Grateful thanks are due to all those who helped in any way with this book and particularly the following: Amanda Bennett and the staff at the Priaulx Library in St Peter Port; Stephen Collas at the Guille Alls Library in St Peter Port; Alderney Museum; Guernsey Press , especially Di Digard for her unfailing encouragement and sense of humour; States Archive Service in St Peter Port; Rupert Harding of Pen & Sword Publishing for his help and support; Citizens Advice Bureau.

Bibliography

Ahier, Philippe. Letters on the case of A Crying Evil (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. IX, no. 7, 1901)

Anon. Escape from Castle Cornet (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. I, no. 2, 1830)

Anon. Explosion at Castle Cornet (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. I, no. 2, 1830)

Bonnard, Brian. Island of Dread (Guernsey Press, 1983)

Bonnard, Brian. Out and About in Alderney (Guernsey Press, 1995)

Bouverie, Fred W G. The Eleventh Hour (1854)

Bunting, Madeleine. A Model Occupation (Pimlico, 2004)

Cachemaille, J L V. The Island of Sark (1874; rev. Laura Hale 1928)

Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series 1654 (PRO)

Carey, Edith. Channel Island Folklore (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. III, no. 2, 1909)

Cliff, Capt. W H. Jethou: History, Flora, Fauna and Guide (Guernsey Press, 1960)

Dalmau, John. Slave Worker (Jersey 1946/7)

DeGaris, Marie. Folklore of Guernsey (La Socit Guernesiaise, 1986)

Eggert, Harald. The Channel Islands (Robert Hale, 1998)

Findlay, A G. Channel Islands (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. VIII, no. 4, 1873)

Gazette de Guernsey 1808

Girard, Peter. Guernsey (Guernsey Press, 1986)

Guerin, Lieut. Col. T W M de. Guernsey Society of Natural Science (Guernsey Pamphlets, vol. XVIII, no. 1, 1921)

Guernsey Press (various dates 1900 14 and 1945)

Guernsey Star (various dates 1820 1914)

Guernsey State Archives (1942)

Hawkes, Ken. Sark (David & Charles, 1995 rev. edn)

Hugo, G W L J. Guernsey As It Used To Be ( c .1875)

Johnston, Peter. A Short History of Guernsey (Guernsey Press, 1994)

Kalamis, Catherine. Hidden Treasures of Herm (Herm, 1996)

Lamprire, Raoul. History of the Channel Islands (Robert Hale, 1974)

Le Huray, C P. The Queens Channel Islands: the Bailiwick of Guernsey (Hodder and Stoughton, 1952)

Lihou Priory (Transactions of La Socit Guernesiaise, 1912)

Manchester Guardian . Report of an investigation into the murder of 1000 1200 Jews and Russians on Alderney (19 May 1945)

Marr, James. The History of Guernsey (Guernsey Press, 1982)

McCulloch, Sir Edgar. Guernsey Folklore ( c .1919)

Moullin, J E (ed.). Guernsey Ways (Guernsey Society and Guernsey Press c .1967)

Pantcheff, Captain T X F. Alderney, Fortress Island: the Germans in Alderney (Phillimore, 1981)

Redstone Guide to Guernsey (1848)

Sanders, Paul. The British Channel Islands under German Occupation (Socit Jersiaise, 2005)

Tabb, Peter. A Peculiar Occupation (Ian Allan, 2005)

The Times . Report of an investigation into the murder of 1000 1200 Jews and Russians on Alderney (19 May 1945)

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of the Guernsey Bailiwick

G uernsey has not always been an island. During the last Ice Age, ten thousand years ago, Guernsey and Herm were joined together as a single island and there was a land bridge linking this island to Alderney and from there to the French mainland. As the ice melted and sea levels rose the land links were severed. Guernsey and Herm, however, have only been separated for a millennium or more. The pattern is similar to what happened with the Isles of Scilly which lie off Cornwall; and like the Isles of Scilly, Guernsey too is still a drowning land. That much is obvious at low tide on the west coast where the naked eye can easily pick out the original shorelines at Rocquaine, Perelle, Vazon and Cobo. Around Vazon submerged peat remains indicate the remnants of woodlands near Fort Hommet and the prehistoric farm site at Albecq.

