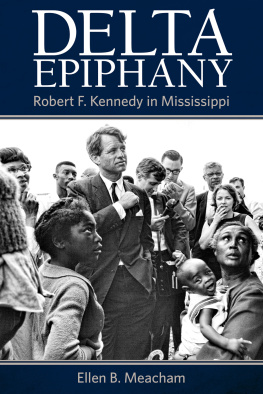

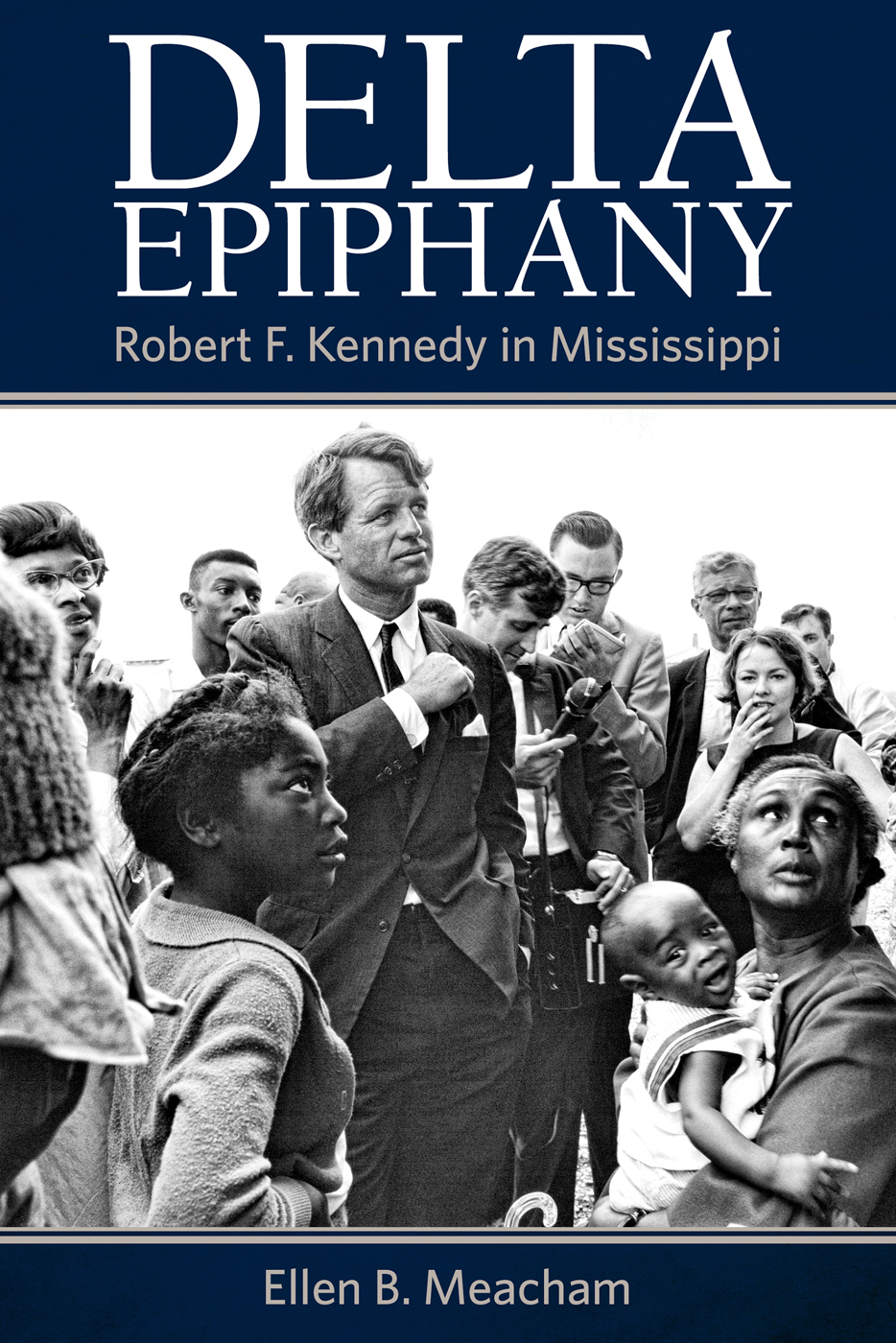

DELTA EPIPHANY

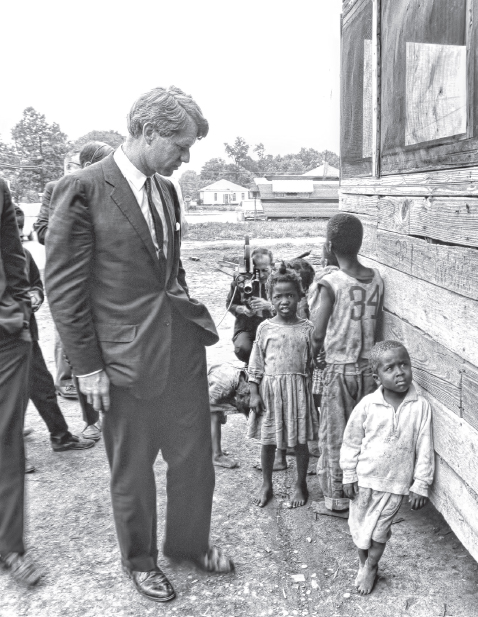

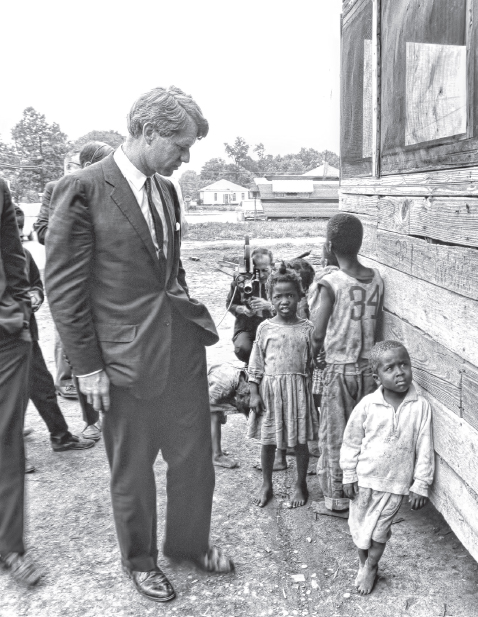

Robert Kennedy in Cleveland, Mississippi. April 11, 1967. Credit: Dan Guravich.

DELTA

EPIPHANY

Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi

Ellen B. Meacham

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2018 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Meacham, Ellen B., author.

Title: Delta epiphany : Robert F. Kennedy in Mississippi / Ellen B. Meacham.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049036 (print) | LCCN 2017051465 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496817464 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496817471 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496817488 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496817495 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496817457 | ISBN 9781496817457 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Kennedy, Robert F., 19251968TravelMississippi. | PovertyMississippiHistory20th century. | African AmericansMississippiEconomic conditions20th century. | United StatesPolitics and government19631969.

Classification: LCC E840.8.K4 (ebook) | LCC E840.8.K4 M39 2018 (print) | DDC 362.509762/0904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049036

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

For Will

To understand the world, you have to understand a place like Mississippi.

