NOTE TO THE READER

The names of many individuals

in this book

have been changed.

Surah I

AL-FATIHAH, "THE OPENING"

Revealed at Mecca

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Worlds,

The Beneficent, the Merciful.

Owner of the Day of Judgment,

Thee (alone) we worship; Thee (alone) we ask for help.

Show us the straight path.

The path of those whom Thou has favoured;

Not (the path) of those who earn Thine anger nor of those who

go astray.

BAHA'I PRAYER

Glory be to Thee, O Lord my God! .. I beg of Thee to guard this handmaiden who hath fled for

refuge to Thee, and hath sought shelter of Him in Whom Thou Thyself art

manifest, and hath put her whole trust and confidence in Thee...

Contents

20 Prisc^n Life 224

21 Lav LI

22 Riot!

23 York

24 Lehigh

25 Hearing

26 Beijing

27 In Position

28 Battles

29 Desperation

30 Crisis

31 April 24th

32 Freedom Epilogue 5^^ Acknowledgments 5^2 For More Information 5^^

244 263

287 3U 337

372 387 410 431 444 471 489

Prison

I

returned to my cell after lunch. It was time for the Salat adh-Dhuhr.

I removed my shoes and washed my face, arms, feet and hands at the small sink. Then I carefully spread the bedsheet I used as a prayer rug on the cold concrete floor. I wrapped my head and neck in the veil we caD a mayahfi, stepped on the sheet that faced East and began to pray. While I was kneeHng on the sheet, clutching the ninety-nine beads of the tasbih...

"Kasinga!" My neck jerked upward when I heard the sound of my name come crackling out through the prison intercom system.

"Kasinga! Attorney visit!"

So they were here. But I wanted to fmish my prayers.

AUau Akbar, Allan Akbar, Allan Akbar

"Kasinga! Kasinga!"

I stood up, unwrapped my mayahfi, slowly laced my sneakers, and stepped onto the ramp outside my cell. Upper tier in B pod, maximum security, York County Correctional Facility in Pennsylvania this was where I lived.

Down below me I could see the dayroom, a small, barren space with metal tables and stools bolted to the floor. Inmates in blue uniforms passed their time aimlessly, watching TV, playing cards, talking, and staring into space. I slowly made my way along the ramp

to the stairway and down the stairs. The guard in the booth tried to hurry nie along by shouting my name repeatedly over the loudspeaker, but I wouldn't be rushed. I was still reciting my prayers. I had learned that prayer w^as what kept me going, enabling me to see beyond the grim gray walls of this place I was forced to call home.

By the time I reached the door to the hall, it had been opened from the control booth. A guard stood waiting in the doorway. She w^aved me through. "Let's go, let's go!" We turned right and walked a few paces to a doorway. 'Tn here," she said, motioning me into a small meeting room with four metal chairs and a metal table against the far wall. "Wait here," she said, closing the door behind her. I walked to the chair nearest the table, sat down, and waited for my visitors.

It was Saturday afternoon, February 10, 1996, my fourteenth month in prison, six weeks after my nineteenth birthday.

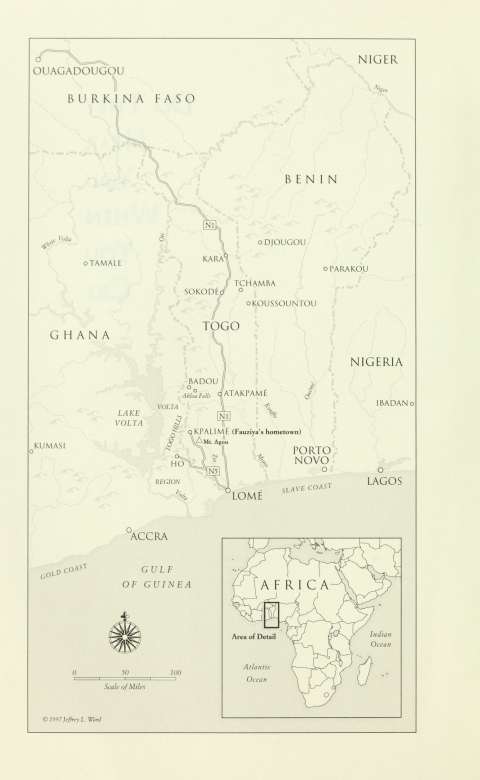

Back home in Togo, when my father was still alive and our family was still together in my father's house, my mother would fast on my birthday. She fasted on all her children's birthdays to thank Allah for keeping us well. Where was my mother now? Had she remembered to fast on my birthday this year? I hadn't seen her in almost three years, since my father's sister, Hajia Mamoud, evicted her from our house, four months and ten days after my father's death.

