THEODORE H. WHITE

THE

MAKING OF

THE PRESIDENT

1968

FOR

JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY

AND

ROBERT FRANCIS KENNEDY

Saul and Jonathan, sweet and

beloved in their lives; nor in their

death were they divided; swifter

were they than eagles, braver than

lions.

DAVID S LAMENT, SAMUEL II : 1

CONTENTS

Behold men, as it were, in an underground cavelike dwelling, having its entrance open towards the light, which extends through the whole cave. Within it, persons, who from childhood on, have had chains on their legs and their necks; so they can look forward only, but not turn their heads around because of the chains, their light coming from a fire that burns above, far off and behind them.

And between the fire and those in chains is a road above, alongside which one may see a little wall built, just as the stages of magicians are built before the people in whose presence they show their tricks.

Behold then, beneath and behind this little wall, men carrying all sorts of machines rising above the wall; and statues of men and other animals, some of the bearers probably speaking, others proceeding in silence.

Think you that such as those who live in the cave would have seen anything else of themselves, or of one another, except the shadows that fall from the fire on the opposite side of the cave?

And if the prison had an echo on its opposite side, when any person present were to speak, think you they would imagine anything else addressed to them except by the shadow before them?

Such persons would deem truth to be nothing else but the shadows of exhibitions.

PLATO: THE REPUBLIC, BOOK VII, 2

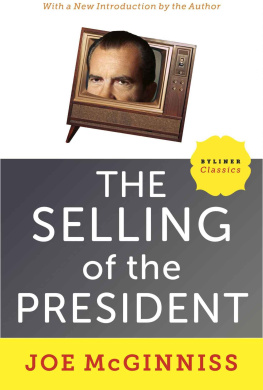

In The Making of the President 1968, Theodore H. White tackles not just a political campaign but an American cultural icon. The year 1968even these four decades latercontinues to both haunt and rouse this countrys spirit.

By one accounting, the years events are tragic, pure and simple. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is assassinated in Memphis. Robert F. Kennedy is gunned down in Los Angeles. Chicago, host to a national political convention, becomes the platform for a nationally televised riot. The country holds a presidential race among Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, and third-party candidate George Wallace, with much of the country wishing they had some other choice.

But to those who lived that year, especially on a college campus, 1968 looms even now as the most exciting political year of their lives. It was the year when the Sixties reached its peak, when generational rebellion was at its most exuberant, and when kids got clean for Gene and rooted for Eugene McCarthy or Robert Kennedy with all the excitement they could muster.

The Sixties, now generally accepted, bore only a rough correspondence with the actual decade. They began in the afternoon in Texas in November 1963 and ended in the evening when Richard Nixon was forced to resign from his presidency in August 1974. The year 1968 was both the midpoint of this eleven-year stretch and its fulcrum.

Like that first American year, 1776, it was the culmination of what had come before. Thanks to Teddy White, we get to see 1968 in all its power; it is a worthy third episode in his quadrennial look at how this country makes up its mind.

In The Making of the President I960, Theodore White had chronicled young John F. Kennedys rousing charge toward the U.S. presidency. The 1964 campaign, which White again covered, held the mood of an Irish wake. The names on the ballot were Lyndon B. Johnson and Barry Goldwater, but in the grim aftermath of assassination, the most profound national emotion was grief. The country wanted Jack Kennedy back. When Lyndon Johnson said, Let us continue, the electorate agreed.

By 1968, however, few wanted anything of the sort. Five years after Dallas, the countrys mood had darkened. With a half million troops in Vietnam, America was a land divided: hawk v. dove, town v. gown, long-haired against clean-cut, father against son.

In The Making of the President 1968, White captures all this and more. What grabs the reader today is how historically busy the times wereeven more than we remember. Weve forgotten the fascination with which this country and the world enjoyed the anticipated American landing on the moon. What have not lost their currency are the words that appear here from our then-ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson. In a speech given a week before he died in 1965, he spoke about the need to protect life on this planeta message that carries equal power in our twenty-first-century discussion of global warming and climate change.

We travel together, passengers on a little space ship, dependent on its vulnerable supply of air and soil; all committed for our safety to its security and peace, preserved from annihilation only by the care, the work, and I will say the love we give our fragile craft.

A page later, White reminds us that the bitter national debates of our time are mild compared to those of the late 1960s, when rage over Vietnam, pitting hardhats against student protesters, was more than matched by urban rage at racial injustice. Hate was to this period, as White observes, what fear was to the early Great Depression.

The great political enigma of 1968, which looms as more anomalous as the years go on, was the dramatic electoral comeback of Richard Nixon. Defeated narrowly by John F. Kennedy in 1960, then badly two years later in his ill-considered run for California governor, Nixon was, in Whites retelling, as moribund as Ebenezer Scrooges departed partner, Jacob Marley.

No doubt whatsoever about that, White writes. Political clerks, clergymen, undertakers, and mourners had all signed the register. Nixon was as dead as a doornail.

But that was before 1968, this incredible year to which White has devoted so much mind and heart to explaining. The chain of events that led the American people to Nixon began in late January 1968 with the Tet offensive in South Vietnam, a vastly coordinated attack by Viet Cong and main-force North Vietnamese troops on the countrys provincial capitals. The attack, President Johnson would tell this country, was a military failure resulting in tens of thousands of enemy dead. The only positive benefit, he admitted in a press conference, would be a psychological victory. What he didnt admitwhat he didnt know to admitwas that he, Lyndon B. Johnson, would be its prime casualty.

White explains Johnsons failure as his inability to see how the Tet offensive would shake confidence that the Vietnam war could be brought to a successful end. It was not just the conflicts cost in lives, which we saw counted each night on the evening news, but the growing sense that the war was unwinnable.

A president can trust no one and no theology, except his own sense of history; all the instruments of government must be subordinate to this feeling of his for history: and when this supreme guidance is lacking, the instruments themselves are useless.

It so happened, however, that by the beginning of the year 1968 the instruments of American government had failed American purpose as never before. This was what had become obvious to the American people at the Tet offensivestaining the vast majority with that morbid, unhappy mood which lasted until election night.

For several months in 1968, and for millions of Americans, especially those of college age, this morbid, unhappy mood was relieved by the most bracing political experience of their lives.

Next page