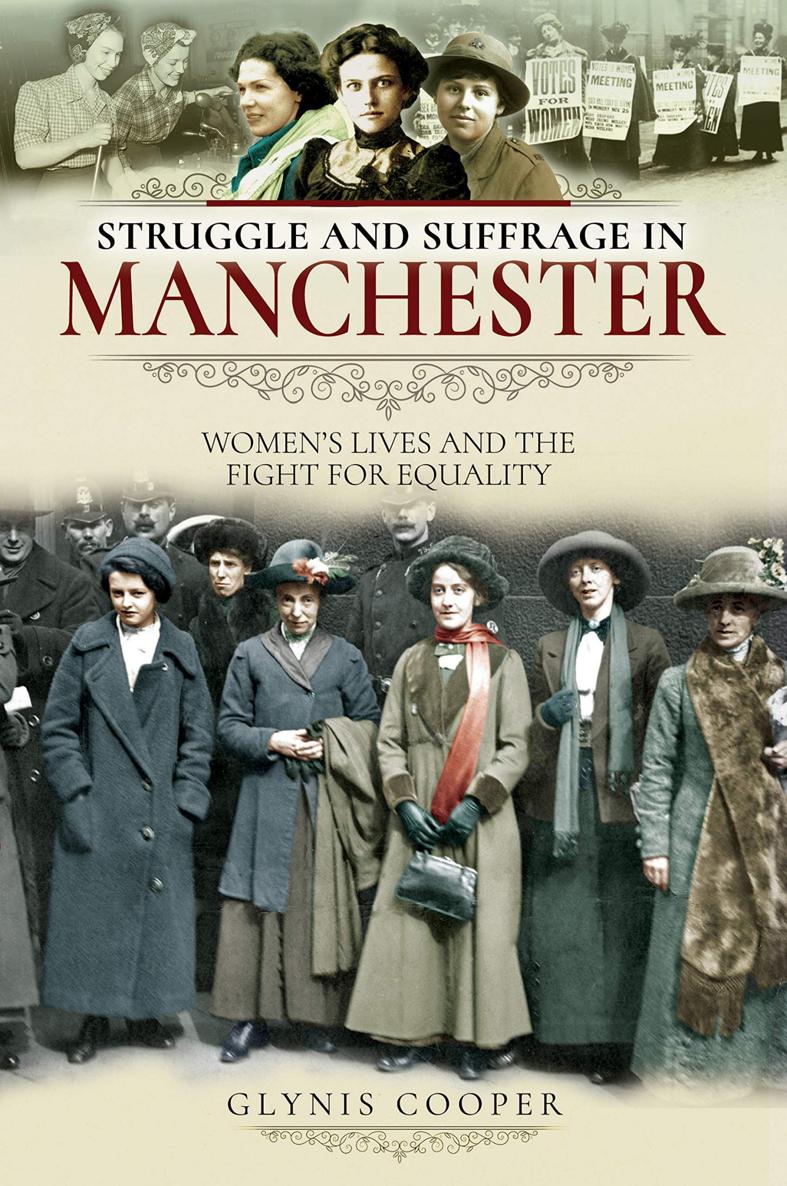

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Glynis Cooper, 2018

ISBN 978 1 52671 2 066

eISBN 978 1 52671 2 080

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52671 2 073

The right of Glynis Cooper to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

The Victorian period, despite having a queen on the throne for sixty-four years, proved to be one of the most repressive periods in British history for women. As queen, of course, Victoria would be used to having her requests obeyed and her needs provided for, but she appeared to remain blissfully unaware that she was virtually the only woman in the country for whom this was true. During much of her reign many women quite literally had fewer rights than a dog. Animal cruelty legislation was first mooted during the 1820s, but violence and cruelty towards women was not legally recognized for another thirty years and it was not until the 1870s that legal existence and rights for married women were enshrined in law. Before that time women were simply regarded as their husbands property (although obviously not in Queen Victorias case), whose sole purpose in life was to be loving, patient, self-sacrificing and always understanding of their husbands every whim and desire at all times, regardless of their own feelings or situation. Deemed the Angel in the House by Victorian poet Coventry Patmore, he wrote in 1844 that women should not even think about life after their husbands had died but should make every attempt to die of a broken heart. In 1941 this so enraged the writer Virginia Woolf that she declared killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.

