ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Beautiful Eyes would not have been possible without Sarah. I will always be grateful for the honesty of her response to this book, and her gracious acceptance of the ways in which it has failed to capture her depth, courage, wisdom, and humor.

This book was, at times, painful to write. Sally has been steadfastly supportive. Without her encouragement I doubt that I could have completed it. Sally also helped me remember and understand what really happened in the early years of our marriage and family. She was honest when she thought I wasnt remembering it correctly, or rendering it accurately. John and Sam have both read it, and offered invaluable insights.

So many other people helped me as I wrote this book; it is inevitable that I will fail to mention someone, and I wince at that thought. But here goes. The people at the London Metropolitan Archives, and The John Langdon Down Centre were very generous with their time and expertise, as were the people at the Hartheim Memorial.

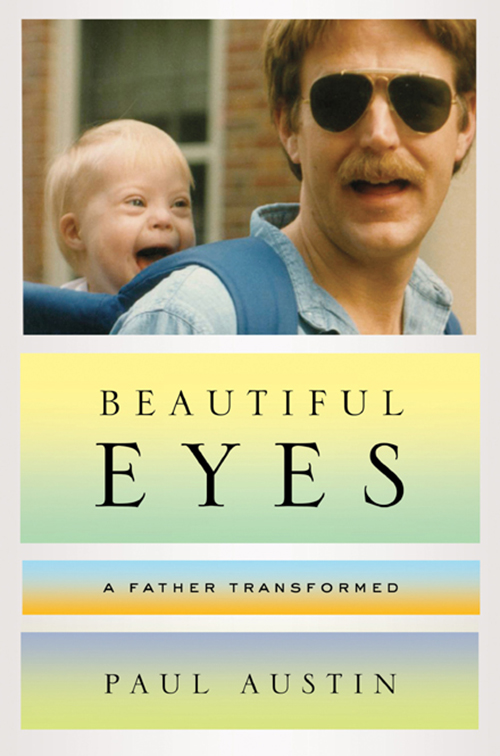

Judy Goldman, Peggy Payne, Nick Flynn, and Mary Akers all offered invaluable help with the writing itself. So did Sally. Michelle Tessler is the best agent I could hope for. Allegra Hustons herculean efforts improved the formatting, style, and accuracy of the book. Rebecca Schultz and Angie Shih helped shepherd the book along at Norton, and the design team has created a beautiful book. I love the cover.

I dont know how Jill Bialosky does what she does, but she helped me see what the book could be. Im a better writer for it, and this books a better book.

ALSO BY PAUL AUSTIN

Something for the Pain:

Compassion and Burnout in the ER

Chapter One

We had thought we were ready. Sally had been a nurse in labor and delivery, and I was a third-year medical student. This was our first pregnancy, and it had gone well. Neither of us smoked. Sally hadnt drunk any alcohol since we started trying to get pregnant.

She had a dancers body, and both of us marveled as it changed. From behind, she was still skinny Sally, with her broad shoulders and narrow hips, but when she turned sideways, her belly would swing out into view, massive and majestic, like a full moon filling a horizon.

We were both familiar with the matter-of-fact intimacy of childbirth: the bodily fluids and animal smells, the laboring womans face red, her eyes squinched tight, legs spread wide, the baby slithering out fast like an otter, so sleek, the legs trailing, umbilical cord corkscrewing, glistening, it all happening so fast after all those hours of labor.

We had both scrubbed in on C-sections as well, and knew the measured cadence of the surgeons work. Every move choreographed, practiced, and precise. It begins slowly but the pace picks up as they cut through the layers of the belly, down to the baby, and pull it up, out into the light and air.

We had both read What to Expect When Youre Expecting.

A month earlier, Sally and I were in our apartment at married student housing, lying on our backs, touching hip and shoulder. There are three of us in this bed, Sally whispered, slowly skimming her hand across her bare belly. She turned toward me, and brushed the hair from her face. Yow, she said. Somebodys stretching. She took my hand and placed it against her belly. Feel that? Must be a foot.

