ALSO BY JOHN W. MOFFAT

Reinventing Gravity

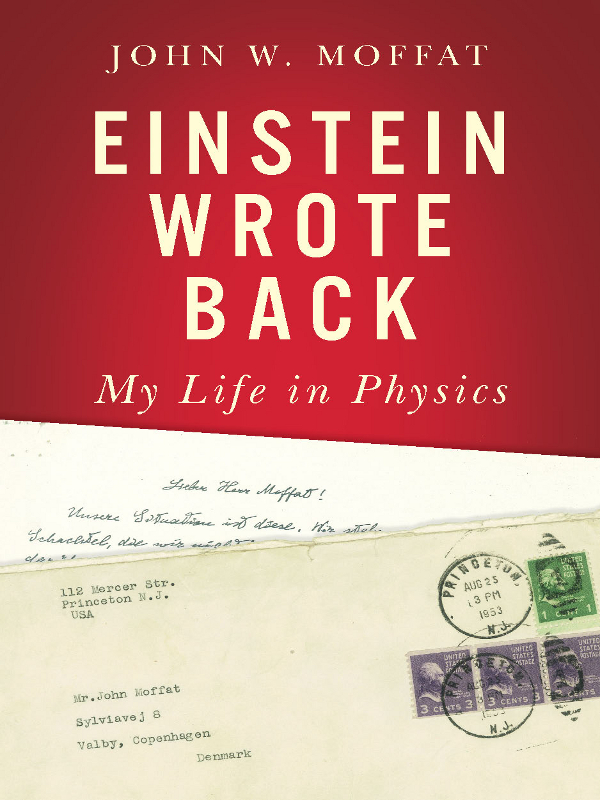

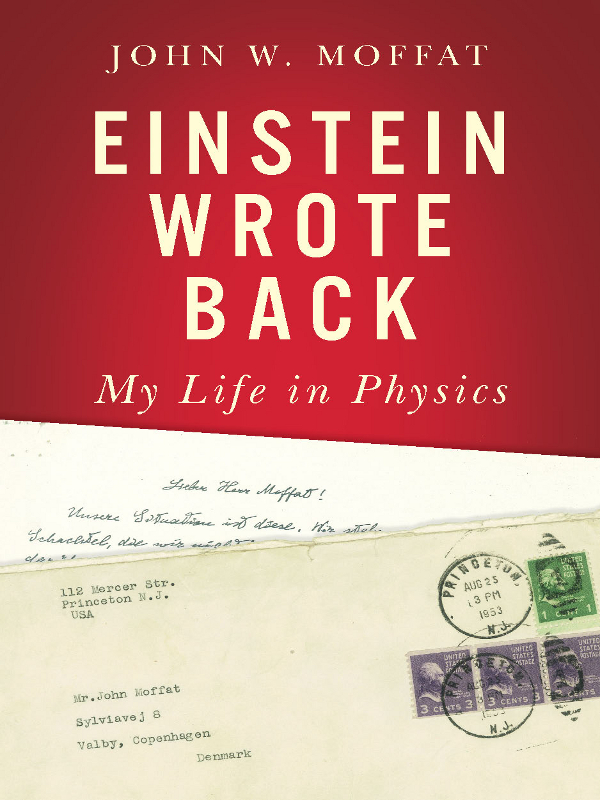

Einstein Wrote Back

John W. Moffat

EINSTEIN WROTE BACK

My Life

in Physics

THOMAS ALLEN PUBLISHERS

TORONTO

Copyright 2010 John W. Moffat

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any meansgraphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systemswithout the prior written permission of the publisher, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Moffat, John W., 1932

Einstein wrote back / John W. Moffat.

ISBN 978-0-88762-615-9

1. Moffat, John W., 1932 . 2. Moffat, John W., 1932 Friends and associates.

3. PhysicistsCanadaBiography. 4. PhysicsHistory20th century. I. Title.

QC16.M64A3 2010 530.092 C2010-903799-5

Editor: Janice Zawerbny

Jacket design: Michel Vrna

Jacket photo of Einstein letter: Copyright Albert Einstein Archives,

Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Published by Thomas Allen Publishers,

a division of Thomas Allen & Son Limited,

145 Front Street East, Suite 209,

Toronto, Ontario M5A 1E3 Canada

www.thomasallen.ca

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of The Ontario Arts Council for its publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

