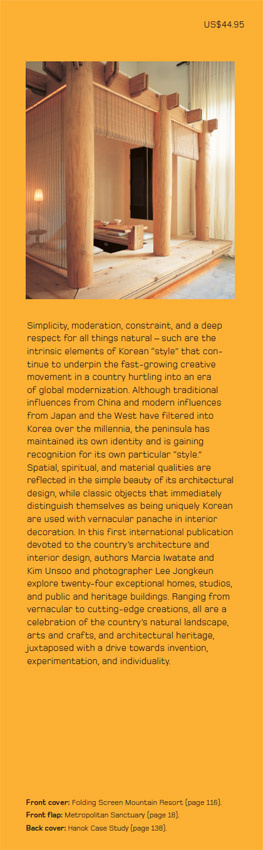

korean aesthetics, modern directions

CLARK E. LLEWELLYN

KOREA STYLE is epitomized by the beauty and humility observed in the offering of a cup of tea with two hands gently folded while lightly grasping the base of a perfectly proportioned white porcelain cup. The guest, in turn, receives the object of tradition and art with two folded hands and a slight nod of the head in appreciation of the respect shown. Korean architecture, interiors, art, and artifacts generate similar signs of appreciation and reverence for their natural world. Coupled with this is the Koreans innate sense of beauty, which extends from the smallest object to the largest and allows them to create not only structures, interiors, and artifacts that are quintessentially Korean but also assimilate those of others so that they attain a Korean character. Such is the essence of Korea style.

As a Westerner first visiting Korea, I misunderstood an architect when he pointed out the natural placement of a stone in front of a residence and said how beautiful it was because it was an old stone. Unwittingly, I asked how old he thought it was in geological time. He did not reply. To understand his meaning and desire to have an old stone, it is necessary to learn something of the teachings of a seonbi , a Korean philosopher from the Yi Dynasty ( AD 13921910), better known today as the Joseon Dynasty, who taught that an old stone or rock represents age, not literal age, but a respect for age respect for parents, teachers, and elders. The old rock has weathered many storms, seen the heat of summer, the bitter cold of winter. It is creased by water and smoothed by wind. It is not polished. It is not unrivalled by Western (or even Chinese and Japanese) standards, but viewed through Korean eyes it is perfect because of its reflection of age, nature, and sense of place.

Since antiquity Koreans have developed this special affinity with nature, an affinity which expresses itself in unmistakably Korean images of pastoral villages tucked between rocky mountains, forests of gnarled pine trees, lush green rice paddies, and walls and paths built with stones in their natural forms. Mountains form a pocket on the north and the Han River forms a soft, flowing line on the south of the 600-year-old capital city of Seoul. Early Neolithic remains found among the dolmens were placed in harmony with the natural landscape. During the Ancient Period ( AD 200600), houses evolved from pit dwellings to structures with earthen walls and thatched roofs, then to log structures, and finally to structures which showed the first evidence of the unique Korean raised floor panel heating system called ondol . It is believed that this heating system, which was to become so widespread in the seventeenth century, was never implemented in China because tables and chairs were used instead, and although floor seating did travel to Japan from Korea, the Japanese did not employ under-floor heating either. This technological innovation is still embraced by contemporary residential architecture for its energy efficiency, even distribution of heat, and elimination of the need for diffusers, radiators, and other visible mechanical devices. Under-floor radiant heating has since spread widely in the West and Japan.

