XAVIERA HOLLANDER

CHILD NO MORE

A M E M O I R

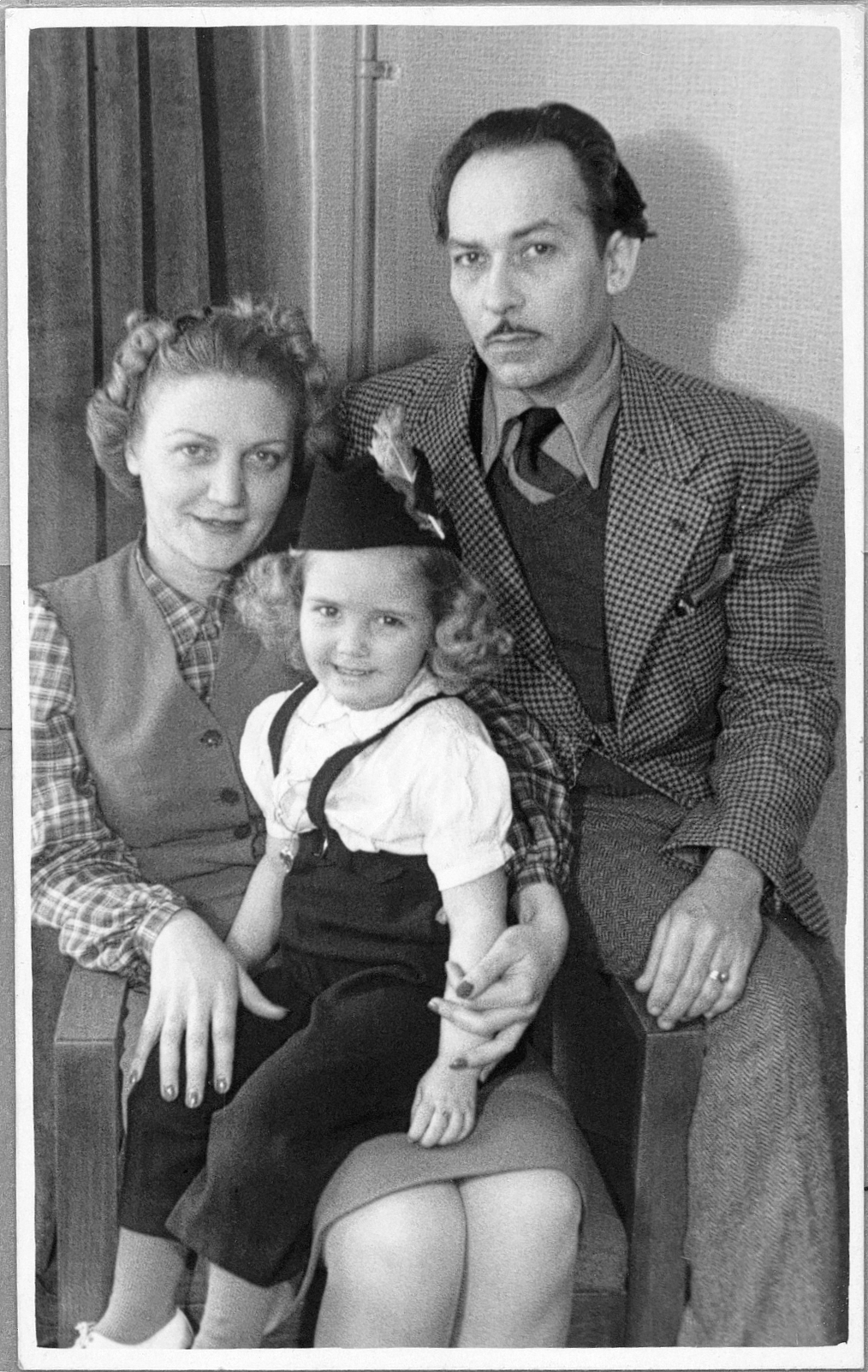

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO

THE MEMORY OF GERMAINE AND MICK,

THE TWO COURAGEOUS PEOPLE WHO WERE

MY LOVING PARENTS.

