than getting underneath to the very essence of tramping itself.

This book will deliberately avoid scientific explanations of tramping, rather allowing the phenomenon to be explored directly in the words of those who lived and wrote about it from personal experience. The available literature on tramping, written by actual and self-proclaimed tramps from the middle of the 19th century, is surprisingly rich and abundant. Yet it is difficult to ignore the classification of tramping altogether, as will become obvious from the tramp writings in this book that started to appear within a decade of Charles Dickens penning the following quote from his satirical classification of tramps, The Uncommercial Traveller: A Tramp Caravan (1860):

THE EDUCATED TRAMP the most vicious by far, of all idle tramps is more selfish and insolent than even the savage tramp. He would sponge on the poorest boy for a farthing, and spurn him when he had got it; he would interpose (if he could get anything by it) between the baby and the mothers breast. this pitiless rascal blights the summer road as he maunders on between luxuriant hedges; where to my thinking, even the wild convolvulus and rose and sweetbriar, are the worse for his going by, and need time to recover from the taint of him in the air.

Next page