The Three Kingdoms of the Ancient Period were brought together under the United Silla (seventh to tenth centuries), which absorbed the mature culture of the Tang Dynasty in China while developing a unique cultural identity. Buddhism and its art and architecture flourished during this period. In AD 918, the last king of Silla offered his kingdom to the ruler of Goguryeo, which took the name of Goryeo (Korea to Westerners). The Goryeo Dynasty ( AD 9181392) brought about a state embracing both Buddhism and Confucianism, and developed the ancient capital city of Songdo (now Gaeseong) in North Korea. The non-axial arrangement of the city responded to the natural contours of the mountainous landscape and led to the proclamation that nature should prevail over human design. Geomancy, a method of divination for locating favorable sites for cities, residences, and other activities, was proclaimed as a leading principle of design. The basic theory stems from the belief that the earth is the producer of all things and the energy of the earth in each site exercises a decisive influence over those who utilize the land. It is believed that when heaven and earth are in harmony, the inner forces will spring forth and the outer energies will grow, thereby producing wind and water; interestingly, the Korean word for geomancy, pungsu , literally means wind and water. Principles of geomancy have been used to great effect in the orientation and design of Bedrock Manor (page 166) by Kim Kai Chun, and with the use of water elements, a leitmotif common to many of the residences in this book, notably those designed by Cho Byoungsoo, Choi Du Nam, and Kim Choon.

Guests to Fashion Designers Muse (page 50) enjoy lounging around the massive rough-edged granite slab table in the double-height living room, seated on floor cushions with accompanying cubicle armrests.

All windows capture the sensuous outlines of the deep eaves, which, combined with the interplay of columns and beams inside, heighten the sensation of being inside a traditional Korean house (hanok) in Reincarnation of a Bygone Era (page 190).

The basis of the architecture and art that we see today, and which forms much of contemporary Korea style, was established during the Yi (Joseon) Dynasty, which supported the ideals and practices of Neo-Confucianism. The principles strongly influencing design at this time included dedication to simplicity, moderation, respect, and restraint. Seonbi also communicated the importance of writing, painting, meditation, and a minimalist approach to life which valued deep respect for all things natural. Pottery was simple yet exquisitely proportioned. Colors and decoration were minimized in both art and architecture, thus exposing the simplicity and purity of the materials. Simplistic perfection of man was sought as a counterpoint to the perfection of natures complexities to achieve simplicity. In its ideal state, Korea style values not only age and nature but also a commitment to minimalism as a way of life. These principles are employed to perfection in many of the design elements featured in this book, notably in the buildings designed by Cho Byoungsoo, Kim Incheurl, and Seung H-Sang.

Confucianism engendered a deep respect for all things natural, in particular for what their natural state might have been like without the intervention of man. This natural state found beauty in stones left unpolished, wood left unfinished, landscapes left untouched, and plants growing without stylistic shaping. The Korean culture discovered aesthetic and moral value within materials exposed to and thus altered by the natural elements. The sun bleaches and dries wood, the wind reshapes and textures both wood and stone, rain flows across surfaces gradually etching its path into the materials. Heat and cold expand and contract materials, reinforcing the aging process. All of these effects are evident in the highly esteemed vernacular complex, Masterpiece of Confucian Architecture (page 204).

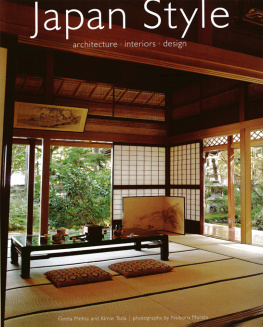

The Korean concept of space has also been influential in its architecture and interior design. Historically, the spatial perception of Koreans differs dramatically from that of Westerners. When early Westerners first viewed traditional Korean landscape paintings and drawings, they found them flat and lacking in depth, shading, and realism. The Koreans, on the other hand, were astonished that Western landscapes looked so realistic, like mirror images, and were devoid of expressive brushwork and imagination. Unlike in the West, the function of traditional landscape painting in Korea was to act as a substitute for nature, allowing the viewer to wander imaginatively. The painting was meant to surround the viewer and provide no viewing point or pure perspective. This same principle can be observed in landscapes, courtyards, and other outdoor spaces surrounding buildings throughout Korea, and partly explains the importance to the Koreans of having a view, especially one facing a mountain. Likewise, while the Japanese developed Zen gardens with purity and symbolism, the Korean culture continued to embrace natural expressions and the outdoors with much less formality. Trees, grass, and natural gardens are preferred to manicured and artificially developed landscapes. Grass, which has been browned by winter and the lack of water is considered more natural, and thus more beautiful, than the arranged perfection of raked sand. Trees, which reflect the effects of weather and time, are held to be more beautiful than a tortured bonsai.