Attributed to William Faulkner

Each time a man stands up for an ideal,

or acts to improve the lot of others,

or strikes out against injustice,

he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope,

and crossing each other

from a million different centers of energy and daring,

those ripples build a current which can sweep down

the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

Robert F. Kennedy, Day of Affirmation Address, South Africa, June 6, 1966

CONTENTS

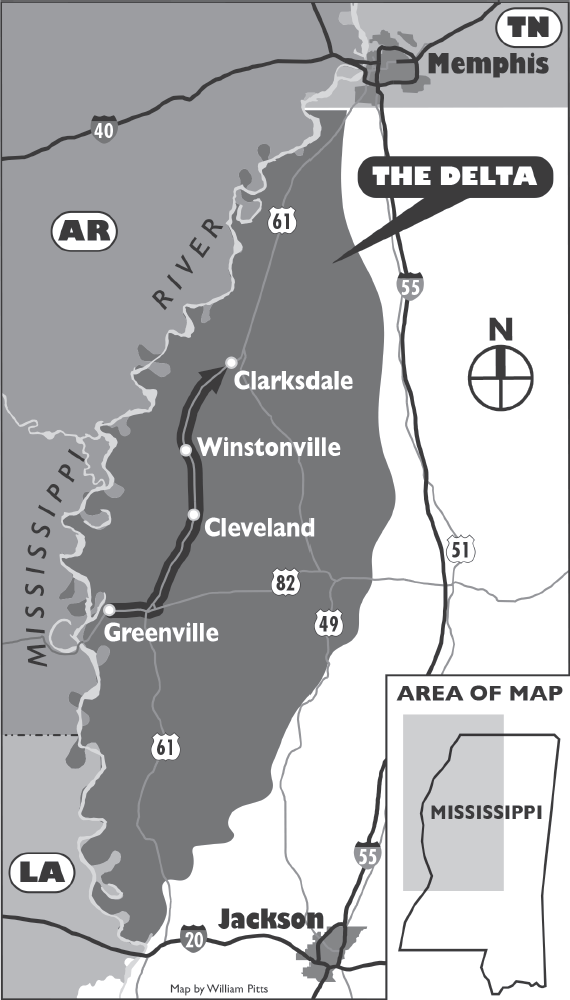

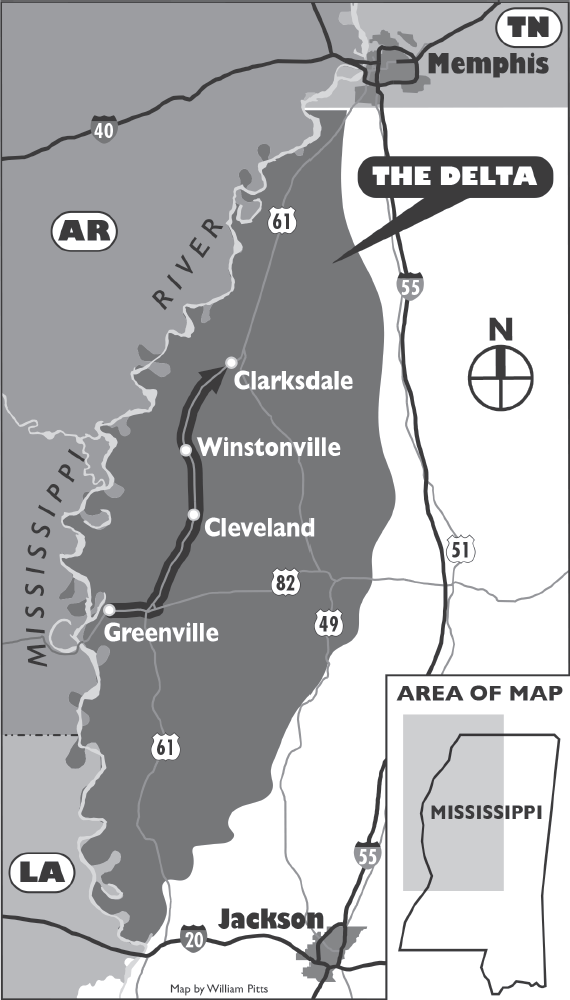

Map of Robert Kennedys route through the Mississippi Delta.

PREFACE

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a son of Americas promise, power, and privilege, knelt in a crumbling shack in 1967 Mississippi, trying to coax a response from a child listless from hunger. After several minutes with little response, the senator, profoundly moved, walked out the back door to speak with reporters. He told them that America had to do better. What he was seeing, as he privately told an aide and a reporter, was worse than anything he had seen before in this country.

