CONTENTS

About the Book

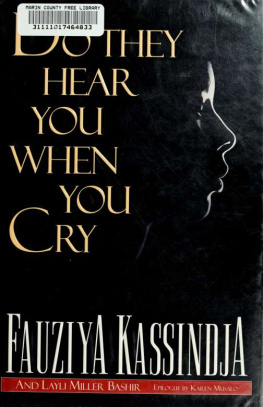

Fauziya Kassindjas harrowing story begins in Togo, Africa, where she enjoyed a sheltered childhood, shielded by her progressive father from tribal practices. But when he died in 1993, her life changed dramatically. At the age of seventeen she was forced to marry a man who already had three wives and to prepare for the ritual of female circumcision. Hours before the brutal ceremony was to take place, Fauziya escaped and fled to the United States to seek asylum. However, her nightmare was far from over. On arrival in America she was stripped, shackled and imprisoned by the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Enter Layli Miller Bashir, a young law student, who took on Fauziyas case and fought for her freedom. In a landmark decision that has given hope to many seeking refuge on the grounds of gender-based persecution, Fauziya was finally granted asylum on 13 June 1996.

In the tradition of the international bestsellers Princess and Not Without My Daughter, this is the dramatic and inspirational story of a woman fighting to free herself from the injustices of her culture. It is a story that you will not easily forget.

About the Authors

Fauziya Kassindja was born in 1977 in Kpalime, Togo, the youngest daughter of a wealthy, prominent family. She now lives in Alexandria, Virginia.

Layli Miller Bashir is a recent graduate from the American University Washington College of Law. She lives in Virginia with her husband.

Do They Hear You When You Cry

Fauziya Kassindja

and

Layli Miller Bashir

1

Prison

I RETURNED TO my cell after lunch. It was time for the Salat adh-Dhuhr.

I removed my shoes and washed my face, arms, feet and hands at the small sink. Then I carefully spread the bedsheet I used as a prayer rug on the cold concrete floor. I wrapped my head and neck in the veil we call a mayahfi, stepped on the sheet that faced East and began to pray. While I was kneeling on the sheet, clutching the ninety-nine beads of the tasbih...

Kasinga! My neck jerked upward when I heard the sound of my name come crackling out through the prison intercom system.

Kasinga! Attorney visit!

So they were here. But I wanted to finish my prayers.

Allau Akbar, Allau Akbar, Allau Akbar

Kasinga! Kasinga!

I stood up, unwrapped my mayahfi, slowly laced my sneakers, and stepped onto the ramp outside my cell. Upper tier in B pod, maximum security, York County Correctional Facility in Pennsylvania this was where I lived.

Down below me I could see the dayroom, a small, barren space with metal tables and stools bolted to the floor. Inmates in blue uniforms passed their time aimlessly, watching TV, playing cards, talking, and staring into space. I slowly made my way along the ramp to the stairway and down the stairs. The guard in the booth tried to hurry me along by shouting my name repeatedly over the loudspeaker, but I wouldnt be rushed. I was still reciting my prayers. I had learned that prayer was what kept me going, enabling me to see beyond the grim gray walls of this place I was forced to call home.

By the time I reached the door to the hall, it had been opened from the control booth. A guard stood waiting in the doorway. She waved me through. Lets go, lets go! We turned right and walked a few paces to a doorway. In here, she said, motioning me into a small meeting room with four metal chairs and a metal table against the far wall. Wait here, she said, closing the door behind her. I walked to the chair nearest the table, sat down, and waited for my visitors.

It was Saturday afternoon, February 10, 1996, my fourteenth month in prison, six weeks after my nineteenth birthday.

Back home in Togo, when my father was still alive and our family was still together in my fathers house, my mother would fast on my birthday. She fasted on all her childrens birthdays to thank Allah for keeping us well. Where was my mother now? Had she remembered to fast on my birthday this year? I hadnt seen her in almost three years, since my fathers sister, Hajia Mamoud, evicted her from our house, four months and ten days after my fathers death.

It was because of Hajia Mamoud and my fathers brother, Malam Mouhamadou, that I was now thousands of miles away from everything and everyone I loved. When my father died, Malam Mouhamadou became my legal guardian. He and Hajia Mamoud sold me into marriage to a man almost thirty years my senior who already had three wives. This man wanted my woman parts cut off before taking me as his wife. It is a traditional practice in my tribe, which we call kakia. Most people call it female circumcision. But that doesnt really describe what kakia is. Since Ive been in this country, Ive heard people refer to kakia as female genital mutilation. Mutilation. Yes, thats the right name.

Traditional though my father was, he had opposed this practice, so my older sisters were spared. But I was the youngest of the five girls, and after my fathers death there was no-one to protect me. When my aunt told me she had arranged my marriage and that I was to be cut, I was terrified because I had known girls who had died from having it done. My mothers own sister had died from it, and Id heard my parents speak of this event with horror. But my husband, like most men in our tribe, wanted me to be cut so that I would be clean for him. So my aunt had arranged for the women who do it to come to our house.

Ive heard that during the procedure, four women spread your legs wide apart and hold you down so that you cant move. And then, the eldest woman takes a knife that is used to cut hair and scrapes your woman parts off. There are no painkillers, no anesthesia. The knife isnt sterilized. Afterward, the women wrap your legs from your hips to your knees and you have to stay in bed for forty days so the wound can close. After the forty days, you are reborn for your husband, and delivered to his house to begin your new life as his wife.

This would have happened to me had I stayed in Togo. It happens every day to girls all over the world. But with the help of my oldest sister and money from my mother, I ran away, far from my home, my family, and my country. Eventually I made it to America where I thought Id be taken in, where I thought I would be safe. But instead of finding safety, Id found a jail cell or actually a series of cells. I was now in my fourth prison. I had been beaten, teargassed, kept in isolation until I nearly lost my mind, trussed up in chains like a dangerous animal, strip-searched repeatedly, and forced to live with criminals, even murderers.

Why? I had committed no crime and was a danger to no-one. I was only a nineteen-year-old girl from Togo who desperately needed help. I was a refugee seeking aslyum, not a convicted criminal. I kept asking myself, why is this happening to me? My teachers in Africa said that America was a great country. It was the land of freedom, where people were supposed to find justice. But I was delivered to a dark corner of America where there was no justice. There was only cruelty, danger, and indifference.

And now I was ill. Even as I sat waiting for my visitors that day, my chest was burning. Each time I took a breath, it felt like someone was stabbing me with a knife. I was weak because I hadnt eaten much of anything for days. Swallowing food hurt too much. I didnt know what was wrong with me. I had asked to see a doctor several times but was never called to see one. I was afraid. Was I dying? Would I die alone in this place?

The meeting I was about to have was with members of my legal team, three people who were fighting for my release from prison: Layli Miller Bashir, Karen Musalo, and David Shaffer. Karen and David were relatively new to my case, Karen having gotten involved only last September, and David at the end of December. I had never met either of them before. But Layli Layli I felt I knew well. She was the young law student who had represented me at my asylum hearing back in August. After we lost that first hearing, she promised she would never leave me. She said she would keep fighting for me until I was free. She was like an angel, someone who had come to rescue me from the living hell I had endured since coming to the United States. Although she is a white American, and I am a black African, we had become sisters.

Next page