A LSO BY B ROUGHTON C OBURN

Nepali Aama: Life Lessons of a Himalayan Woman

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS TRADE PAPERBACK EDITION, APRIL 1996

Copyright 1995 by Broughton Coburn

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American

Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States

by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc.,

New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random

House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published

in hardcover in the United States by Anchor Books in 1995.

A NCHOR B OOKS and colophon are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

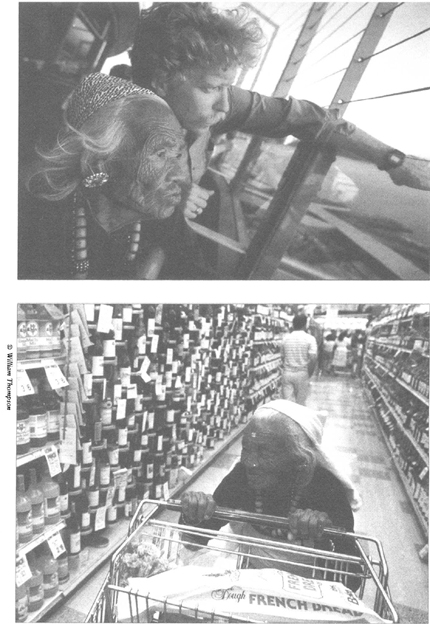

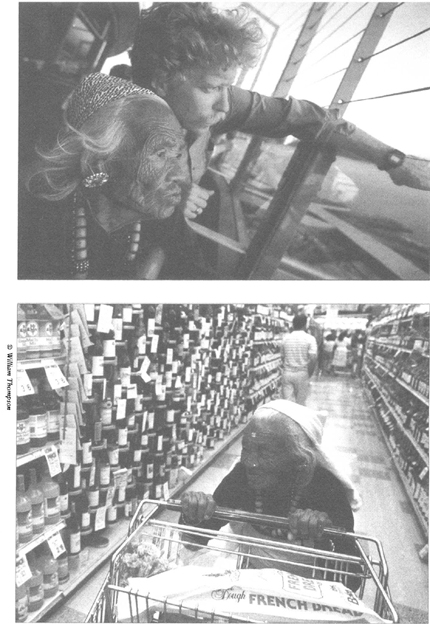

All photos except top photo on (William

Thompson), (Russell

Johnson) are by the author and are reprinted by

permission of the author.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover

edition as follows:

Coburn, Broughton, 1951

Aama in America : a pilgrimage of the heart /

Broughton Coburn.

1st ed.

p. cm.

1. United StatesSocial life and customs1971

2. United StatesDescription and travel. 3. Gurung,

Vishnu MayaJourneysUnited States. 4. Nepalese

TravelUnited States. I. Title.

E169.04.C64 1995

917.30492dc20

94-38806

eISBN: 978-0-307-78783-5

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

For Alex and Lu.

In the most general terms a pilgrimage represents a persons journey from the world of the profane, or ordinary, to the world of the sacred, and as such is often marked by the characteristics of a rite of passage in which the participant undergoes a process of separation, threshold, and incorporation.

David R. Kinsey, Hinduism

Har Om, please bless me and my dharma son and daughter-in-law and the drivers of the airplane and all the people joining us on this long journey, for I am going in ignorance of what will befall me.

Aama

Acknowledgments

The extraordinary and unanticipated generosity of Vishnu Maya Gurung (Aama), her relatives, and the Gurung people of their village in the hills of Syangja District, Nepal, formed the early inspiration for this book. To return their rich hospitality and friendship would be difficult. Taking Aama to America could represent only a perfunctory thank you.

Before my girlfriend Didi and I left Nepal with Aama for the United States, I had thought of documenting Aamas reactions to America. Privately, I worried that Aama might register little beyond shock and displeasure at the fleeting, contorted circus acts of our nation. Initially Didi and I had only the skeleton of an agenda, and Aama had none. The West Coast was our sole destination, and we were prepared at any point to return to Nepal with Aama, if she desired. We never imagined this would occur after three months, twelve thousand car miles, and the kind of physical and mental obstacles that Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims have come to expect.

