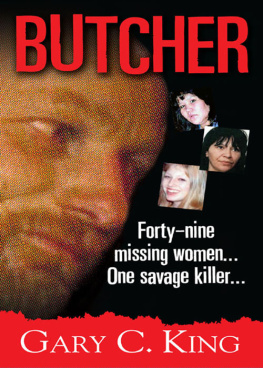

PICKTON INDEX

Number of women on official police list of missing women since 1978: 65

Number of women who have turned up alive: 4

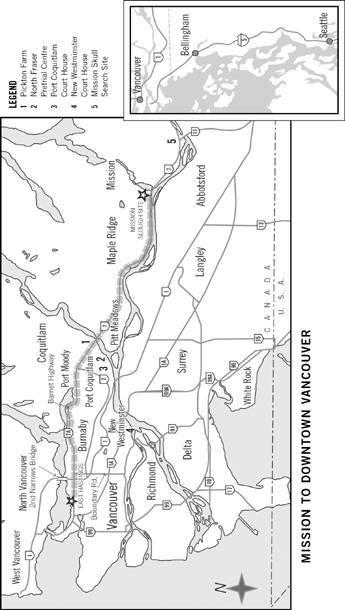

Number of women Pickton is charged with killing: 26

Age range of the women Pickton is charged with killing: 20 to 46

Number of tips received by the Missing Women Task Force: 12,700

Number of pages that would be in the investigations database if they printed it out: 2 million

Number of exhibits seized by police: 600,000

Number of DNA samples processed by the RCMP crime labs: 200,000

Number of swabs used to capture DNA: 400,000

Number of cubic yards of soil sifted by investigators: 383,000

Number of RCMP crime labs used: 6in Vancouver, Edmonton, Regina, Winnipeg, Ottawa and Halifax

Number of media involved: about 378 accredited for trial

Number of journalists showing up every day of the trial: between 2 and 6

Number of prosecutors working for the Crown in court: 7

Number of defence lawyers working for Pickton in court: 11

Cost of investigation to date: about $100 million

Number of judges involved in the case so far: 4

Number of Crown witnesses: about 240

Number of vehicles to bring Pickton to court: 3

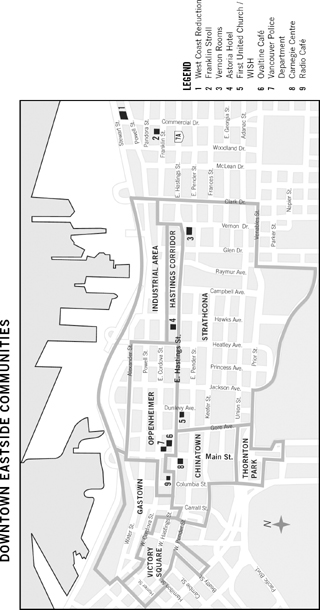

Population of the Downtown Eastside: about 17,000

Number of single-room occupancy rooms in the Downtown Eastside: about 5,000

Monthly shelter allowance for people on welfare: $375

Monthly rent for SRO room in the Downtown Eastside: $375

Monthly living allowance for people on welfare: $185

Number of addicts in the Downtown Eastside: between 4,000 and 5,000

Rate of injection drug-users in the Downtown Eastside with hepatitis C: 9 out of 10

Rate of injection drug-users in the Downtown Eastside who are HIV positive: 3 out of 10

Average amount spent per day on drugs (mostly cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin and crystal meth): $200$400

Number of detox beds for men in the Downtown Eastside: 23

Number of detox beds for women in the Downtown Eastside: 6

FOREWORD

I remember the sense of relief I felt when I learned in the late spring of 2002 that Stevie Cameron was starting research for a book about the case of Vancouvers missing women. I was in the middle of a movewashing floors, packing boxes and listening to CBC Radioand heard Stevie being interviewed. Id read two of her books, Ottawa Inside Out and her mammoth bestseller On the Take, and knew her to be a tenacious reporter with impressive investigative skills. It would take someone with her ability to do justice to the story, which will ultimately conclude, we all hope, with justice for the missing women and justicein the sense of actionfor women who, as a result of their addictions and other problems, remain vulnerable to twisted men.