AND YET

IT IS ALSO AN ODE TO MY MOTHER.

When you are a mother, you are never really alone

in your thoughts...

A mother always has to think twice, once for herself

and once for her child.

SOPHIA LOREN

Contents

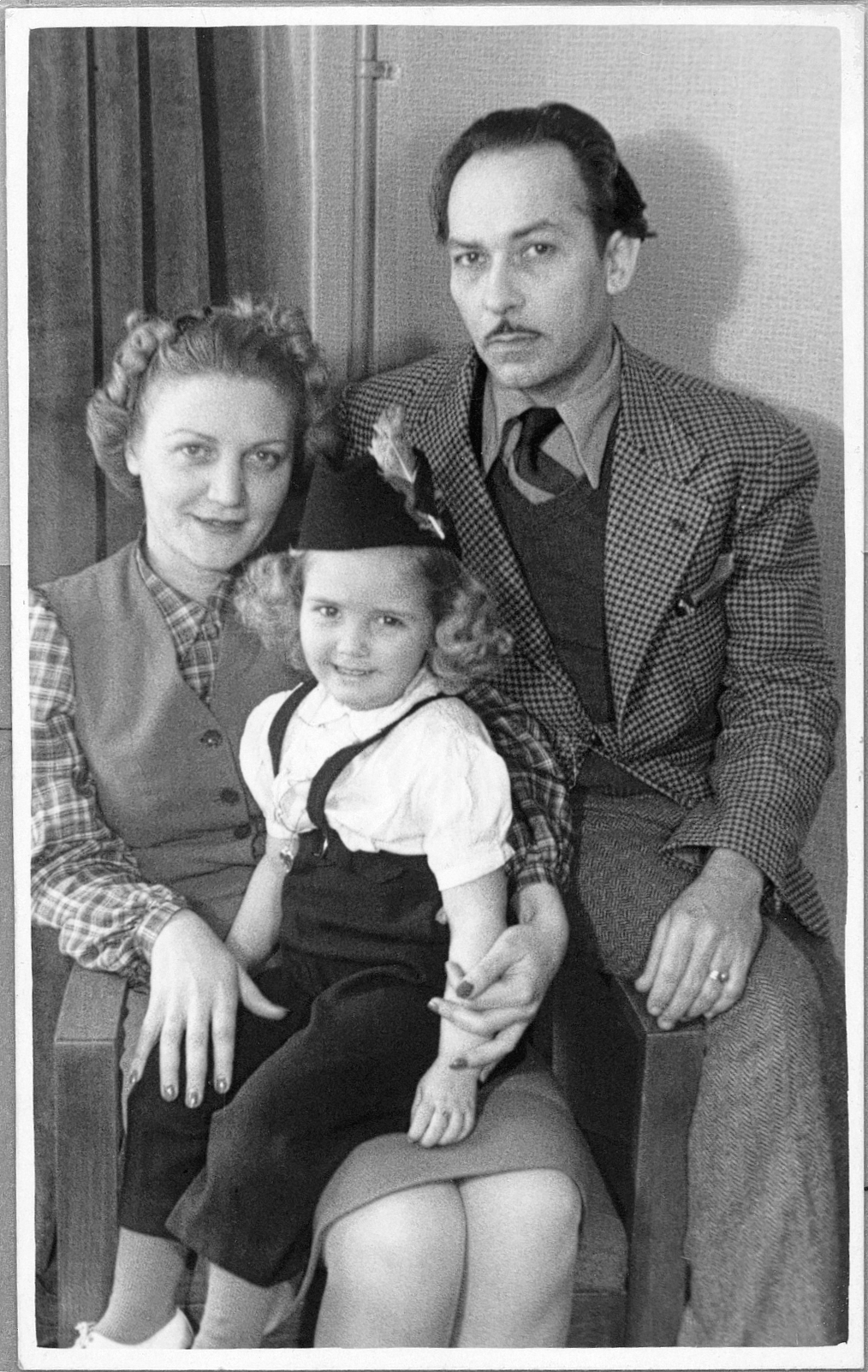

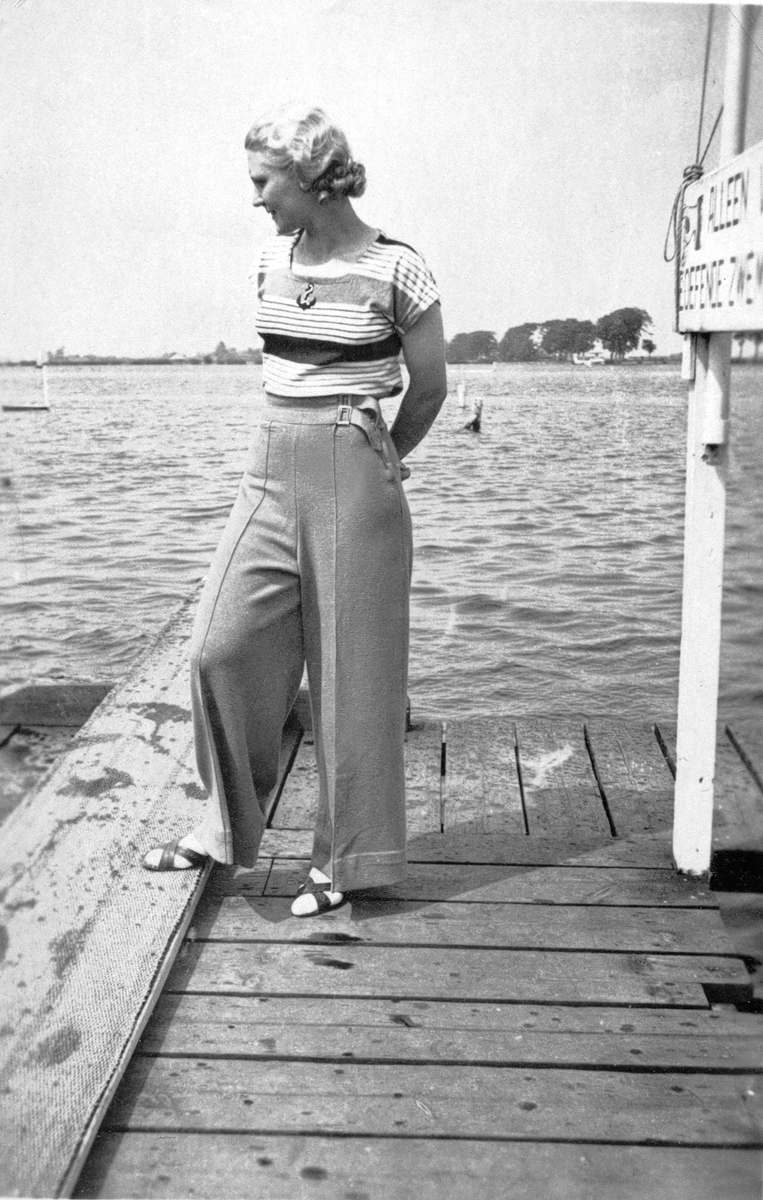

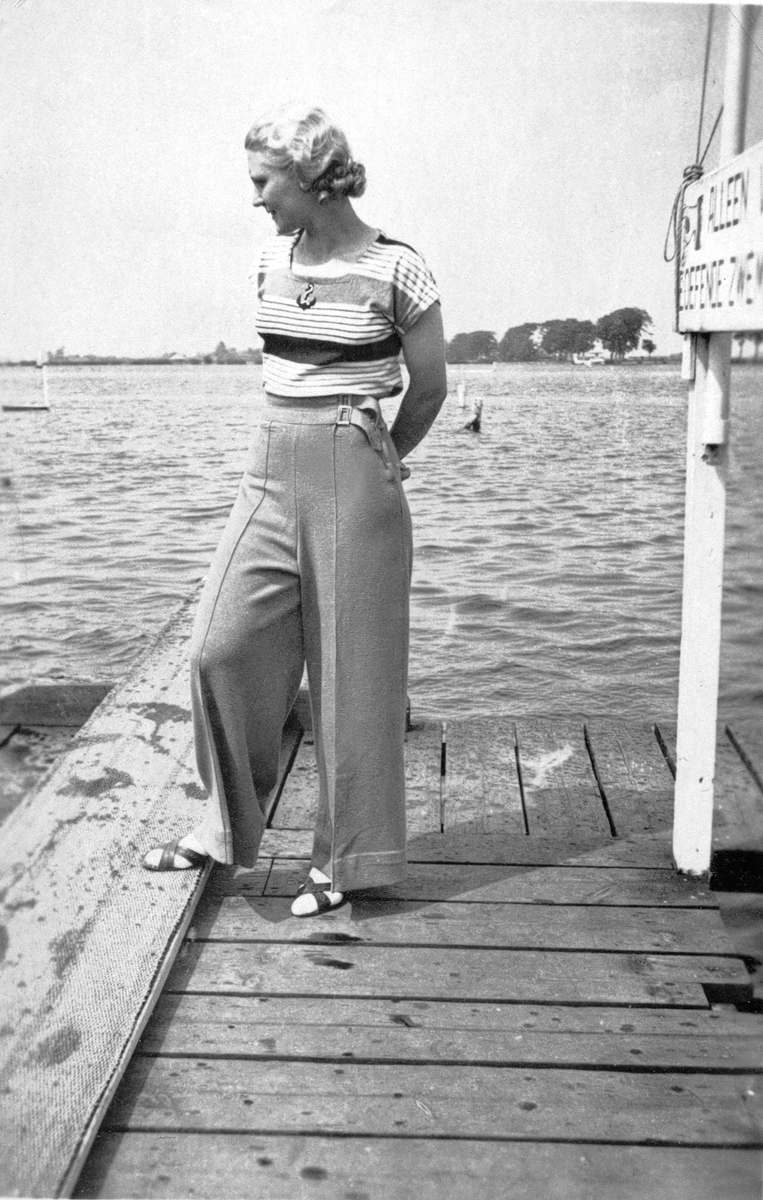

Germaine, 1938

DAY ONE. Tuesday afternoon, July 6, 1999

I remember the moment I received the phone call from the head nurse. It was seven oclock in the evening.

Your mother is in critical condition. Youd better come quickly. I felt numb all over, and my legs seemed turned to lead. When I tried to move, it was as if some force were holding me back. Even to step into my car and turn the ignition key was an effort. I found that my arms were covered with goose bumps and I was icy cold, although