Contents

Foreword

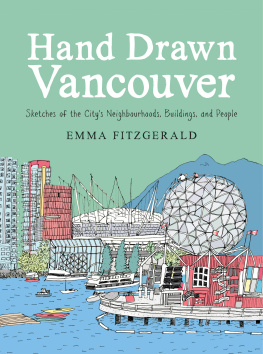

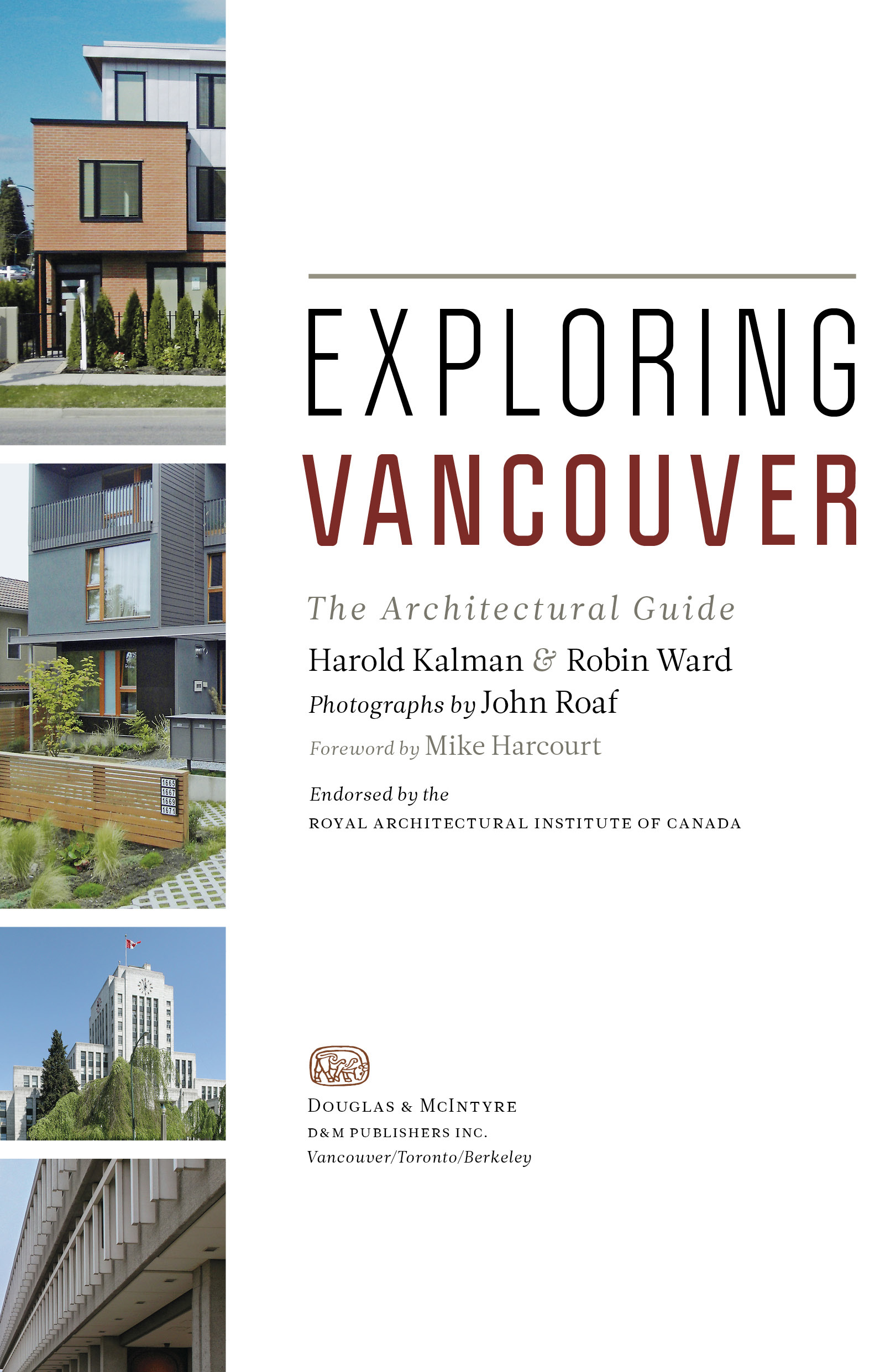

VANCOUVERITES have always known that they live in a unique and stunning setting, surrounded by the sea, mountains and Fraser River, along with lush forests, parks and foreshores brimming with varied flora and fauna. Creating a built environment that complements and responds to this richness has been a challenge for architects and city plannersa process thats seen growing pains and close calls along the way. In Exploring Vancouver , Harold Kalman, Robin Ward and John Roaf show how this fascinating history has been encapsulated in the young citys diverse architecture and how bold, visionary decisions have prevailed, allowing Vancouver to take its place at the forefront of livability and urban sustainability. Vancouver may not be the first city to come to mind when one considers the worlds iconic structures, but to study its architecture is to look into both its past and its future. As this book deftly shows, the mix of neighbourhoods, from historic Gastown and Chinatown to revitalized False Creek and ever-changing West End, and the mix of buildings within those neighbourhoods, are a consequence of policy decisions. These include triumphslike the creation of Stanley Park, requested of the federal government by Vancouvers very first city councilas well as misstepssuch as the short-sighted building codes that led to the leaky condo crisis of the 1990s.

One such disaster was narrowly avoided: in the 1960s, when I was a long-haired (sigh!) storefront lawyer, I worked with Chinatown merchants, Strathcona residents and other citizens to fight a proposed freeway that would have destroyed some of Vancouvers most characteristic neighbourhoodsfrom Gastown and Chinatown to Strathcona, the Grandview Woodlands and Hastings-Sunriseand wiped out the waterfront as we know it. Our campaign to stop the freeway came to define what Vancouverites value. Today Vancouver is the only major city in North America without a major freeway going through it; our central city area has 140,000 residents, three-quarters of whom take transit, cycle, walk or telecommute instead of driving a car.

