Introduction

I live in a lovely place. It is a small farm, just a few acres, but it is beautiful. I created this farm over many years, and it is still evolving, and will continue to for many years hence. I never intended to be a farmer and yet it feels right. I enjoy a connection to the land, to the animals here, and I am endlessly thrilled to make food; to feed people.

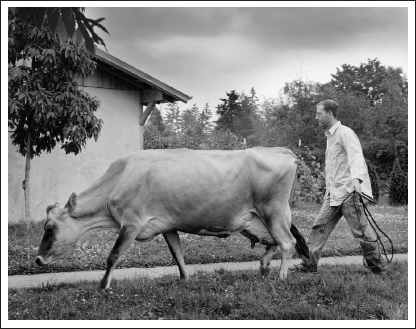

The primary product of this farm is cheese. A small herd of Jersey cows also call this bit of ground home. Twice a day they head down from the upper pastures to the barn. There I will meet them, milk them and in the hours and days to come transform that milk into cheese.

When I say that I live in a lovely place, I also mean place in the abstract sense. I work for myself; I have no boss. This is not to say that it is a perfect job, or one without challenges. Each day brings new setbacks and new rewards. This farm, this business, changes every year, sprawls in every direction seemingly without a plan. I pretend to control it, but often it controls me.

This is the story of a farm. It is the story of my journey from the city life of a restaurateur to my present life as a farmer. It is not a cookbook, although the preparation of food is discussed. It is not a how-to guide to farming, although much can be learned about farming from these pages. It is not a treatise on agriculture in America, although I certainly have opinions on the health and viability of small farms.

My wish for this book is to add a perspective on the food we eat: where our food comes from, what goes into producing it and how it was traditionally prepared. I would be thrilled if some who read this book quit their day jobs, moved out of the city and built small farms. I doubt, however, that this will happen, and I wouldnt necessarily recommend it. I would be content if the reader, while at the supermarket the next week, picks up a small round of cheese from a local farm, pauses and contemplates how it was made. If that reader looks at carrots at the farmers market next weekend and marvels at their existence, picks them up and smells the earth that they had come from hours before, that would bring a smile to my face.

When I was twenty-four years old I opened my first restaurant. It was a small, actually very small, ten-foot by twenty-foot, caf. With just four tables squeezed together and a minuscule kitchen on the side, this humble space represented the start of my career. I had worked as a waiter and a pastry cook around town and felt that I could run a restaurant better than my much more experienced bosses and coworkers. Despite this confidence, I really had no clue what I was up against and was immediately overwhelmed by the difficulties of owning and managing a business.

Every morning at four I would walk the two blocks from my small studio apartment in downtown Seattle to the caf and bake pastries in the manner of a home cook. The kitchen was tiny, the equipment of small scale and my volume of baked goods originally very limited; one pound cake, a couple of coffee cakes, four dozen biscuits. At seven in the morning the caf would open and I would sell the fresh pastries and coffee to the receptive locals who would line up daily. They could see into the small kitchen, see the mixer, watch the rolls come out of the oven and onto the counter in front of them. What was significant to me about this entire process was there was integrity; I bought butter and flour and baked it into pastries and handed it to people to eat right there. Yes, this is the description of every bakery the world over, but I thought, perhaps arrogantly, that no one was doing it so directly. I reached into the oven, pulled out a biscuit and placed it on a plate. I had made that biscuit, I had served it and the customer ate it. There were no cake mixes, no canned fillings, no waiters, no corporate offices. I sold goods for cash and then walked across the street to the bank and put the money in the bank. It was real and it was good. This influenced the way I would look at my world henceforth, though this simple and satisfying arrangement couldnt last.

As the caf grew to be more popular and therefore more profitable, I realized I could afford to buy a house and settle down, move out of my small studio in the city. If I could have afforded a home in the city, I most likely would have stayed in Seattle. Even then, twenty years ago, the price of real estate in the city was quite high and well out of my reach.

My universe at the time was the caf and my apartment, both in downtown Seattle. I began to look for less expensive places to live that had the luxury of space. Seattle is located on Puget Sound, an expansive protected body of water dotted with islands that extend northward to Canada. The island closest to downtown Seattle, and accessed by ferryboats that docked a few blocks from my apartment, is Bainbridge Island. Originally I checked out homes there, but found them to be too costly. South of Bainbridge Island is Vashon Island, accessed by state ferryboats as well, but much less conveniently; the dock is located in West Seattle, a long trek from downtown Seattle.

In addition to simply finding a home on Vashon Island cheaper than I could in Seattle, there was also the pull of nature. My impression at that time was that life would be easier in a small town, that life outside of the turmoil of a large city would be serene, orderly and tranquil. I confess that all these many years later I continue to fall into this flawed thinking. And so I began my search for a new home: I wanted more space than my humble apartment offered, situated far enough from the city to be affordable. I wasnt looking to become a farmer; the thought hadnt even crossed my mind. I just wanted a place where I could unwind after my grueling days at the caf.

I had never learned to drive and did not have a drivers license. I never really wanted a car; found them wasteful and expensive. I enjoyed my downtown city life. I walked to the market to buy produce for the caf, picked up flowers for my apartment, knew all the shopkeepers and lived a full, urban existence.

I would peruse the classified ads of the local newspaper, looking for homes to buy. My family ethos was rooted in the American dream: buy a house and you will be financially independent. I never doubted it, I never questioned it. I needed to buy a house to have a complete life. Whether I realized it or not, even then I was striving for self-sufficiency: start a business, use the proceeds to buy a house, live autonomously. Ive never expected my family to care for me in my old age, I intend to care for myself, and acquiring land and shelter was the next logical step.

I soon discovered that Vashon Island was a part of King County, the county of Seattle, and therefore had the same bus service. I could live outside of Seattle and ride the bus to work. I made a perfunctory review of the bus schedules and confirmed that there were buses that ran from downtown Seattle to the island, the buses boarding the ferryboats in the process. I couldnt really understand the schedules, knew nothing of the island and had never set foot on it, and yet proceeded to check out the local homes.