Sommaire

Pagination de ldition papier

Guide

Copyright 2020 by Matthew Algeo

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-64160-062-0

Poem The Dreamer courtesy of Lawrence Baldridge.

Portions of chapter 9 have previously appeared, in substantially different form, as an article in the online magazine Were History.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Typesetting: Nord Compo

Map design: Chris Erichsen

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

The Dreamer

by Lawrence Baldridge

He came a light to our mountains.

A young man burdened with personal tragedy,

And pained with a nations lost direction

In a war that consumed youth, idealism, and a nations dignity.

He came a light to our mountains,

In a nation divided by class and prejudice;

And had himself championed civil rights for all

Whatever ones class, or creed, or color.

He came a light to our mountains

On unpaved roads, past humble dwellings, down endless hollars.

And this Dreamer, this Joseph, found himself inside another dream,

The dream of Alice Lloyd of Boston, our college founder.

He came a light to our mountains

And spoke eloquently and passionately to the students of Alice Lloyd:

And they dreamed with him,

Dreamed of peace among nations, of good will to all mankind.

He came a light to our mountains

And seemed so much at home.

He spoke here, walked here, slept here, ate here.

Robert Kennedy came to Caney Creek!

And the light still shines!

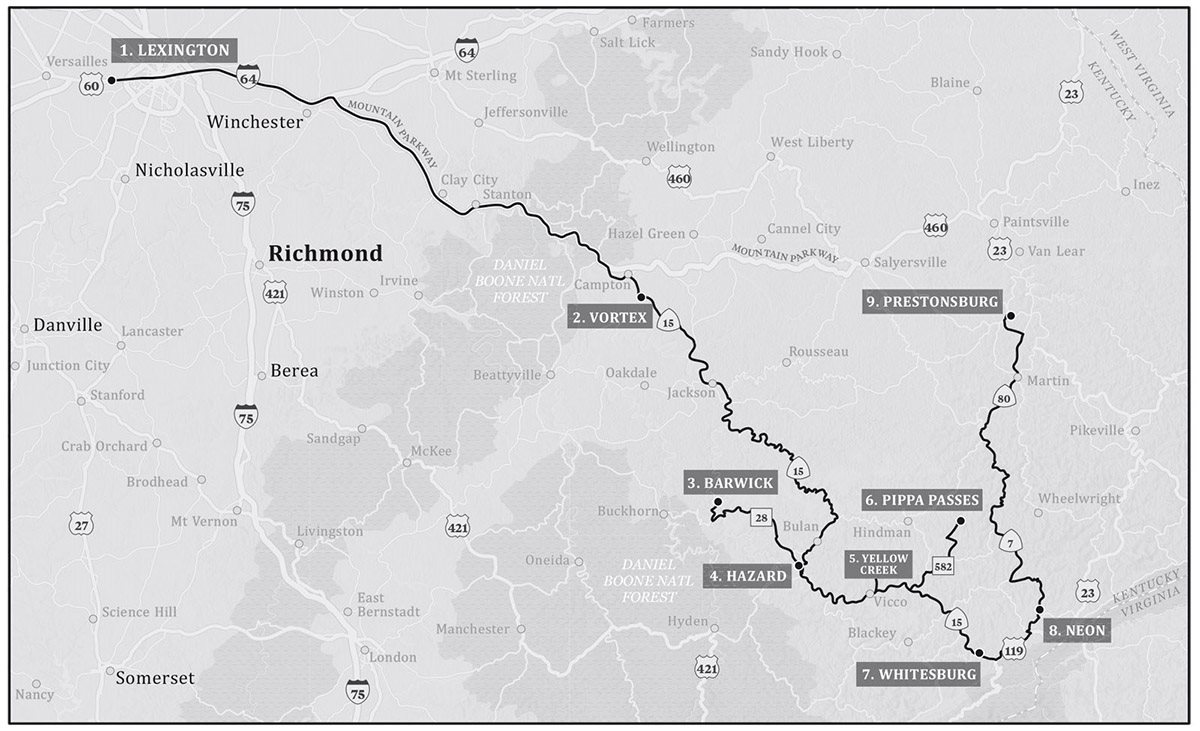

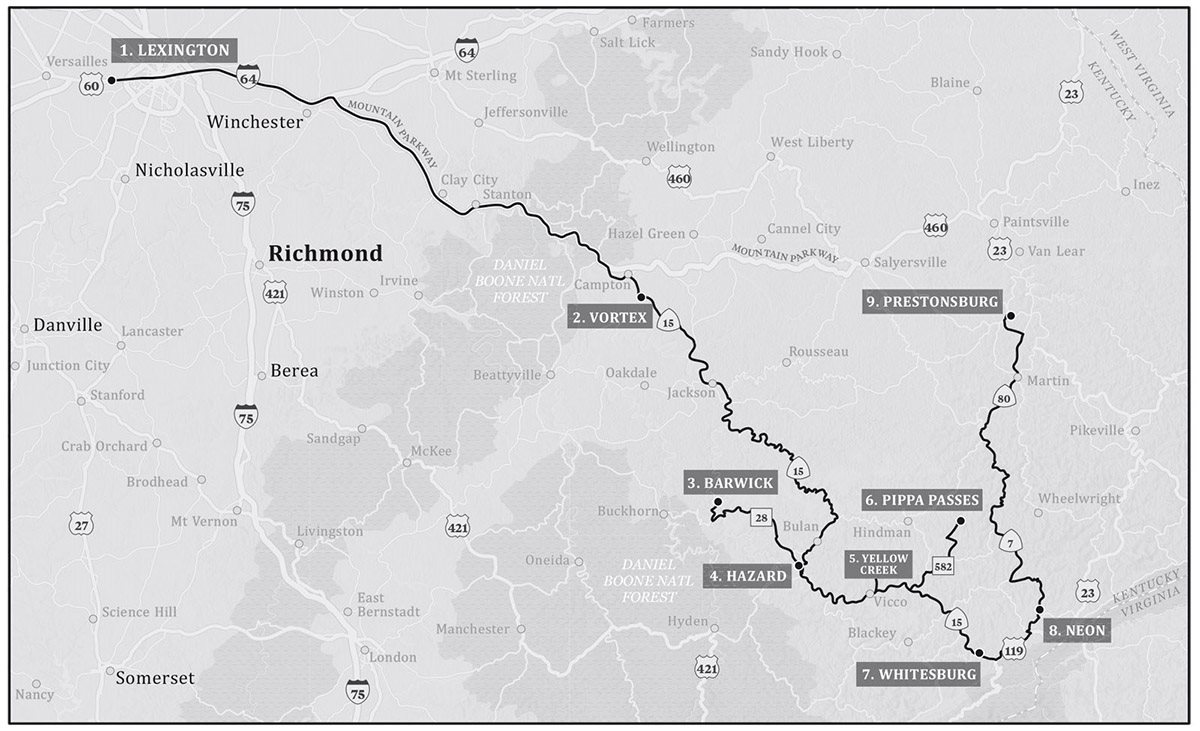

Robert F. Kennedys Itinerary

All times are approximate.

Tuesday, February 13, 1968

11:00 AM | Arrives at Blue Grass Airport in Lexington on Eastern Airlines Flight 659, is greeted by former Kentucky governor Albert Benjamin Happy Chandler. |

11:30 AM | Departs the airport in a state-owned vehicle provided by Kentuckys recently elected Republican governor, Louie Nunn. A state trooper is behind the wheel. Riding along are Congressman Carl D. Perkins and Steve Cawood, a University of Kentucky law student. A large caravan of reporters follows. |

1:00 PM | Arrives at the one-room schoolhouse in Vortex, Wolfe County, where he convenes a one-man hearing of the Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty. Among those testifying are Swango Fugate, a disabled miner from Breathitt County, and Mary Rice Farris, an African American activist from Madison County. |

2:30 PM | Visits poor families in Breathitt and Wolfe Counties; inspects the one-room schoolhouse in Barwick, Breathitt County, where he meets the teacher, Bonnie Jean Carroll, and her students. |

