JOHN ARCHIBALD WHEELER

with

KENNETH FORD

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 1998 by John Archibald Wheeler and Kenneth Ford

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton 2000

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wheeler, John Archibald, 1911

Geons, black holes, and quantum foam: a life in physics / John Archibald Wheeler with

Kenneth Ford.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07948-7

1. Wheeler, John Archibald, 1911. 2. PhysicsHistory.

3. AstronomyHistory. 4. PhysicistsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Ford, Kenneth William, 1926. II. Title.

QC16.W48A3 1998

530.092dc21

[B]

97-44566

CIP

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

To the wonderful teachers, students, and colleagues who have

inspired and guided me over the years;

and

to the still unknown person(s) who will further illuminate the

magic of this strange and beautiful world of ours by discovering

How come the quantum? How come existence?

We will first understand how simple the universe is when we

recognize how strange it is.

CONTENTS

GEONS, BLACK HOLES, AND QUANTUM FOAM

HURRY UP!

ON MONDAY , January 16, 1939, I taught my morning class at Princeton University, then took a train to New York and walked across town to the Hudson River dock where the Danish physicist Niels Bohr was scheduled to arrive on the MS Drottningholm . Bohrwith whom I had worked a few years earlierwas coming to give some lectures at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and spend time with his friend Albert Einstein, then a professor at the Institute, and I had decided to greet him.

For a dozen years, Bohr and Einstein, probably the two most eminent physicists in the world at that time, had had a running debate on the meaning and interpretation of quantum mechanics, the subtle theory that governs motion and change in the subatomic realm. Bohr held that uncertainty and unpredictability are intrinsic features of the theory, and therefore of the world in which we live. Einstein embraced a deterministic worldview; he could not believe that God played dice. Over the years, Einstein had proposed various thought experiments that at first appeared to expose cracks in the structure of quantum mechanics, and Bohr had been able to turn every one of them around to show more clearly than ever that his Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory, with its fundamental probability, stood fast. As it turned out, however, nuclear fission, not the mysteries of the quantum, occupied most of Bohrs time during his visit. Just before embarking from Denmark, he had learned of this new phenomenon, and he had been thinking hard about it all the way across the ocean.

Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in Brussels, one of the places where they carried on their famous debates, 1930.

(Photograph by Paul Ehrenfest, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segr Visual Archives.)

I was not the only one who decided to welcome Bohr personally. While I was waiting on the dock, who should turn up but the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi and his wife, Laura, who, with their two children, had arrived in the United States only two weeks earlier. Enrico, short, muscular, and intense, was a man of habit and order whose mind never rested. Laura, dark and pretty, had studied engineering and science before marrying Enrico and would later establish herself as a writer. As the story jokingly puts it, Fermi, after receiving his Nobel Prize in Sweden in December 1938, became lost on his way back to Italy and ended up in New York. In fact, they wanted to get away from the Fascism of their native ItalyLaura was Jewishand the itinerary had been carefully and quietly planned to bring them to New York, where a professorship at Columbia University awaited Enrico.

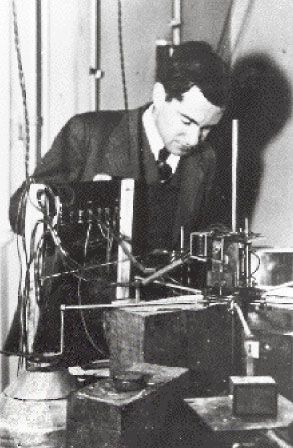

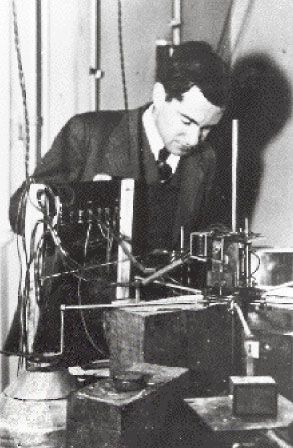

Otto Frisch in his Copenhagen laboratory, 1936.

(Courtesy of Niels Bohr Archive, Copenhagen.)

Fermi came to the dock to invite Bohr to spend a day with him in New York before going to Princeton. The news of fission that Bohr had in his head would be of consuming interest to Fermi, himself a nuclear pioneer. But by chance, it would be I, not Fermi, who would become the first on these shores to hear of it.

Bohr learned of fission on January 3, four days before he and his son Erik boarded the train in Copenhagen for Gothenburg, the MS Drottningholm s embarkation point. Otto Frisch, a German emigr physicist working at Bohrs University Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen, sought out Bohr to inform him of the postulate of fission that he (Frisch) and his aunt, Lise Meitner, had devised in the last week of December to explain puzzling results found by the German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in their Berlin laboratory. When Hahn and Strassmann bombarded uranium with neutrons (subnuclear particles with no electric charge), they found evidence that the element barium was created. Since barium is far removed from uranium in the periodic table and has a much lighter nucleus, they could not make sense of this result. Hahn wrote to Meitner in Sweden, describing the puzzle, for she had been his longtime colleague in Berlin before leaving Germany to escape persecution, and was trained in physics. When her nephew Frisch came for a holiday visit, they took a Christmas Eve walk in the woodshe on skis and she on footto ponder the Berlin results. Suddenly it became clear to them. The uranium nucleus must be breaking into large fragments, resulting in the nuclei of other elements, including sometimes the nucleus of barium.

Lise Meitner in animated discussion with the Italian physicist Emilio Segr in Copenhagen, 1937.

(Courtesy of Niels Bohr Archive, Copenhagen.)

When Bohr heard Frisch offer this explanation, his reaction was swift and positive. Oh what idiots we all have been! he said. Oh but this is wonderful! This is just as it must be! Bohrs was a mind prepared. He knew as much as any person alive about atomic nuclei, and could see at once that fission made senseeven though, up to that point, he and other nuclear physicists had imagined that at most only tiny fragments could break off from a nucleus.

In addition to his son Erik, Bohr brought with him a young colleague, Lon Rosenfeld. Rosenfeld was to serve as Bohrs sounding board and scribe, to help Bohr formulate his ideas, and to capture for publication whatever sparks might fly when Bohr and Einstein put their heads together. Throughout the nine-day ocean crossing, fission was probably more on Bohrs mind than the upcoming meetings with Einstein. He and Rosenfeld discussed it incessantly. (Bohr had a blackboard installed in his stateroom, to facilitate their talks.) By the time Bohr shook hands with me and the Fermis on the dock, he had a pretty good idea of a direction to go in to give a theoretical account of fission. That is what would occupy us intensely for the next few months.