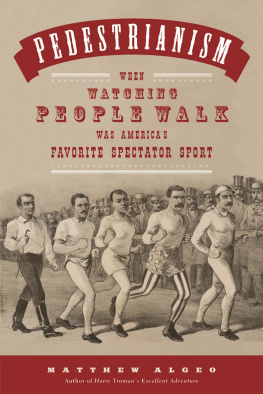

STRANGE AS IT SOUNDS, during the 1870s and 1880s, Americas most popular spectator sport wasnt baseball, boxing, or horseracingit was competitive walking. Inside sold-out arenas, competitors walked around dirt tracks almost nonstop for six straight days (never on Sunday), risking their health and sanity to see who could walk the farthest500 miles, then 520 miles, and 565 miles! These walking matches were as talked about as the weather, the details reported from coast to coast.

This long-forgotten sport, known as pedestrianism, spawned Americas first celebrity athletes and opened doors for immigrants, African Americans, and women. The top pedestrians earned a fortune in prize money and endorsement deals. But along with the excitement came the inevitable scandals, charges of dopingcoca leaves!and insider gambling. It even spawned a riot in 1879 when too many fans showed up at New Yorks Gilmores Garden, later renamed Madison Square Garden, and were denied entry to a widely publicized showdown.

Copyright 2014 by Matthew

Algeo All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-397-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Algeo, Matthew.

Pedestrianism / Matthew Algeo.

pages cm

Summary: Strange as it sounds, during the 1870s and 1880s, Americas most popular spectator sport wasnt baseball, football, or horse racingit was competitive walking. Inside sold-out arenas, competitors walked around dirt tracks almost nonstop for six straight days (never on Sunday), risking their health and sanity to see who could walk the farthest500 miles, then 520 miles, then 565 miles! These walking matches were as talked about as the weather, the details reported in newspapers and telegraphed to fans from coast to coast. This long-forgotten sport, known as pedestrianism, spawned Americas first celebrity athletes, the forerunnersforewalkers, actuallyof LeBron James and Tiger Woods. The top pedestrians earned a fortune in prize money and endorsement deals. The sport also opened doors for immigrants, African Americans, and women. But along with the excitement came the inevitable scandals, charges of dopingcoca leaves!and insider gambling. PEDESTRIANISM chronicles competitive walkings peculiar appeal and popularity, its rapid demise, and its enduring influenceProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-397-3 (hardback)

1. WalkingUnited StatesHistory19th century. 2. SpectatorsUnited StatesHistory19th century. I. Title.

GV199.4.A43 2014

796.510973dc23

2013045115

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

T O Z AYA T HERESA A LGEO

Born January 31, 2013

We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to returnprepared to send back our embalmed hearts only as relics to our desolate kingdoms.

H ENRY D AVID T HOREAU, Walking

CONTENTS

I NDEX

PREFACE

D AN O LEARY S TAGGERED AROUND the dusty track on the floor of Madison Square Garden like a drunken man. Sweat streamed down his face, saturating the bandanna he wore tied around his neck. The thousands in attendance watched in stunned silence as OLeary struggled to stay on his feet, his emaciated body bent like a wheat stalk in a thunderstorm. His countenance was appalling: mouth agape, cheeks hollow, eyes barely open. One spectator said he looked like a corpse. But nobody looked away. The audience was transfixed.

It was noon on Wednesday, March 12, 1879, the third day of the Astley Belt race, a six-day walking match to determine the worlds champion pedestrian. This was the biggest sporting event of the year, a Gilded Age version of Wimbledon or the Masters golf tournament, and Dan OLeary, an Irish immigrant from Chicago, was Americas best hope for winning the race. Hed been circling the Ms-mile oval inside the Garden for two and a half days, practically nonstop. Hed completed 1,624 laps203 milesbut was still more than thirty miles behind the race leader, an Englishman named Charles Rowell. OLeary had walked nearly three thousand miles in various competitions over the previous twelve months, and now his body was broken.

Later that afternoon, OLeary retreated to his tent and collapsed on his bed. A doctor summoned to examine OLeary declared him simply used up.

At 5:36 PM , OLeary limped to the judges stand.

Gentlemen, he announced, I have finished.

The crowd gasped. Western Union carried the news instantly by telegraph across the country. Within an hour, extra editions of newspapers began appearing on street corners from New York to San Francisco, announcing the shocking news in bold front-page headlines: OL EARY Q UITS .

Dan OLearys withdrawal from the Astley Belt race was national news because, at the time, competitive walking was the most popular spectator sport in the United States. In the 1870s and 1880s, fans regularly packed massive arenas like the first Madison Square Garden and Chicagos Interstate Exposition Building, paying twenty-five or fifty cents apiece to watch people walk in circles for days at a time. As one newspaper pointed out, a great walking match was as talked about as the weather. (Running was sometimes allowed; however, as we shall see, it was not an especially effective strategy.)

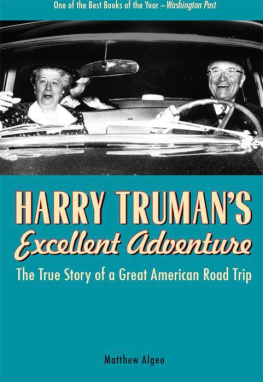

This sport, known as pedestrianism, spawned Americas first celebrity athletes, the forerunnersforewalkers, actuallyof LeBron James and Tiger Woods. Dan OLeary was as famous as President Chester Arthur (himself a huge fan of the sport). The top pedestrians earned a fortune in prize money and endorsement deals (OLeary was the spokesman for a brand of salt), and their images appeared on some of the first cigarette trading cards, which children collected as avidly as later generations would collect baseball cards. The sport opened doors for immigrants, African Americans, and women, affording those underprivileged groups unprecedented opportunities for status and wealth. Less laudably, pedestrianism also gave professional sports its first doping scandal.

Its no coincidence that pedestrianisms rise coincided with the Industrial Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth century, rapid increases in mechanization and urbanization resulted in something previously unimaginable to all but the very rich: leisure time. For the first time, millions of ordinary people had free time on their hands, and many chose to spend it watching other people walk. What does that say about them and their times? And what does it say about us and ours that we regard them as quaint, even simple, for having done so?

In the following pages, we will examine competitive walkings peculiar appeal, its rise and fall, and its enduring influence. In many ways, pedestrianism marked the beginning of modern spectator sports in the United States. Never before had so many people attended (and, not coincidentally, wagered on) athletic events. Never before had the media devoted so much attention to them. NASCAR, the National Football League, even sports radioall are legacies of pedestrianism.

Pedestrianism also animated the major issues of its era: American-British relations, class warfare, racial injustice, womens rights, religious zealotry. Some of these will seem all too familiar to modern readers. An international superpower gets bogged down in a war in Afghanistan, America is riven by a bitter debate over immigration, and a world-famous athlete finds himself accused of using performance-enhancing drugs. The story of pedestrianism is really the story of its time, a period of rapid technological and social changemuch like our own.

Next page