3:30 PM | Tours Liberty Street, the predominantly African American neighborhood in Hazard, Perry County. |

5:00 PM | Inspects a strip mine at Yellow Creek, near Vicco, Perry County. |

7:00 PM | Arrives at Alice Lloyd College in Pippa Passes, Knott County. Holds a ninety-minute question-and-answer session with approximately two hundred students in the schools auditorium and overnights in the home of one of the colleges vice presidents. |

Wednesday, February 14, 1968

8:00 AM | Delivers brief remarks on the steps of the Letcher County Courthouse in Whitesburg. |

10:00 AM | Convenes a hearing of the Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty in the gymnasium of Fleming-Neon High School in Neon, Letcher County. Among those testifying are Tommy Duff, a senior at Evarts High School in neighboring Harlan County, and David Zegeer, the manager of Bethlehem Steels mining subsidiary in eastern Kentucky. |

1:30 PM | Departs Neon. Visits families in Jackhorn, McRoberts, and Haymond, Kentucky. |

4:30 PM | Delivers brief remarks on the steps of the Floyd County Courthouse in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. |

4:00 PM | Flies from a small airport near Prestonsburg to Louisville on Governor Nunns plane. |

6:00 PM | Attends a reception in his honor at the home of Mary and Barry Bingham Sr., publishers of the Louisville Courier-Journal. |

Introduction

THE APPALACHIAN MOUNTAINS WERE FORMED about three billion years ago, when all the continents came together to form a single giant supercontinent that geologists call Pangaea.

Somewhere along the Carolina coast, Africa crashed into North Americaalbeit at a speed so slow as to confound human comprehensionand crumpled the eastern half of what is now the United States. Waves of mountains rose up. Over the ensuing two billion years, the weight of the mountains pressed down on deep layers of dead and decomposing organic matter (mostly prehistoric plants), squeezing out the oxygen and turning the mush into peat, which, after another few hundred million years, turned into a carbon-based black rock that burns slowly and emits tremendous heat: coal.

The Appalachians may have once stood as tall as the Himalayas stand today. Time has worn them down, but they are still formidable. And they are still pressing down, and squeezing, in ways both literal and figurative.

Just over fifty years ago, in February 1968, Robert Kennedy, a US senator born into great wealth and privilege, went to the Appalachian Mountains in eastern Kentucky to meet with people born at the opposite end of the social and economic spectrum: disabled coal miners, single and widowed mothers, children whose parents could not afford to feed them adequately.

The trip occurred at a pivotal moment in American historythe Tet Offensive had launched just weeks beforeand at a pivotal moment in Robert Kennedys life: he was mulling a run for the presidency. For two days, Kennedy traveled hundreds of miles up and down the hills and hollows of eastern Kentucky, on what the press dubbed a poverty tour. He visited one-room schoolhouses and dilapidated homes. He held a public hearing in a ramshackle high school gymnasium, sitting behind a wooden table set up in the foul lane. He toured a strip mine and spoke at a small mountain college.

As acting chairman of a Senate subcommittee on poverty, Robert Kennedy went to Kentucky to gauge the progress of the War on Poverty launched four years earlier by his brothers successor, Lyndon Johnson.

Robert Kennedy wasnt merely on a fact-finding mission, however; a cold political calculus was at work too. Kennedy was considering challenging President Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination, but he would need support from white voters to win it. Kennedys main constituencies were dispossessed minorities: African Americans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans. He needed to forge a coalition between them and working-class whites. Lets face it, he told a reporter, I appeal best to people who have problems.

His trip to eastern Kentucky was a dry run for his presidential campaign, an opportunity to test his antiwar and antipoverty message with hardscrabble whites. He was greeted by what one biographer has described as a mixture of adulation and loathing. Young people mobbed him like he was a Beatle, begging him for autographs and tousling his own famous mop top. Their parents, however, were more circumspect. Frustrated by the governments continued inability to improve their livesand by years of unkept promisesthey warned Kennedy of a growing anger toward Washington.