This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother Myra, whose spirit, humour and love of history had a very positive effect on my life.

It has been well and wittily said, The body and the mind are like a jerkin and a jerkins lining rumple the one, and you rumple the other. I may add, ill-use one and you ill-use the other; injure the one and you injure the other.

James Loftus Marsden, The Action of the Mind on the Body, 1859.

I would like to express my appreciation to the following:

At Robert Hale my patient editor Nikki Edwards.

The staff at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. It was a special privilege to read the Reverend John Rashdalls diaries in the ancient Duke Humphrey Room.

The Worcestershire Records Office

The Worcestershire History Centre

Malvern Library

Hastings Library

The staff at Montmartre Cemetery, Paris

Individuals Robert Dudley, Timothy Stunt, Cora Weaver, Randal Keynes, Carlton Tarr, David Force, Derek Wain, Brian Iles, Errol Fuller, plus the many other people who took the time to answer my countless emails and letters. A special thanks to family and friends in Australia and the UK for their support and encouragement. Above all, I would like to thank my partner, Rob. This book could never have been written without his love and faith, not to mention his skills as photographer, chauffeur, proofreader, computer technician, coffee maker etc. etc.

W ithin the churchyard of the beautiful old Priory Church at Great Malvern in Worcestershire are the graves of two young girls. Once playmates, they died less than three years apart. Flowers have been planted around the smaller grave and visitors often leave tributes below its curved headstone. There is a loving dedication:

ANNE ELIZABETH DARWIN

BORN MARCH 2 1841

DIED APRIL 23 1851

A Dear and Good Child.

Several metres away is a flat, weathered stone covering the remains of Lucy Marsden. The iron railings once enclosing the plot were removed to provide scrap metal during the Second World War. Few people seek out the grave, or pause to decipher its inscription:

LUCY HARRIET MARSDEN

DIED SEPT 1853 AGED 14

It could be said that Lucy died because, unlike Annie Darwin, she was not viewed as dear and good.

Neither of the girls had been born at Great Malvern. It was the towns reputation as a health spa that attracted the attention of their respective fathers. The famous naturalist Charles Darwin first visited Malvern as a water-cure patient in 1849. Doctor James Loftus Marsden arrived in 1846, an ambitious young physician specializing in the unorthodox therapies of hydropathy and homeopathy.

Inside the Priory Church is an honour board of past vicars. The Reverend John Rashdall is listed as serving from 1850 until 1856. It was John Rashdall who delivered the sermon at Annie Darwins funeral. He also sat by the bedside of the dying Lucy Marsden, but although he attended her burial service he was too distraught to take his place in the pulpit.