We acknowledge the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

1 2 3 4 5 14 13 12 11 10

Printed and bound in Canada

Again to Patricia,

whose dedication made this book possible,

and to Sandra, Tina,

Derek and Tessa

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Child of War

CHAPTER 2

Two Paths Diverged

CHAPTER 3

Niels Bohr

CHAPTER 4

Albert Einstein

CHAPTER 5

Erwin Schrdinger

CHAPTER 6

Fred Hoyle

CHAPTER 7

The Einstein Fest

CHAPTER 8

Wolfgang Pauli

CHAPTER 9

Paul Dirac

CHAPTER 10

Abdus Salam

CHAPTER 11

Imperial College London

CHAPTER 12

Baltimore

CHAPTER 13

CERN and Particle Physics

CHAPTER 14

Princeton and Oppenheimer

CHAPTER 15

Toronto

T HROUGH the large picture window in my office at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, I have a view of Silver Lake in a nearby park.While pondering the mysteries of the universe, I often watch the swans gliding back and forth across the lake, and the children in the playground on the other side.

The Instituteaffectionately called PI was founded by Mike Lazaridis, the inventor of the BlackBerry, whose company, Research in Motion (RIM), is headquartered in Waterloo. Lazaridis has contributed generous funds to creating PI, where over one hundred theoretical physicists from around the world spend their time following impractical dreams: searching for quantum gravity, understanding the beginnings of the universe and probing the quantum nature of matter. As the name of the Institute implies, we physicists who work there are out on the perimeter or the cutting edge of fundamental physics. PI is an ideal place for me to be, as since my unusual beginning in physics, I have been mostly involved in searching for new ways to come to a fundamental understanding of the universe. This kind of physics is often referred to as outside the box. Those of us who practise it think about physics in an unconventional way, attempting to view old problems in novel ways, or to ask unusual questions that may bear fruit in unexpected ways. Yet ultimately we always hope to relate our speculative theories to the reality of nature by comparing the predictions of our theories with experiments and observations.

Occasionally I stare out my window at Silver Lake and think about the bizarre way my life unfolded, eventually leading me to this place. In my peripatetic and traumatic childhood in Denmark, England and Scotland during and after the Second World War, I showed little aptitude for mathematics and scienceso little, in fact, that I was not even allowed to enter university. Instead, I set my sights on becoming an abstract painter, an almost impossible career choice in the immediate postwar years. But then something peculiar happened to me to change drastically the course of my life. Within little more than a year, I vaulted from working at odd jobs in Copenhagenwindow cleaner, delivery boy, mail sorterto entering the Ph.D. program in physics at Trinity College, Cambridge.

How did this happen? What did it mean? Colleagues as well as my family have often encouraged me to write about my early life and the unusual way that I entered physicsand to put down on paper the many anecdotes with which I had regaled them, about the famous physicists of the twentieth century that I had the good fortune to meet. When I ask myself how I became a physicist in the first place, and how I managed to remain outside the box of conventional physics, working on truly fundamental questions of nature throughout so much of my career, my thoughts keep returning to the difficulties of my childhood, the love of beauty that inspired my first career as an artist and the influence of those giants of physics, whose kindness and help encouraged me on my way.

Physicists explore the nature of the universe, from its farthest edges to the smallest constituents of matter. In the twentieth century, with amazing improvements in telescopes and many space missions, we were able to expand our understanding of the evolution of the universe back almost to its beginning. This is a remarkable development in the history of science, because from the Greeks up until the beginning of the twentieth century, our astrophysical investigations were restricted to the much smaller universe of our solar system and our galaxy. We have also made great strides in penetrating the universe of the very small, and gradually the mysteries of the structure of matter are being revealed to us. Cracking the quantum code of matter is only possible through extraordinarily high-energy accelerators such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the largest particle physics laboratory in the world, at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), near Geneva, which began operation in 2010. We are on the threshold of exciting new discoveries in the realm of particle physics, which will help unravel the mysteries of the nature of matter.

Theoretical physicists attempt to build models of nature based on mathematics, and experimental physicists provide the data that can test the ideas and models proposed by the theoretical physicists. In practice there is an interplay between theory and experiment. Often, successful research in theoretical physics starts with a well-grounded knowledge of experimental data, building up from this data into a theory. Another important area of physics is industrial physics, where developing new technologies eventually leads to advances in computers, televisions, cellphones, medical diagnostics and many other electronic applications. All of these devices grew out of abstract theoretical ideas and their subsequent verification by experimental physics.

Next page