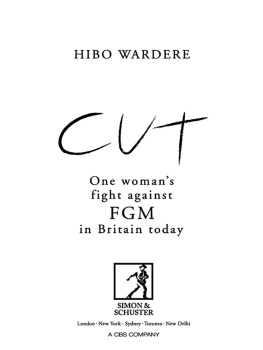

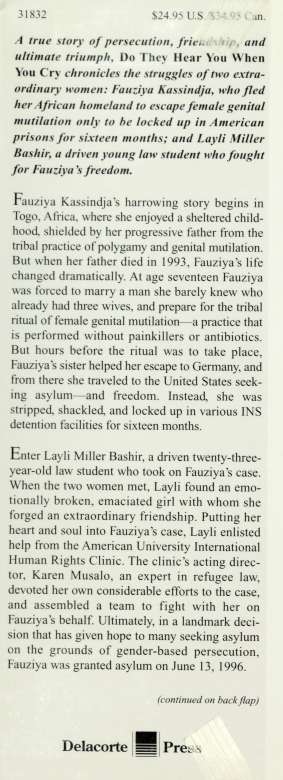

It was because of Hajia Mamoud and my father's brother, Malam Mouhamadou, that I was now thousands of miles away from everything and everyone I loved. When my father died, Malam Mouhamadou became my legal guardian. He and Hajia Mamoud sold me into marriage to a man almost thirty years my senior who already had three wives. This man wanted my woman parts cut off before taking me as his wife. It is a traditional practice in my tribe, which we call kakia. Most people call it female circumcision. But that doesn't really describe what kakia is. Since I've been in this country, I've heard people refer to kakia as female genital mutilation. Mutilation. Yes, that's the right name.

Traditional though my father was, he had opposed this practice, so my older sisters were spared. But I was the youngest of the five girls, and after my father's death there was no one to protect me. When my aunt told me she had arranged my marriage and that I was to be cut, I was terrified because I had known girls who had died from

having it done. My mother's own sister had died from it, and I'd heard my parents speak of this event with horror. But my "husband," hke most men ni our tribe, wanted me to be cut so that I would be "clean" for him. So my aunt had arranged for the women who do It to come to our house.

I've heard that during the procedure, four women spread your legs wide apart and hold you down so that you can't move. And then, the eldest woman takes a knife that is used to cut hair and scrapes your woman parts off. There are no painkillers, no anesthesia. The knife isn't sterilized. Afterward, the women wrap your legs from your hips to your knees and you have to stay in bed for forty days so the wound can close. After the forty days, you are "reborn" for your husband, and delivered to his house to begin your new life as his wife.

This would have happened to me had I stayed in Togo. It happens every day to girls all over the world. But with the help of my oldest sister and money from my mother, I ran away, far from my home, my family, and my country. Eventually I made it to America where I thought I'd be taken in, where I thought I would be safe. But instead of finding safety, I'd found a jail cellor actually a series of cells. I was now in my fourth prison. I had been beaten, teargassed, kept in isolation until I nearly lost my mind, trussed up in chains Hke a dangerous animal, strip-searched repeatedly, and forced to live with criminals, even murderers.

Why? I had committed no crime and was a danger to no one. I was only a nineteen-year-old girl from Togo who desperately needed help. I was a refugee seeking aslyum, not a convicted criminal. I kept asking myself, why is this happening to me? My teachers in Africa said that America was a great country. It was the land of freedom, where people were supposed to fmd justice. But I was delivered to a dark corner of America where there was no justice. There was only cruelty, danger, and indifference.

And now I was ill. Even as I sat waiting for my visitors that day, my chest was burning. Each time I took a breath, it felt like someone was stabbing me with a knife. I was weak because I hadn't eaten much of anything for days. Swallowing food hurt too much. I didn't know what was wrong with me. I had asked to see a doctor several