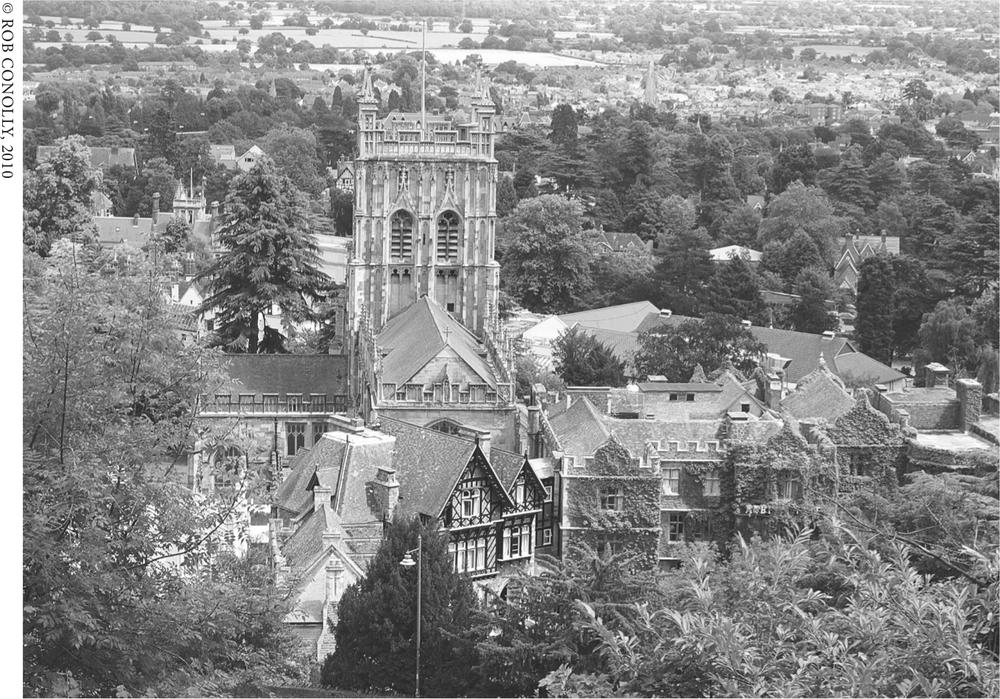

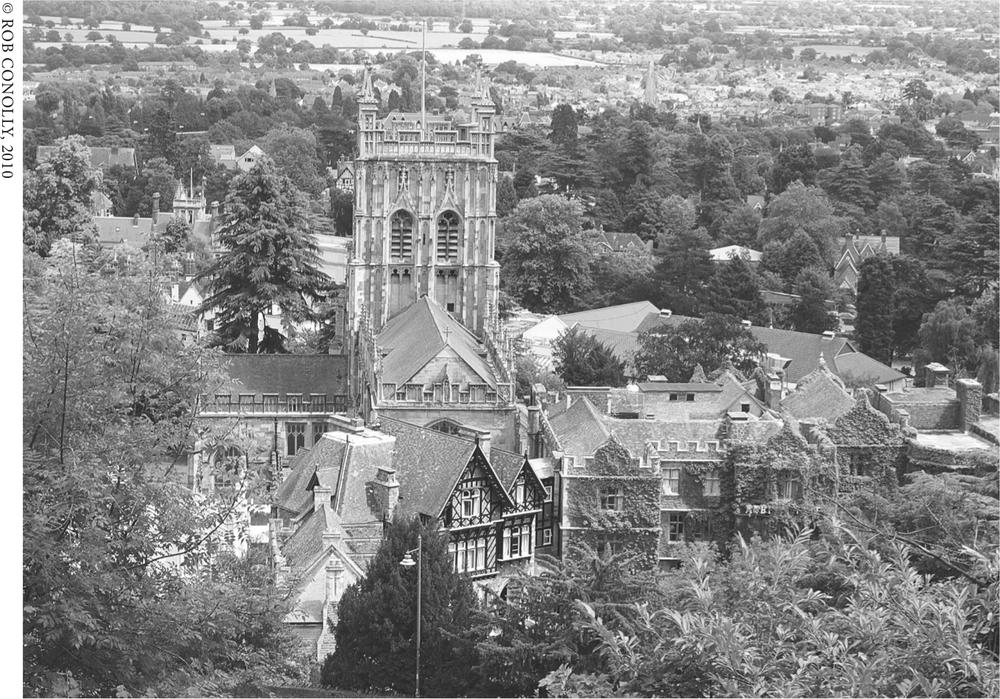

T he village of Great Malvern grew up on the eastern slopes of Worcestershires Malvern Hills, following the establishment of a Benedictine monastery in 1085. In the wake of Henry VIIIs dissolution of the monasteries, the Priory Church was purchased by the local community. Dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, it still serves as the towns parish church. St Marys medieval stained glass windows are acknowledged as some of the largest and finest in England. Other treasures include a collection of 1,200 medieval tiles, handmade by the monks, and elaborately carved misericords or mercy seats, dating from the fifteenth century.

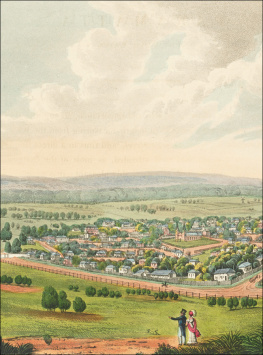

Overlooking St Marys Priory Church and the town of Great Malvern

Malvern quickly became known for its healing wells, fed by crystal-clear springs filtering through the surrounding granite and limestone hills. In 1756 Dr John Wall famously proclaimed that Malvern water was so pure it contained just nothing at all! By the turn of the century the spa centre had become fashionable, and more than a little snobbish. When the novelist Catherine Hutton visited in 1802 she was almost turned away from the Well House Hotel until making it clear she was a gentlewoman:

I entered the Well House alone, and without attendants, having walked up the hill. The master of the house seemed doubtful whether he should let me in he would Enquire of the chambermaid whether there was a vacant bedroom. I have a chaise, a horse, and a servant with me, I said. This settled the point, and I was conducted to the vacant bedroom.

During the early 1820s a pump and commercial baths were established, a development followed several years later by the social coup of royal patronage. In the summer of 1830 the Worcester Journal proudly announced that the Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria, 12- year-old heir presumptive to the British throne, were to visit Malvern for six weeks: The presence of the Duchess and her interesting daughter will no doubt attract numerous visitors. However, it was not until the introduction of Vincent Priessnitzs famous water-cure in 1842 that Malvern really began to capitalize on its natural gifts.

Priessnitz (17991851) was a peasant farmer from the village of Graefenberg in Austrian Silesia, now part of the Czech Republic. It was said that after watching a fawn heal itself by bathing in a mountain spring he wrapped wet bandages around his own ribs, which had been fractured in a cart accident. Several months later Priessnitz declared himself cured and began treating neighbours and their livestock. Word spread and in 1822 he opened a small clinic. By 1839 it had evolved into a sanatorium treating some 1,500 patients per year. The regime was rigorous to say the least. Patients were housed in rough, army-style barracks and awakened by attendants at first light to be swaddled in wet sheets. This was followed by therapeutic baths, douches and cold compresses plus the drinking of vast quantities of spring water. Long walks, a plain diet and strict abstention from alcohol and tobacco formed an integral part of the cure.

