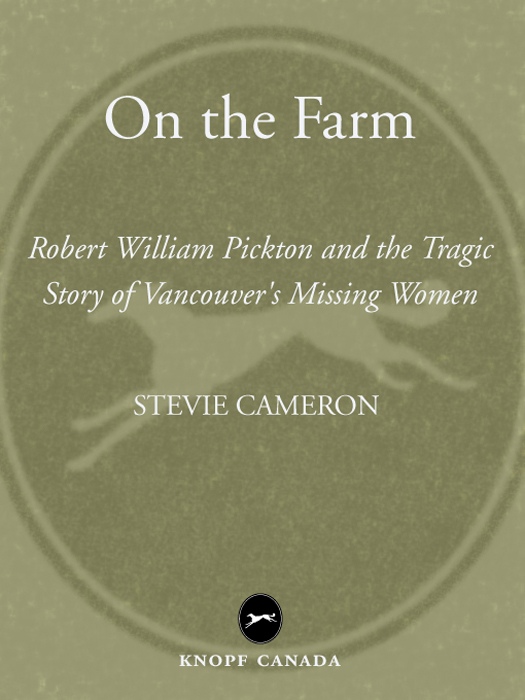

Readers will find many conversations in this account of the Pickton murder case. Some of these come from transcripts of police interviews done during the investigation and made available to me by participants in these conversations. Other conversations, such as the one between a woman I am calling Sandra Gail Ringwald, a woman whose real name is still under a publication ban, and Robert Pickton in his trailer in 1997, were recounted in court; in this case, by Ms. Ringwald. (Her case is strange in Canadian law: Normally, all publication bans disappear when the Supreme Court upholds the verdict as they did in this case, but in an extraordinary ruling the trial Judge, James Williams, ordered the continuation of the ban on her real name and the matter is now before the courts.) To protect her identity, I am referring to the father of her children as Paul Campbell. Most of the conversations Pickton had with RCMP Constable Dana Lillies were recorded and played in court proceedings; so were the lengthy interviews with Pickton done by an undercover police officer in his cell, by Bill Fordy and by Don Adam. And some conversations were those Pickton had with women he picked up, women like Katrina Murphy, who shared them with me.

PROLOGUE

JANE DOE

At first he thought it was an old brown bowl, just perched there on a bed of rocks, surrounded by reeds and bushes. But when he walked over to have a closer look, he could see it was a human skullcut in half, yes, yet still recognizable as human. And Bill Wilsons first thought as he walked back to the road was that he should probably call the police. But this was a human skull and he had a serious police record. Maybe the first thing theyd do is start looking at him for it.

On this February 23, 1995, Wilson, who made his living as a woodcarver and handyman, had been on his way to get some water from a narrow slough that ran along the south side of the Lougheed Highway, close to the mouth of the Stave River, about forty kilometres east of Vancouver. He wanted to clean off his car, which was parked on the north side of the highway in a paved public lay-by where he kept a little roadside stand displaying his wooden bird feeders, birdhouses and whirligigs to drivers passing by. Wilson had just run across the road with a water bottle and clambered down the six-foot slope to the rocky edge of the slough when he spotted the skull about forty or fifty feet away. He walked over and, using the bottle, flipped it over; that was when he realized what he was looking at. He didnt do anything about his find immediately, Wilson told the police later; he had a doctors appointment and some shopping to do that afternoon. But if hed seen a police car coming along, he declared, he would have flagged it down. And as for why he didnt call them that night, well, he had bingo to go to, and anyway he didnt have a phone at home. Given his recordtwo convictions and jail time for indecent assault and sexual assaulthe didnt want to get involved.

But twenty-four hours later on Friday afternoon, Wilson decided hed better report what he had found. Just before five oclock in the afternoon on February 24, 1995, he drove east into Mission, the nearest town with a police station. As soon as he saw a police car, he stopped it.

The police officer called the Mission RCMP station on Oliver Street, and almost right away the control officer called Constable Chris Annely, on duty in his cruiser, and asked him to meet Wilson, who would be waiting for him at the Stave River lay-by. Wilson, the dispatcher explained, would point out some human remains hed found the day before.

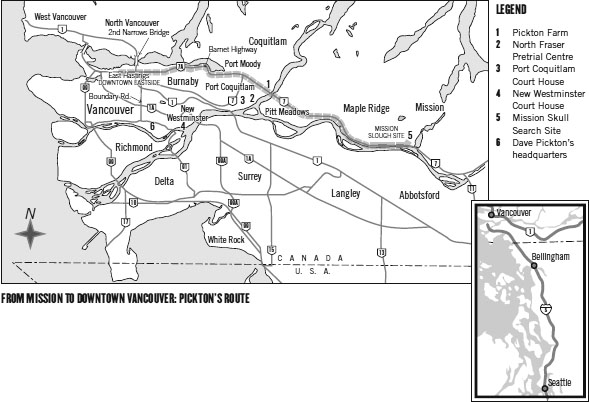

Annely knew the location well. The Lougheed Highway, the old Number 7, once the main road between Vancouver and Hope, stitches together most of the small working-class towns along the north banks of the Fraser River. Running east from Vancouver, the Lougheed stretches through Burnaby, Coquitlam and Port Coquitlamthe Tri-Cities area, as its calledto Maple Ridge, Mission and Agassiz before it reaches Hope. Most drivers choose the much faster Trans-Canada, the superhighway that runs along the south side of the Fraser, but the Lougheed is what you take if youre a local.

And this small stretch of the Lougheed, where Bill Wilson was waiting for Chris Annely, is one of the prettiest parts of the highway. Now, in early spring, leaves were just beginning to come out on the trees and the riverbanks were greening up.

Silvermere Lake is a popular resort area near the Stave River where many people have built new ranch-style houses back from the shoreline; their lawns are green and well-tended. A small Indian reserve is wedged into the few acres between the lake and the Stave River; across the highway is the Fraser River. In fact, the highway where Wilson was waiting is really just a bridge, not more than five hundred feet long and banked on each side by deep sloughs crammed with alders and dense brush. The south side beside the Fraser, crowded here with log booms, is where the main VIA Rail track runs on its way east to Toronto, perhaps a couple of hundred feet from the road. Local fishermen, most from the Stave River band, often make their way down the bank on this side to cast their lines into the river for salmon.

When Annely pulled his cruiser into the lay-by, he spotted Wilson waiting for him. Wilson led the policeman down the steep bank to an area about halfway between the highway and the train track. Three large rocks, left over from the highway construction, bumped up through the reeds and bracken. Water still pooled in the low spots, but Annely could see the small, dark object on the ground in front of the rocks. No question, he thought. Wilsons right. Its a human skull.

Annely hurried back to his car and grabbed his radio. We need a camera here right now, he told Corporal Brad Zalys, the officer in charge at the detachment. The men didnt have long to wait; Zalys was there by 5:35 p.m., when there was still enough light left to get a few decent pictures of the skull on the ground. In fact, it was just half a skullsplit in half vertically, cleanly, from the crown down through the back of the head and the jawbone in front. A small scrap of the first vertebra was attached to the neck, but there was no sign of the other half of the head. What they were almost certain of, however, was that this skull had not been there a long time; scraps of white flesh clung to the areas around the eye socket, and the nose was still attached.