Nevertheless, during the century from 1850 to 1950 an enormous number of changes were made to the lives of women which eventually instigated the feminist movements of the 1970s and 1980s, seeking to establish equality and opportunity in all aspects of womens lives. It should have been a good and exciting time to be a woman but, as usual, history proved to be cyclical and old prejudices die hard. The most positive summary is that of two steps forward, one step back. Progress has been made but at a price, and even today some Victorian attitudes can still be discerned just below the surface. A major step forward in the struggle came in 1918 with the granting of the vote to women aged over 30 followed by universal suffrage ten years later in 1928. The main initiative in the struggle for female emancipation and equality originated, unsurprisingly, in the millscapes of north-west England where hundreds of thousands of women in the nineteenth century suffered the most appalling living and working conditions, endured countless hardships and heartbreaks, struggled with high infant and maternity mortality rates, and prayed for death to release them from their suffering. Their plight was largely ignored by the establishment and by many men but not by their female contemporaries, some of whom were in more fortunate circumstances, and slowly the movement for change began to grow, challenging long-held views, gathering impetus, and culminating into the most tremendous show of solidarity, strength, support, ability and determination which finally enabled Britain to win the Great War. Their reward was female emancipation but that was only the beginning of the story. This book is a tribute to the countless thousands of women from Manchester and its townships, most of whom are anonymous and whose lives are lost in history, to celebrate their stoicism, their efforts and their contributions to sisterhood, helping women to take their place as first-class citizens rather than being relegated to second-class human beings.

Quite how and when the British started to disrespect, dislike and dismiss their womenfolk as second-class citizens is lost in the mists of time. Anglo-Saxon women certainly had greater freedoms in many respects than their later counterparts and there are sweet romantic visions of early medieval troubadours singing love songs to woo the girls of their dreams. In later medieval times, however, women were often regarded simply as pawns to be used in empire-building through advantageous marriages and by the time of Henry VIII no one raised much protest when he had two of his six queens beheaded. The reduction to second-class citizen status for women, as advocated by the patriarchal Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, may well have been encouraged by the Norman invasion of 1066. France is a Catholic country and the Catholic Church gained in ascendancy over the indigenous Celtic Church after the Conquest. The Catholic Church is strongly patriarchal and attributes all original sin to Eve; i.e. woman. Although Henry VIII replaced Catholicism with the Church of England in 1534, many of the old religious views remained and, even today, the Church of England does not easily embrace women as equal citizens.

Britain is also one of the most class-conscious countries in the world. The Industrial Revolution, which really began to gather steam in the late eighteenth century, was a major catalyst for the whole question of class. Before this date class tended to be based on hereditary characteristics such as family, rank, estate ownership, hierarchy within religious orders, etc. One of the constant beliefs of the upper classes was that old families must be preserved at all costs. All families are old in the sense that they must have had ancestors back into pre-history or they would not exist today. People dont just appear from nowhere. What was really meant was that old families could trace their lineage back several generations; a few as far back as the Conquest which was when titles and large estates were handed out as rewards to those who had fought well for the winning side. It was generally accepted that a lot of class was due to bloodline, with the royal family and those at the top of the upper-class tree often being referred to as blue-blooded. The reality is rather more prosaic. There are four main blood groups: A, B, AB and O, each with rhesus positive and rhesus negative divisions. No single blood group is unique to any one class of people and all human blood is red. Ironically, some living creatures such as spiders, crabs, squid, octopus and a number of invertebrates do actually have blue blood due to using haemocyanin rather than haemoglobin to circulate their oxygen supply. Although science had not yet fully explained these basic facts in the late eighteenth century, changes had begun to occur and, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, wealth and income became the major criteria for class rather than breeding, i.e. a long-recorded noble lineage, although those who bought in were sometimes sneeringly referred to as the nouveau riche. There are precedents far back in pre-history for a social hierarchy based on personal wealth. Archaeology has shown that farming settlements in the New Stone Age were collections of evenly-sized evenly-placed dwellings, and bartering, not money, was the form of exchange for goods. Some folk were better hunters or better farmers; others could make better baskets or weapons or pottery. Meat and wheat could be exchanged for spears, baskets and bowls. The discovery of precious metals turned the social order upside-down as folk who owned anything made from these coveted metals were looked up to, admired and somehow considered to be better persons.