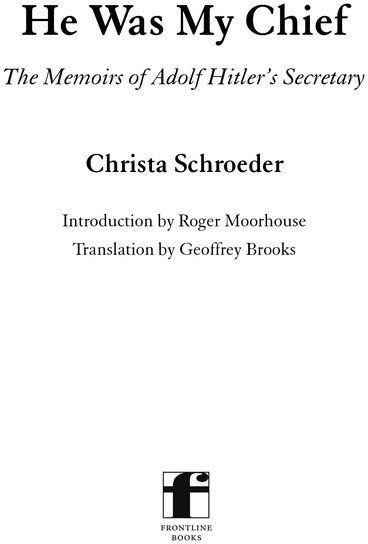

Original German edition:

Er war mein Chef: Aus dem Nachla der Sekretrin von Adolf Hitler

1985 by LangdenMller in der F.A Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, Munich

First published in Great Britain in 2009

Reprinted in this format in 2012 by

Frontline Books

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright LangdenMller in der F.A Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, 1985 English translation copyright Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2009 Introduction Roger Moorhouse, 2009

9781783030644

Er war mein Chef: Aus dem Nachlass der Sekretrin von Adolf Hitler was first published

in German by LangdenMller in der F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH,

Munich, in 1985. He Was My Chief is the first English language edition of the

text and includes a new introduction by Roger Moorhouse. Material relating to

the authors internment and post-war relationship with Albert Zoller has been cut from

this edition but details of her trial have been retained. This period in the authors life

has also been summarised in the introduction by Roger Moorhouse. Additional

material has been abridged due to copyright restrictions.

This is the first English language paperback edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

CHRISTA SCHROEDER WAS AN ordinary woman cast into quite extraordinary times. Born in 1908 in the pretty central German town of Hannoversch Mnden, she trained as a stenotypist before moving to Munich in 1930. Whilst there, she replied to an advertisement in the newspaper for a secretarial position at the headquarters of Hitlers stormtroopers the SA. The association thus forged would be a lasting one. Graduating to a position as Hitlers personal secretary in 1933, Schroeder would be part of the Fhrers entourage for the following twelve years, right up the bitter end in 1945.

This memoir, compiled from contemporary notes and letters as well as postwar reminiscences, is Christa Schroeders own record of those extraordinary times. It gives the reader a fascinating insiders viewpoint on many of the salient events of the Third Reich. She expounds not only on political developments such as the Rhm Purge of 1934 or the attempt on Hitlers life in July 1944, but also on military matters from the Polish campaign through to the final collapse of the Nazi regime, which she experienced from the comparative safety of Berchtesgaden.

Yet it is not primarily for her political insights that Schroeder is of interest. Her experiences certainly ranged widely, but there is a backbone to her book which is not concerned with grand politics a subject about which she claimed to have little knowledge or understanding rather it gives an intimate view of the workings of Hitlers household and of the various characters working therein. In this regard, there is a refreshingly gossipy, chatty flavour to the book, as it illuminates some of the foibles and idiosyncrasies of members of Hitlers entourage, as well as addressing more substantial themes such as Hitlers often difficult and mysterious relationships with women.

Hitler looms large in the book, of course. As secretary to the Fhrer throughout the Third Reich, Schroeder knew Hitler as well as anyone and was extremely well placed to comment on his behaviour and personality. Indeed, Schroeder was herself no shrinking violet, and often spoke rather too bluntly to her employer. In the winter of 1944, for instance, she asked Hitler to his face if he still believed that the war could be won. Indeed, it seems that her candour almost became her undoing when she was ostracised by Hitler for a number of months after making the mistake of publicly contradicting him once too often. Yet, for all that, Schroeders is nonetheless a not unaffectionate portrait. Indeed, her presentation of the leader of the Third Reich as a rounded, three-dimensional, human being with likes and dislikes, hopes and fears is fascinating. She details his bourgeois manners, his vehement abstemiousness, his mood swings, even his sense of humour. Her description of Hitler is not of the wide-eyed fanatic, so familiar to the modern reader; rather he appears as a generous even avuncular benefactor, a kisser of ladies hands; a man who chatted easily with his secretaries and had a passion for Bavarian apple cake.

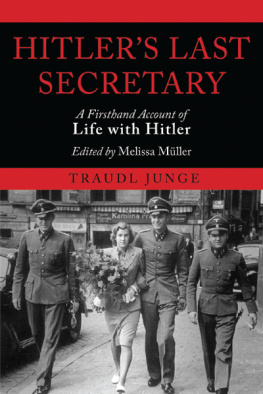

For all its gossipy revelations, however, there is a dark side to Schroeders story. For one thing, the tone of her book is utterly unapologetic; there is nothing, for example, of the sense of perspective or mea culpa that one finds in the memoirs of Hitlers other secretary, Traudl Junge who famously concluded that we should have known about the horrors of the Third Reich. This lack of remorse is, in part, a consequence of Schroeders rather cantankerous character: even the editor of this volume, Anton Joachimsthaler, described her as tough, extremely critical and even wounding in her ways.

Yet there is more to it than that. Schroeder claimed convincingly, I think to have known nothing of the horrors of the Nazi regime and of the crimes being committed in Germanys name. One might legitimately ask how a secretary in the Reich Chancellery could have long remained ignorant of the Holocaust. Yet, for all her closeness to the epicentre of power in Hitlers Germany, Schroeder would have argued that hers was a rather mechanical task largely restricted to the typing up of speeches and mundane daily correspondence, in which such events were rarely mentioned, or else couched in an impenetrable fog of euphemisms and double-speak. The most sensitive of instructions, of course, would always have been transmitted in person, thereby leaving little or no paper trail. Moreover, Schroeder was if anything too close to Hitler and the Nazi elite too close to gain an objective view, too close to question the propaganda, too close perhaps to catch a glimpse of the ugly truth. Confined in the rarefied atmosphere of Hitlers court in the eye of the Nazi storm Schroeder was effectively insulated from the grim realities of the world outside.

As the logical corollary to this ignorance, Schroeder found it difficult to imagine that she personally had done anything reprehensible. Nonetheless, classified by the Americans as a war criminal of the first order, she was interned for three years after 1945. This treatment evidently rankled. As she complains in this book: Whether my guilt was as great as my expiation is something I do not know to this day.

There were further grounds for her bitterness. After the war, she was interrogated at length by Frenchman Albert Zoller, who was serving as a liaison officer with the US Seventh Army. Zoller typed up and embellished his interrogation notes and published them under his own name as Hitler Privat , in 1949, describing the work as the memoir of Hitlers secret secretary, but with Schroeder receiving no credit and, of course, no royalty. She would later complain that Zoller had also taken many of the material mementoes Hitlers sketches etc. that she had been given or had rescued from the ruins of the Third Reich. But, what rankled most perhaps, was that she claimed that he had also appended her name to various comments, opinions and anecdotes that she had never given.

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary: A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/uploads/posts/book/858776/thumbs/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a.jpg)