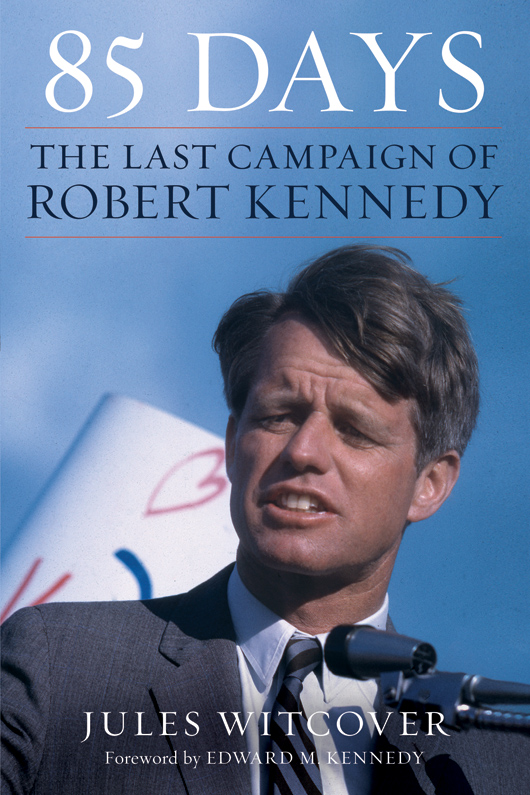

by Senator Edward M. Kennedy

THE YEAR 1968 was not only a year of tragedy for the Kennedy family, it was also a watershed year in contemporary American history. I often think of the might have beens of 1968. If Robert Kennedy had lived, he might well have been elected President of the United States, and our entire subsequent history would have been different and better. We might have been spared much of the divisiveness and confrontation that have plagued the nation since then.

I also remember 1968 as a time of great energy and hope, when a majority of the American people first realized that the Vietnam War was wrong, and that it ought to end. Initially, Robert Kennedy had been reluctant to run for president, fearing that his presence in the campaign would divert attention from the issue of the war. He believed that on the war, as on other vital issues of foreign and domestic policy, individuals would make the difference; as he told the students at the University of Capetown in South Africa on his visit there in 1966: Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

It took the better part of a decade after that for America to live up to its ideals and extricate itself from the Vietnam War, but 1968 was the turning point, and Robert Kennedys campaign was part of the turning. This volume, by one of Americas premier journalists, is a vivid chronicle that makes his last campaign come alive again.

In the two decades since Robert Kennedy was taken from us, much has been written about himby scholars and reporters, classmates in school and college, teammates on the playing fields, and friends from his years of public service. They have told of his achievements; of his character, strength, and faith; of his compassion, humor, and love; of his commitment to others and his vision of America. I knew him in each of these ways, but most of all, of course, I knew him as a brother.

After Joe was killed in World War II, Jack wrote that if the Kennedy family ever amounted to much, it would be because of the leadership Joe had provided. The younger members of our familyand I was the youngest of ninefelt that Bobby set the same kind of example for us.

He always kept his eye on me. When I was ten years old at Fessenden School and he was sixteen at Milton Academy, he would call to find out how my studies were going, and how I was behaving. Occasionally, on fall weekends, we would drive to Cape Cod with our friend Lem Billings and spend the night in the garage of the boarded-up summer house, cooking our own food and sleeping on cots. It is one of my fondest memories in growing up.

On the day before the Harvard-Yale football game at New Haven in November 1953, the Harvard houses were scheduled to play the Yale colleges, and my house, Winthrop, was to play Davenport. Bobby was then a young lawyer on the staff of the Hoover Commission, and he happened to be in New York City working on a report. When I called to ask if he could come and watch the game, he said, I would rather play. He drove to New Haven and changed into a borrowed uniform in the back of his car. He arrived unnoticed on the field just before the kickoff, and after making several tackles and pass receptions for Winthrop House, we were well ahead of Davenport, and he decided he was not needed any longer as my substitute. He changed again in his car and drove back to New York. No one, including the master of Winthrop House, realized that the mystery substitute was Bobby.

Once, when we were serving together in the Senate, he rushed from a meeting with Japanese students to the Senate floor to cast a vote. I had been following the debate, and he looked to me for guidance. He shook his head from side to side, and I nodded my head up and down to indicate that he should vote Yes. When our names were called, I voted Yes, but Bobby voted No. There was laughter in the public gallery as visitors wondered why the Kennedy brothers had disagreed. After the vote was over, he sent me a note which said, When I shake my head from side to side and you nod your head up and down, does this mean I am to vote No and you agree? Obviously not. In other words, when I wanted to vote No, I should have nodded my head up and down. You would have shaken your head from side to side; then I would have known just how to vote.

Nothing in life mattered more to him than how his children would develop and what kind of lives they would lead. His relationships in the family were his greatest source of strength. From our father, he gained the strong will and toughmindedness that led some to see him as ruthless; from our mother, he gained a tender heart and gentle spirit; from our older brothers, he gained a competitive spirit and desire for excellence; and from our sisters, he learned the charm and warmth and shyness that were so appealing, not only to his closest friends but to thousands of others who came to know him in public life or saw him on the campaign trail.

He lived his faith and his religion, and he came to view public service as his calling to help the disadvantaged, the poor, and the victims of discrimination. He was totally involved and committed to their cause. He lived for his children and for the future generations of the earth. He urged others to join him in seeking a newer world, and people responded as perhaps to no other public figure of our time.

His public legacy is written in the achievements of those whom he inspired and who have carried on his work. And there is also the private legacy, the memories of those who knew him best, and miss him most.

I miss the Sunday afternoons at Hickory Hill, when we played touch football with his children, or tennis with General Maxwell Taylor and David Hackett. I miss the ski trips in the West, particularly the early morning milk run, as we rode the chairlift together to take advantage of the fresh powder from an overnight snowfall; once, after a long day on the mountain, we came back to the sauna and rolled in the snowand he locked me outside at twenty degrees below zero. I miss the sailing trips off the Maine coast; more than once, we were lost in fog or storms, but he always managed to bring us safely into port.

Most of all, I miss our walks across the Capitol grounds from the Senate floor to the Senate office building in every kind of weather. He would urge me to speak at morning assembly at a local high school in Washington to encourage the students to stay in school and continue their education. He would ask me to round up more support for a fund-raiser in Boston for Cesar Chavezs farm workers. He would describe his trip to the Mississippi Delta and the unacceptable hunger, malnutrition, and poverty he saw there. He would talk about American Indians and the injustices they were suffering. These sudden moments of passing conversation, as much as any speech he made, revealed his passionate concern for the forgotten American, and his consuming desire to make things better. As he liked to say, in a phrase of George Bernard Shaws that became one of the themes of his last campaign, Some men see things as they are, and say why; I dream things that never were, and say why not?