the sun was beating down and it was hot as a furnace. I rammed my foot hard down, breaking every speed limit, but it seemed as if some other person had taken over the steering wheel. This was the spookiest thing I had ever experienced, but more was to come.

I had the impression that my father, who had died long before, was beside me, whispering into my ear for me to control my panic.

Slow down. You want to help Momma? Then get to the hospital alive.

I sensed his presence, assuring me that this sort of experience can happen when two people are really close. It was as though I were enveloped by a kind of protective cape, yet at the same time it seemed to be the cape of death. My throat was dry. I was choking. And at that moment my only burning desire was that I should die in my mothers place.

I dont remember actually arriving at the hospital and running into the elevator, but suddenly I was with her, alone in a room, and I understood that this was what the nurses referred to as the death chamber. The final chapter was being written in the book of her life, yet she was still conscious, though pale and tired, a blue-and-white-striped washcloth drenched in icy water on her forehead. She was surrounded by a team of doctors.

A young blond doctor who seemed to be in charge bent over her and bellowed:

Mrs. de Vries? Mrs. de Vries, can you hear me?

He could have been heard a couple of wards away. She turned her head away. Mrs. de Vries, your daughter is here. Can you please answer a few questions?

She nodded feebly.

Are you sad, Mrs. de Vries?

She shrugged her frail shoulders and said nothing.

Mrs. de Vries, do you want to die? he shouted.