We had elected ourselvesor, rather, I had chosen myself and dragged Didi alongas Aamas driver and attendant. Tethered together like Apollo astronauts in the front seat of a station wagon, the three of us swept over the continent. Lying beneath the uniform, commercial, man-made epidermis of our country, Aama found a culture and landscape that was alive and sacred, and she steered us toward it.

Didi and I ended up taking a backseat to Aamas search, sharing in her discovery and her frustration, witnessing her ancient worldview draw up short before our modern one, and then leap over it. I had lived in Aamas home and village long enough to sense her moods, but America constantly challenged me to bridge the sizable cultural and age gaps, to unravel her sometimes obscure associations, and to fulfill her expectations about Americans as people.

Eventually I gave up trying to define or interpret what Aama was seeing clearly for herself, and simply began to record. I missed a lot. I assumed that the camera, pen, and tape machine would document it all adequately. But what meets the eye or ear only selectively emerges as thought and analysis. Memory, seasoned by time, will often recall events with greater depth than the best efforts of description during their original occurrences. The journey had become a process, and that process a catalystfor uncovering more than we had bargained for.

I had presumed that including Aama on our road trip would cost only nominally more than her plane ticket to the States. We continued to live in our accustomed low-budget manner, while I watched my bank balance leak away. I shot 380 rolls of film with three older-model Nikon single-lens reflex cameras, and recorded more than fifty hours of conversation on a series of cheap microcassette recorders that each ran at different speeds.

I am indebted to Aamas daughter, Sun Maya Gurung. To those who generously advised, guided, and encouraged us during our journey across the United States, and to those who extended gifts and hospitality, I express my sincere gratitude. The list is too long to include them all, but Ill begin by thanking Randy Bell, Chad and Darlene Broughton, Anita Byock, Kanak Dixit, Ronnie Egan, Deborah Flanders, Lisette Gunther and the late Kurt Gunther, Nar Bahadur and Kushi Gurung, Raine Hall, the Hanuman Ashram of Taos, Nancy Hawver, Bill Kite, Jeff Long, Efale McFarland, Tom McMackin, Don and Kareen Messerschmidt, the Milford Colony of Hutterian Brethren, Stephanie and Michael Nadeau, Kathleen Peterson, Cecilia Pleshakov, Chuck and Joan Pratt, Tom Pritzker, Geoff and Janet Rockwell, Dan Rotrosen and Liz Dugan, David Sassoon, David Shlim, Larry Shlim, Florence and Lawrence Singer, Minu Singh, Todd Stuart, Christian Swenson and Abigail Halperin, the people of the Taos Pueblo, Caroline Tawangyma, Hilda and the late Austin Two Moons, Mary Ellen Valyo, Thekla von Hagke, Nevada Wier, Maria Wilhelm, and Richard Wiswall. I apologize to those Ive missed.

While the manuscript and photographs were being prepared, the following friends offered invaluable assistance: Scott Andrews, Dick Dorworth, John Frederick, Paul Gallagher, Jeff Greenwald, Mary Gurdy, Ashok Gurung, Chandra Prasad Gurung, Dil Bahadur Gurung, Jagman Gurung, Nancy Jo Johnson, Ella Laub, Lobsang Lhalungpa, Hemanta and Sushma Mishra, Laura Nolan, Stephen Olsson, Gajendra Nath Regmi, Jamuna Gurung Shrestha, Eric Valli, and Melissa Walia. I would like to specially thank Misty Haley, Sandra Lambert, and Dotty and Palmer Smith for their careful proofreading, advice, warmth, and refuge.

My agent, Sarah Lazin, provided an expert balance of criticism and encouragement. She recognized the end of the story at the time it occurredwell after Aama had returned to Nepal and before it had been written down. The lessons that ordeals teach us sometimes are learned only later, and unexpectedly.

Charlie Conrad, my editor at Anchor Books, followed the book into its present form with faith and patience; Jon Furay and Kevin Lang tended to important details, and did much careful, tedious footwork.

In particular, I want to thank my parents, Alex and Lunette Coburn, for their love, assistance, and good cheer. Also, many thanks to Doug and Karen Chadwick, David Larkin and Susan Cochran, Ann and Greg Lyle, William Thompson and Tori Withington, Genna Thunder, Barbara Thunder, and Betsy Withington, who gladly offered their homes and hearts well beyond any conventional welcome period. They, too, are like family.