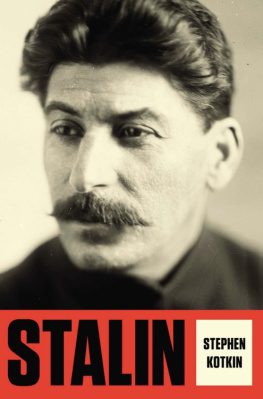

Stephen Kotkin - Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928

Here you can read online Stephen Kotkin - Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Penguin Press HC, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Press HC

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

It has the quality of myth: a poor cobblers son, a seminarian from an oppressed outer province of the Russian empire, reinvents himself as a top leader in a band of revolutionary zealots. When the band seizes control of the country in the aftermath of total world war, the former seminarian ruthlessly dominates the new regime until he stands as absolute ruler of a vast and terrible state apparatus, with dominion over Eurasia. While still building his power base within the Bolshevik dictatorship, he embarks upon the greatest gamble of his political life and the largest program of social reengineering ever attempted: the collectivization of all agriculture and industry across one sixth of the earth. Millions will die, and many more millions will suffer, but the man will push through to the end against all resistance and doubts.

Where did such power come from? In Stalin, Stephen Kotkin offers a biography that, at long last, is equal to this shrewd, sociopathic, charismatic dictator in all his dimensions. The character of Stalin emerges as both astute and blinkered, cynical and true believing, people oriented and vicious, canny enough to see through people but prone to nonsensical beliefs. We see a man inclined to despotism who could be utterly charming, a pragmatic ideologue, a leader who obsessed over slights yet was a precocious geostrategic thinkerunique among Bolsheviksand yet who made egregious strategic blunders. Through it all, we see Stalins unflinching persistence, his sheer force of willperhaps the ultimate key to understanding his indelible mark on history.

Stalin gives an intimate view of the Bolshevik regimes inner geography of power, bringing to the fore fresh materials from Soviet military intelligence and the secret police. Kotkin rejects the inherited wisdom about Stalins psychological makeup, showing us instead how Stalins near paranoia was fundamentally political, and closely tracks the Bolshevik revolutions structural paranoia, the predicament of a Communist regime in an overwhelmingly capitalist world, surrounded and penetrated by enemies. At the same time, Kotkin demonstrates the impossibility of understanding Stalins momentous decisions outside of the context of the tragic history of imperial Russia.

The product of a decade of intrepid research, Stalin is a landmark achievement, a work that recasts the way we think about the Soviet Union, revolution, dictatorship, the twentieth century, and indeed the art of history itself.

Stephen Kotkin: author's other books

Who wrote Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.