When I became mayor, my tenure was dominated by planning for Expo 86, and we successfully turned a potential $600 million deficit (the same size per capita as the Montreal 1976 Olympic deficit) into a boom in tourism and trade and a big success for Vancouvers citizens. In the lead-up to the event, we built important permanent infrastructure, such as Canada Place, Science World, a redeveloped north shore of False Creek and the Expo SkyTrain line. More recently, Vancouver built upon that experience of hosting the world, and the 2010 Olympic Winter Games gained us the expanded Trade and Convention Centre, the Canada Line, as well as new and rennovated sports facilities that will serve generations to come.

In my years of public service, Ive witnessed the city evolve to embrace a planning philosophy that has come to be known as Vancouverismmulti-use, high-density core areas; a transit-focused transportation system; and thoughtful urban design that serves our spectacular natural setting and our vibrant, multicultural populationnow a model for urban centres the world over. Over the coming decades, Vancouver has the opportunity to become a mecca for urban sustainability as we grapple with population growth, global warming and peak oil. Exploring Vancouver points to these challenges, while celebrating the citys history and its achievements, and I look forward to seeing the rich architectural and urban legacy that this progress will bring.

MIKE HARCOURT

Introduction

The magic city which grew out of a forest whose trees were taller than our monumental buildings.

MAJOR J.S. MATTHEWS (18781970), Vancouvers first city archivist

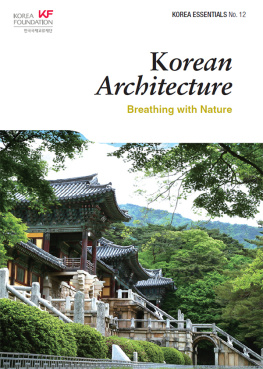

VANCOUVER was incorporated on April 6, 1886. Two months later, the Great Fire destroyed the original logging settlement, established after European maritime exploration in the late eighteenth century revealed abundant natural resources to a wider world. The city arose from that calamitous foundation, evolving as a multicultural metropolis, envied as one of the worlds most livable and for its glorious natural setting. It is not generally known for its architecture.