The story of Vancouvers missing women is a big one. It spans several decades and multiple police jurisdictions and involves over sixty women. I knew twenty of the women who went missing from the streets of the Downtown Eastside. I met them while I worked at WISH, a drop-in centre for sex trade workers, housed in the back of the First United Church on East Hastings Street. WISH is an acronym for Womens Information Safe House. Ina Roelants named the centre when she helped start it up in 1982. She encouraged women to phone their families on a regular basis and thought some might hesitate to call home if the place they were calling from could be identified as a drop-in centre for sex trade workers. A true champion of marginalized women, Ina operated WISH from five p.m. to twelve a.m., five nights a week, for five years, taking home only $100 a month for her efforts. Ina died from bone cancer in March 2005, leaving behind a legacy of support for street-entrenched women that remains unparalleled on the Downtown Eastside.

Ive listened to many stories about the women who have gone missing. My earliest recollection dates back to 1998, when Sereena Abotsway told me the police had mistaken her for Angela Jardine. Angela Jardine and Sereena Abotsway were regulars at WISH. According to Sereena, Angelas parents had been trying to report her missing for months, only to be told their daughter was alive and well and working as a prostitute in the Downtown Eastside. Eventually, it was established that the Angela spottings were a case of mistaken identity. Both Angela and Sereena were white women who could have passed for Native; both had brown hair, were in their twenties and were of similar height and weight. Sereena wasnt fazed. She knew many of the women who went missing from this neighbourhood. In 2001, Sereena Abotsway herself was reported missing; in 2002, both Angelas and Sereenas DNA was found on the Pickton farm. Robert Pickton was later charged with their murders.

The women at WISH talked about the events that led them onto the streets of Vancouvers drug ghetto. Many told horrifying tales of child abuseparents or caregivers who exploited them sexually, physically and emotionally when they were young. Some battled with mental health issues that entrenched them in a downward spiral of addiction and poverty. Others were lured into addiction and the sex trade by boyfriends who introduced them to drugs.

When I began working at the drop-in centre, I knew little about addiction, street life or the sex trade. My previous job had been in the communications field, where I spent a great deal of time office-bound, sitting in front of a computer. At WISH, I worked with a group of women in continual flux. Some women were regulars and came to the centre every night; some would come only once or twice a week. Others were more irregular in their attendance and would come a few days in a row, then skip a week or two. I approached all the new women who came into the centre to welcome them and give them a quick rundown on dinner hours and accessing the showers in the womens bathroom.

Some nights were quiet, others were more animated. Women would sometimes charge through the doors, fleeing from men who were chasing them: drug dealers they owed money to, or violent men who prey upon sex trade workers. Surprisingly, the men pursuing them would stop when they reached the doors of First United. I worked without security, and there wasnt much in place to protect myself or the clients, so we were fortunate that there was respect at street level for the institution that housed the drop-in centre.

Clients sometimes asked me to help them report women who had gone missing. In most cases, the clients had previously approached the police but were upset because there had been no follow-up. One afternoon, early in 2000, I was alone in the church foyer, preparing for the usual six oclock dinner rush. A client named Ashwan banged on the locked church doors. I let her in. She was crying and out of breath. Tiffany didnt come home last night. Somethings wrong. Ashwan and Tiffany Drew were best friends and shared a room at the Hazelton Hotel, less than a block from the centre. When they came into WISH, the friends would eat dinner, experiment with makeup and do their hair. I asked Ashwan if it was possible that Tiffany had spent the night at someones house. Perhaps she hadnt made it home yet. No, Ashwan explained. Ashwan and Tiffany knew that women were going missing from the Downtown Eastside, and they had agreed to check in regularly and let each other know they were safe. Many women at WISH were using the buddy system for the same reason: women were going missing from the neighbourhood at an alarming rate.