As he toured the Mississippi Delta, an impoverished cotton-producing region in the northwest corner of the state, that warm April day in 1967, Kennedy talked with mothers about how they fed their children. He looked in empty refrigerators and asked school children about their breakfast. The depths of deprivation he found in Mississippi stunned both Kennedy and, because of the press coverage that inevitably followed him, the nation.

During the forty-eight hours or so that Kennedy spent traveling through Mississippi, however, he did more than just encounter hungry children. He sparred with powerful members of the states political elite, officials who resented money spent on early childhood education for poor black children. He toured job training programs and Head Start classrooms. He gave two impromptu speeches to wildly enthusiastic college studentsone on a mostly white campus, and the other at an African American college. He dined with civil rights leaders, journalists, liberal business leaders, and educators at a lovely suburban home. In addition to all of that, he shared a drink by a hotel pool, talked New York politics and baseball with a local reporter, and even took a nap in the guest bedroom of a Jackson pediatrician.

Kennedy arrived in Mississippi at a pivotal point in American history. After the speeches, protests, legal showdowns, and violence of the 1950s and early 1960s, Congress had finally responded with sweeping changes. There were new civil rights laws, enhanced protections for voting rights, and a War on Poverty.

Furthermore, the war in Vietnam was going badly, and Americans were beginning to realize it, even if they were still deeply divided on what to do about it. Just a month before he arrived in Mississippi, Kennedy had stirred controversy by breaking with President Lyndon Johnson and offering a three-point plan to end the fighting in North Vietnam. Then, a week before Kennedy toured the Delta, Martin Luther King Jr. earned his own part of the controversy when he publicly criticized the war for killing the nations young people and syphoning money away from programs that helped the poor. A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death, King told the congregation at Riverside Church in New York.

Kennedys visit to Mississippi in 1967 provides a useful lens to examine the impact of these waves of change. His visit was a catalyst that drew out the extremes of Mississippis culture at the time. In Jackson, members of the Ku Klux Klan met him at the airport, carrying signs castigating him for his position on Vietnam and distributing flyers predicting his death. They were only echoing the hatred of Kennedy that many white Mississippians harbored because of his role as attorney general in the integration of the University of Mississippi, and other conflicts over civil rights in the state.

However, both black and white civil rights advocates on the frontline in Mississippi were unimpressed with his record. Many of them had struggled through life-threatening violence with little or no help from the Kennedy administrations Department of Justice. They viewed Kennedy as a ruthless political dealmaker who put too much priority on placating powerful southern politicians in Congress.

In contrast, Kennedy and his brother were heroes to many of the ordinary African American residents of the state. In fact, just about forty-eight hours after Kennedy landed in the state to the belligerent shouts of the Ku Klux Klan, hundreds of African Americans in Clarksdale cheered him and, as one journalist who was traveling with him recalled, reached up to him like they were trying to touch the robes of Jesus Christ at his last stop in Mississippi.

Hints of other changes were in the Mississippi air as well. The day before Kennedy arrived, the daughter of Ronald Reagan, Californias charismatic new conservative governor, was the guest of honor at a luncheon in Greenville designed to build support for Phyllis Schlafly as the conservative candidate for president of the National Federation of Republican Women. Clarke Reed, the Greenville businessman, who hosted Maureen Reagan Sills had little interest in Kennedys visit. Instead, Reed had long been intent on building a strong, business-minded Republican Party in the state to offset the unmitigated power of the Democratic Party that had ruled the solid South for so long.

The day Kennedy left Jackson for the Mississippi Delta, Stokely Carmichael spoke in the same chapel at Tougaloo College where Kennedy had talked with students the evening before. Carmichael was a leading voice for a new breed of civil rights activist focused on black power. His passionate, uncompromising rhetoric was thrilling African American students and rattling the establishment across the South in the spring of 1967. He arrived in Jackson just days after a riot that broke out in Nashville following his speech at Vanderbilt University, and he left Jackson with a state lawmaker calling for charges of treason against him.

Next page