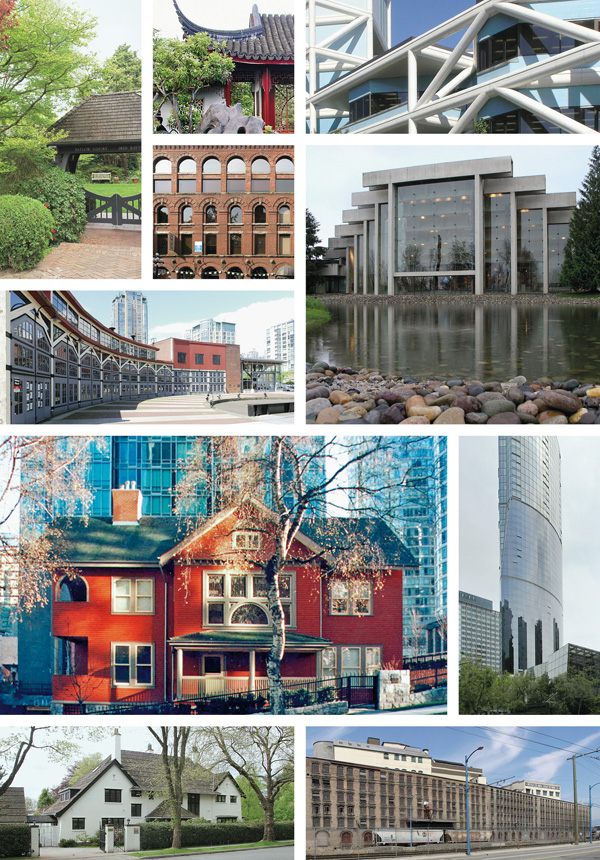

Exploring Vancouver reveals the architecture and urbanism of the city, its history and the people and the society that made it. The story of the citys development is one of creation and reinventionby British, Eastern Canadian and American opportunists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, through the post-WWII modernists, to the present crusade for livability and sustainability. The book also looks at a selection of old and new architecture of the municipalities that surround Vancouver.

Early settlers erected sawmills, stores, saloons and churches on First Nations territory. The opening of the transcontinental railway terminus in 1887 diversified the economy and boosted development. During Vancouvers first three-quarters of a century, architecture was mainly institutional or commercial and traditional in approach. Ambitious cultural buildings and innovative design are products of the modern era, when postwar prosperity and confidence shook off the last threads of pioneering and Depression-era austerity and colonial conformity.

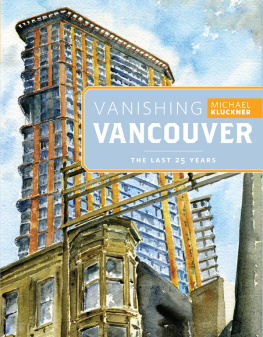

When the previous (third) edition of Exploring Vancouver was published in 1993, the high-spirited, Art Deco Marine Building was still prominent on the waterfront. Today, it is hemmed in by new towers, part of a building boom that was the result of a unique conflation of events, including the sale by the provincial government of the Expo 86 site on False Creek to Hong Kong industrialist Li Ka-shing and the Canadian Pacific Railways redevelopment of Coal Harbour. Consequent planning and construction have seen forests of residential high-rises shoot up on and around the downtown peninsula. New neighbourhoods, particularly False Creek and Coal Harbour, have been built out in a manner admired internationally as Vancouverism, an ideology of dense but civilized urbanism, exported as a template for utopias worldwide. That radical transformation to the cityscape motivated this new edition.

Vancouver is at a turning point, as its citizens face challenges of sustainability in an era of global turmoil and climate change. Architecturefrom basic shelter to iconic public buildingsis fundamental to how we deal with them. Global investment and the increasing population of the city raise issues of suburban sprawl and density, provision of public amenities, transit and the desire to respect the natural setting. Another concern is the loss of industrial land, rezoned for residential use. While the Port of Metro Vancouver is an exception, many industries have relocated to the suburbs near highways. This trend may be reversed because of the rising cost of fuel, and to attract a skilled young workforce that is drawn to city life. Downtown Vancouver is now largely residentialdubbed a resort by some commentatorsas new towers are built and old ones adapted to housing. Green technologies and urban farming present architects with opportunities for mixed-use typologies, and communities and planners the question of unconventional zoning to accommodate them.

Next page