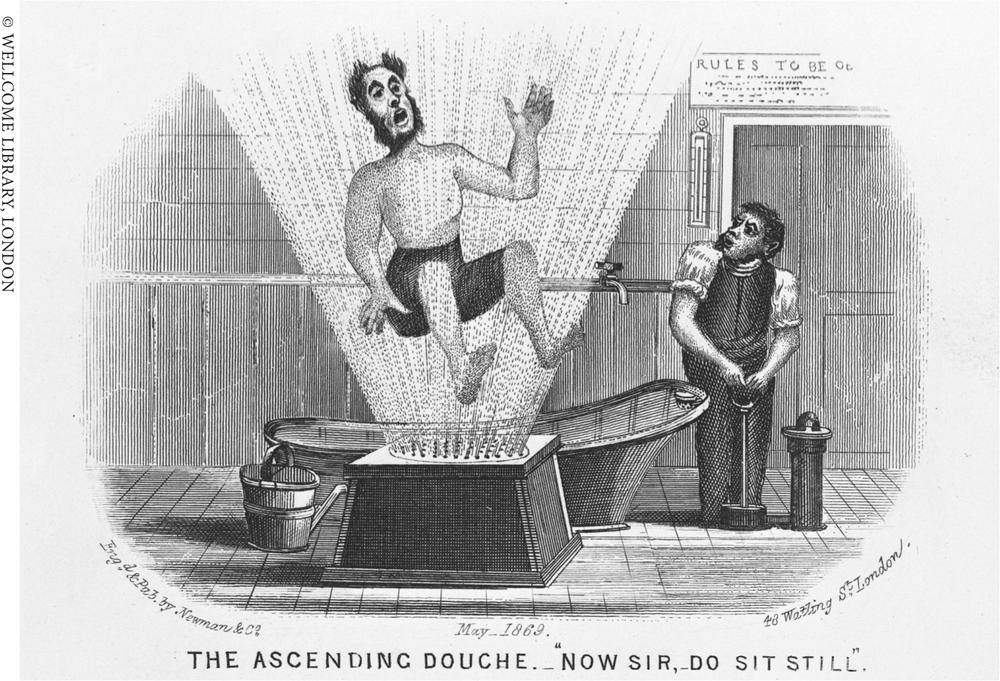

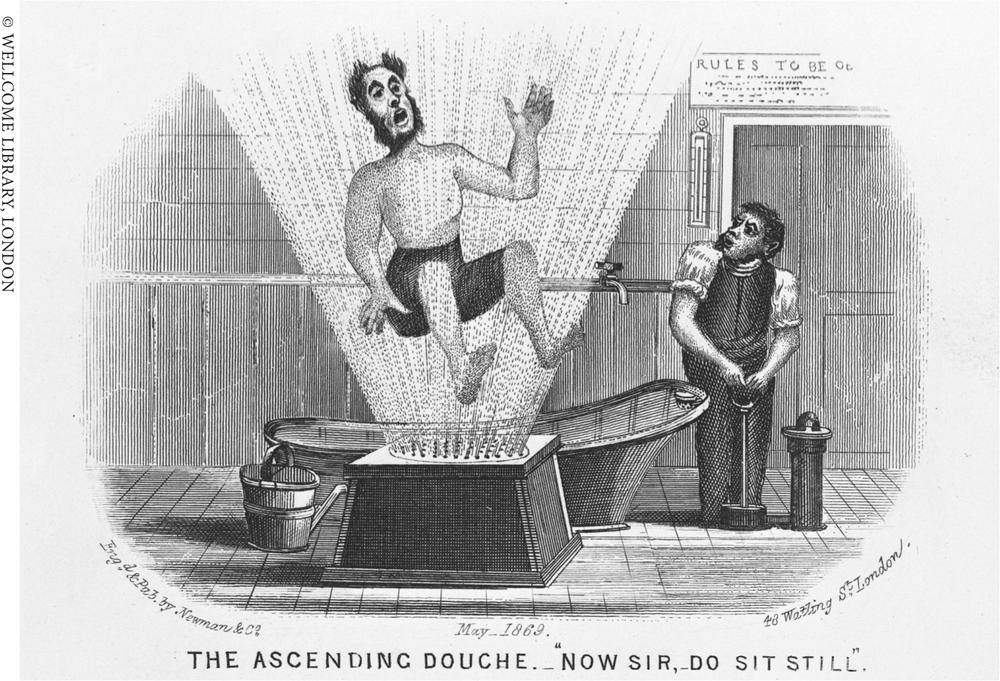

The unorthodox therapies involved in the water-cure provided an easy target for cartoonists

In 1842 Englishman R.T. Claridge wrote a glowing account of the treatment at Graefenberg in Hydropathy or the cold-water cure as practised by Vincent Priessnitz. However, not everyone was impressed. Shortly afterwards a humorous review appeared in an English magazine. The writer joked that damp sheets were already well known to the chambermaids of Englands inns, and that while the water used in the cure may have been ice cold, Priessnitz had made himself warm to the extent that he was already worth 50,000. Dismissing hydropathy as pure quackery, the article continued: