Korean Architecture

Breathing with Nature

KOREA ESSENTIALS No. 12

Korean Architecture

Breathing with Nature

Copyright 2012 by The Korea Foundation

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

First Published in 2012 by Seoul Selection

B1 Korean Publishers Association Bldg., 105-2 Sagan-dong,

Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-190, Korea

Phone: (82-2) 734-9567

Fax: (82-2) 734-9562

Email:

Website: www.seoulselection.com

ISBN: 978-1-62412-047-3

INTRODUCTION

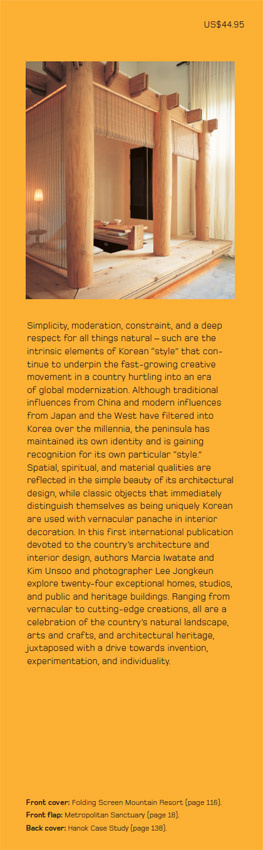

Foreign visitors to Korea today are often struck, above all, by the countrys architectural landscape. Republic of Apartment was the title of one recent work by a French geographer attempting to make sense of the prevalence of the uniform high-rise apartment blocks she found, both in Seoul and in the Korean countryside. A glance lower down, however, and into a few quieter neighborhoods, palaces, Buddhist temples, and pockets of the countryside, reveals a rich heritage of ancient traditional, colonial, modern, and contemporary architecture. Much of Koreas architectural past has been lost or demolished in the recent rush for modernization, but much still remains. This book offers an introduction to Koreas abundant and unique architectural past and present, combining explanations of the principles behind Korean architecture with introductions to some of the countrys finest buildings and structures.

Chapter One sets the scene by explaining some of the ideologies and perspectives at the foundation of Korean architectural tradition. Nature, it becomes clear, was a dominant factor in the combination of philosophic and practical considerations that gave shape to the characteristics found in Koreas iconic wood-framed, tiled structureswhich varied surprisingly little between building types, be it a palace, temple, school, university, administrative building, or private home.

Chapter Two provides an outline of the history of Korean architecture, from the first architectural traces of dugouts and lean-tos to increasingly sophisticated wooden frames and technologies. Major philosophical and ideological influences, especially from Buddhism and Confucianism, become clear. Koreas late 19th century collision with foreign powers had a cataclysmic influence on its architecture: international styles proliferated throughout the country afterward.

Chapter Three offers a brief introduction to the basic elements of Korean traditional architecture, and the hanok, a term used today primarily to refer to houses built based on traditional style wooden frameworks and tiled roofs. The basic construction process, structural anatomy, and materials used are described.

Chapter Four highlights ten of Koreas best-known and most significant traditional buildings, ranging from Buddhist temples and Confucian royal shrines to landscaped literati gardens and Enlightenment-era fortresses. It provides a glimpse of the variety of traditional architecture in Korea and some of the principles that shaped it.

Chapter Five focuses on Koreas early modern architecture, which emerged and developed at a historically traumatic time that culminated in 35 years of colonial domination by Japan but is a crucialand fascinatingperiod in the countrys architectural history. Its scope extends beyond Japans withdrawal from Korea and into the mid-20th century, when Korean architects such as Kim Swoo-geun and Kim Chung-up began to create a contemporary architectural identity for the country.

Architecture, of all the arts, is the one which acts the most slowly, but the most surely, on the soul.

Ernest Dimnet

A geographical treatise from the Joseon Dynasty (13921910), Taengniji (Ecological Guide to Korea) outlines the requirements for identifying an ideal site for human habitation. A propitious site, it says, is one with excellent topography, ecology, wholesomeness, and hills and waters. Topography refers to the layout of the surrounding mountains and rivers; ecology to the things that originate from the ground; wholesomeness to the character of the local inhabitants; and hills and waters to the areas scenic beauty. Of these four factors, three are natural phenomena directly related to the earth. This reflects the extent to which Koreans believed nature influenced the desirability of human habitation; indeed, Koreas traditional architecture is meaningless in isolation from nature.

Although the practice of geomancy that Koreans call pungsu was introduced to Korea from China, where it originated under the name feng shui, it is actually in Korea, rather than in China or Japan, that its influence has been most evident. Mountains and rivers are the most important elements in pungsu. Mountains are needed for harnessing the wind, while rivers constitute sources of water. According to the East Asian perspective, nature is a world of abundant energy, or gi (often known in the West by its Chinese pronunciation, qi), that is constantly moving and changing. The wind transports the energy of the sky to the earth, while water carries the energy of the earth. Thus, a terrain with a proper arrangement of mountains and rivers is the most effective means of harnessing the energy of nature. A site with an abundance of natural energy is propitious, as it is believed that this energy will flow into the people living in a house built there.

Changdeokgung Palace is renowned for its design, which defers to the topography of its terrain.

NATURE: THE MOST FUNDAMENTAL INFLUENCE

The first and most important step in traditional Korean architecture, selecting a building site, involves properly interpreting the topography of the land. Ultimately, the most highly sought architectural sites were those known as baesan imsu, a term describing a setting with a high mountain at the rear to block the wind and a wide field in front with a river flowing through it. Such an area held promises of abundance.

Once the site was selected, the ground was leveled and prepared for the construction of the building. At this stage, the most important factor was determining the direction the building should face. The modern preference for a southern orientation was not an absolute rule. What the building would look out upon was often more important, indicating that psychological perspectives could take precedence over functional considerations. The scene over which a building looked out was called the andae. This was most often a mountain, because mountains are the only natural elements considered to be unchanging and everlasting.

Hahoe Village, with mountains to the north and a river to the south, demonstrates the baesan imsu principle.

Next page