I begged him to stop yelling; after all, she was not actually deaf. In a soft, clear voice, she replied, Yes, I want to die. The sooner the better.

I looked at the doctor and pleaded, Please, now that you have heard that she does not want to live longer, can you do some thing about it?

The doctor straightened his back and looked hard into my eyes.

No, madam. We are not allowed to practice euthanasia, not evenm if she had signed all the consent forms. His voice was harsh and grating. St. Lucas is a Catholic hospital; we are not permitted to help patients end their lives prematurely. The most we can do is to stop all life support: no more food, no more medications except painkillers, and no more liquids. I promise we wont even administer a liquid drip. So she will dry out spontaneously; she will be completely dehydrated within two to three days.

My mother understood every word and looked horrified.

We stopped her intestinal bleeding a few days ago. In fact, your mother is not ill at the moment. She is quite anemic from losing so much blood, but if she had any willpower she could actually go home and get better there. She just has not got the will to go on living. He shouted in her ear. Isnt that right, Mrs. de Vries? She gave him a mean look.

A nurse interrupted. I am sorry, doctor, but look at the patients condition. Her weight is down to forty-five kilos. Surely you wouldnt want to send her home in that state, would you?

I nodded and pleaded with him. Please, be kind to her. And what ever you do, dont send her home at this stage.

He gave a short-tempered nod, looked at his watch, scribbled a few words in his note pad, took a brief check of her blood pressure and heart, and he and his entourage swept out of the room without even saying good-bye.

By now it was around eight, visiting hours were over, and ward 7A of St. Lucas Hospital was in complete silence. I switched off the big lights, leaving just the light above the washbasin, and moved my chair close to my mothers bed. She was dozing; in her hand she clutched a brand-new handkerchief Dia and I had given her. I sprinkled it and her sheets with 4711 eau de cologne, some thing she and her mother before her had enjoyed from childhood.

I looked down at her gaunt face, her eyes dark and sunken, and refreshed the washcloth for her. She woke up for a few moments and sighed.

Oh, I am so glad you are here. Please dont leave me anymore.

No, Mom, I cried, collapsing against her feeble chest. I will never leave you again. Ill sit with you until the end.

My mothers life companion, Hetty, had also been with her for the last few hours. Now she took my mothers hand, kissed it, and said good-bye, relieved that I would look after her for the rest of the night.

I had brought a big bag of magazines and newspapers I had not had time to read, and intended to settle down next to my mom. Suddenly, some thing told me to grab a pen and my notebook and start writing. It had been twelve years since my last book, but now I was inspired to commit to paper every moment of this experience. For four hours I sat there, writing by hand (some thing I had long since left behind in favor of the computer). It was an enormous relief.

Around midnight, I was very tired. Usually I am wide awake at that hour, but here in the quiet surroundings of the hospital it felt good to try and catch some sleep. I felt utterly worn out, so I climbed into a bed that had been brought for me and placed beside my mothers. I barely slept, waking every half hour to have a good look at my mother, placing my ear against her chest to make sure she was still breathing.

I woke suddenly at five oclock, unsure for a moment where I was, then got up and drove home. I was struck by the color of the sky, serene in pinks and purples. Well aware this time that I was behind the wheel, I did not rush, enjoying the quietness on the road. When I arrived at my own house my dogs greeted me excitedly, and I found notes every where from the people who live with me. I took a quick shower and checked my E-mail, confident that my mom would hang on to life for at least another day or two. But already at half past six I felt restless, worried that she might awake and fret at not finding me next to her.

DAY TWO. Wednesday, July 7, 1999

Today was not such a good day: Mom now barely spoke. I had brought with me a copy of a printed booklet I had compiled, a collection of my moms favorite German and Dutch poems about death, along with three pages I had written as my own offering. The cover was a tender picture of my mom and me during our happy days in Spain ten years before. Christopher, the sweet Singaporean houseboy who lives with us, had neatly bound them with a purple ribbon. The booklet was the idea of an artistic young lesbian friend of mine named Pauline; she spent two days on its layout and printing, creating a lovely memorial for my mother.

Next page