The skin of her abdomen was smooth and warm, and stretched tight. The uterus, firm beneath her skin, felt muscular. A solid little lump pressed up against my palm. For weeks, Sally had been feeling the baby moveshe would grab my hand and put it against her belly so I could feel it too. But I was always a fraction of a second too late.

Years before, lying on our backs beneath a late summer sky, long after midnightSallys ideawe were watching for shooting stars. Theres one, she said, pointing off to our left. I missed it. I gazed again, straight up. Another one, she said. And another.

Finally I saw one, a silent white streak, impossibly thin against the black and star-crowded sky.

I felt the babys movement just a second too late. Too slow. And a fear that perhaps I was missing it because I was trying too hard. Wanting it too much.

Whats it feel like? I asked.

Sally looked down and placed her hands on her belly. When I first felt it, it was like a butterfly inside, opening and closing its wings. Now it feels stretchy.

The smells of our bedso familiar and subtle that I hardly noticed themseemed richer. And the way I nuzzled Sallys neck was different. Gratitude was involved, and mystery. And at the center of the mystery was the way her body was changing.

We were playful as we accommodated the expanding heft of her belly. Our bodies moved with a rhythm that needed no instruction: like breathing or swallowing, every cell moved exactly as it should. And each cell was packed with a wispy double helix of DNA, those angstrom-thin strands that coded for our humanity and tethered us to our ancestral past.

Wed been married three years when Sally got pregnant. We hadnt done amniocentesis because, based on the results of the and others are not.

The term normal, when used to distinguish persons without disabilities from those with disabilities, is at its core offensive. It is, however, a word I have used, and to pretend otherwise would be untrue. Later in this book Ill talk about the way this nomenclature distorts the way we think about one another.

Chapter Two

Dr. Gage, the obstetrician, came to talk with us again in the post-op bay.

Have you chosen a name? His tone was pleasant, matter-of-fact.

Wed been planning to name the baby Sarah if it was a girl. But I didnt know if we wanted to still use that name. Wed been expecting a different child. A normal one. I looked at Sally.

Sarah, she said. Well call her Sarah. Sallys voice was raspy.

What a pretty name, Dr. Gage said, and what a pretty baby.

Sally and I stared at him.

Sarah will be more like other children, he said, than unlike them. He paused, and then said, The pediatricians will want a chromosomal analysis, but thats just a formality. He looked to Sally, and then me. She has it.

Sallys lips tightened. Her eyes squinted against the glare of the light above.

Well get an echo of Sarahs heart. She may or may not need surgery. He paused again.

Maybe the hole in her heart would be so big she wouldnt survive. She could die on the OR table. We could put her in a small white coffin, deal with the loss, and then move on. Try again in a couple of years. Have a normal family. I felt my face flush.

Sometimes a parent feels that it may be best if a child dies painlessly and quickly. He looked from me to Sally, and back to me. Others dont have that feeling. Whatever youre feeling, you should know that lots of people have felt the same way.

I felt like crying. I took a deep breath and felt my lungs expand. I let it out, slowly.

For the first few months, Dr. Gage said, youll be caught up in all the routine baby stuff: breastfeeding, diapers, car seats, and baby buggies. But in about six months youll get the hang of it, and then all of the other issues will bubble up. A new baby puts a huge stress on a marriage. I tell all couples to think about seeing a counselor at about six months. Just to air things out. For you guys, I think it would be especially important.

I nodded along with Sally, but I was faking it. Six months? I dont know how well make it to tomorrow morning.

One last thing, Dr. Gage said. This isnt your fault. When something like this happens, we always look for a reasonits human nature to want to know what couldve caused it, or some way it couldve been avoided. But in this case its nothing you ate, drank, or smoked. Nothing you did or didnt do. It just happened.

Next page