The settlers on the west coast were not the earliest settlers. Les Fouaillages at LAncresse in the north of the island belonged to the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of 5000 BC before being settled later by Neolithic farming folk. Later Les Fouaillages became a ritual and burial site for over 2,500 years before reverting to farming use, for which the fertile ground that lay on the edge of alder, elm, oak and hazel woodlands was ideal. These later inhabitants left behind their pottery, loom weights and arrowheads. The Channel Islands formed part of the ritual landscape which covered Western Europe during the late Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. This landscape was characterized by stone circles, menhirs, dolmens, cursii (earthen banks linking ritual features), cairns, and sometimes ritual hearths. The best example of a dolmen on Guernsey is the passage grave at Le Dhus near Bordeaux in Vale. There is a Guardian figure carved on one of the capstones. At Les Fouaillages a house of the dead was built among the earlier tombs around 2500 BC. Seven hundred years later the Beaker People (named after the distinctive pottery drinking beakers which they made) arrived from the Iberian Peninsula (probably from the area now known as Portugal). There is shipwreck and amphorae evidence that 2,000 years later there was still a trading connection with the Iberian Peninsula. LAncresse Common, together with its rich inheritance of prehistoric features, was covered with blown sand sometime during the 800s, a period when the weather was so exceptionally stormy that Hugh Dorndighe, an early ninth-century Irish king, wrote of it in his diary.

However it was the Iron Age Celts who made the biggest impact on Guernsey, and their influence still survives today. Although their culture (in two phases known as Hallstatt and La Tne) is said to have originated in the Austrian salt-mining villages during the seventh century BC, the people were the descendants of a migration which had begun around 1000 BC in south-west Anatolia (modern Turkey) and swept northwards and westwards across Europe. Today there are said to be five remaining Celtic kingdoms: Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and Britanny. Britanny lies adjacent to Normandy on the western coast of France and is little further away from the Channel Islands than the Scillies are from Cornwall. Islands held a fascination for the Celts, who revered water, and sometimes in Celtic mythology the Celtic otherworld has been described as the islands far across and sometimes under the Western ocean. Drowning islands: a description which fits the Isles of Scilly as well as the Channel Islands, and indeed the two groups of islands have much Celtic folklore in common.

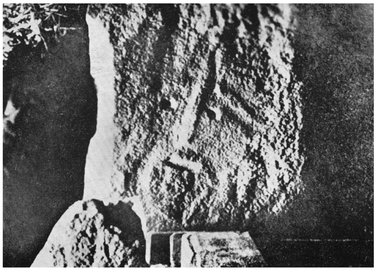

The Guardian of Le Dhus dolmen, c .1910. Authors collection

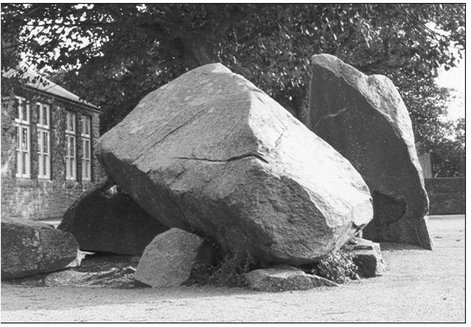

La Roque qui Sonne, c .1950. Standing stone in St Sampson a menhir which characterized the ritual landscape of Bronze Age Guernsey. Reproduced by kind permission of the Priaulx Library, St Peter Port, Guernsey

The Celts were a passionate, vibrant, artistic people who brought their iron-working skills to Guernsey with them. There are several Celtic (or Iron Age) sites on the island. They worshipped a mother goddess, believing the mother to be the giver of life, and the trinity of fertility (birth, death, rebirth) based on the agricultural calendar. Their main festivals were: Imbolc (Festival of the Lambs on 1 February); Beltane (May Day, 1 May); Lughnasadh (Harvest Thanksgiving on 1 August); and Samhain (Old Years Eve, 31 October; their New Years Day being 1 November). There are two statue menhirs of the mother goddess on Guernsey; each some 1.5 metres tall. One stands at the lych gate to St Martins Church; the other in Cstel churchyard. There are three phases to the Celtic mother goddess: maiden (innocence); mother (fruitful bearer of children); hag (old wise woman). Though damaged by over-zealous Christian ministers in past centuries, the prominence of the breasts on the statues probably indicates that they represented the second phase, of the mother. It was customary to leave offerings at the mothers feet. Even today, at the old Celtic festival of Beltane, bunches of flowers are laid at the feet of both mother goddess statues and sometimes garlands of flowers are placed on their heads. In 1921 Lieutenant Colonel T W M de Guerin drew up a list of over 150 dolmens, menhirs, sacred rocks and holy wells which still existed scattered around Guernsey. Offerings were, and in some cases still are, placed beside many of them on certain days of the year.