Louise Erdrich

Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country

for Nenaaikiizhikok and her brothers and sisters

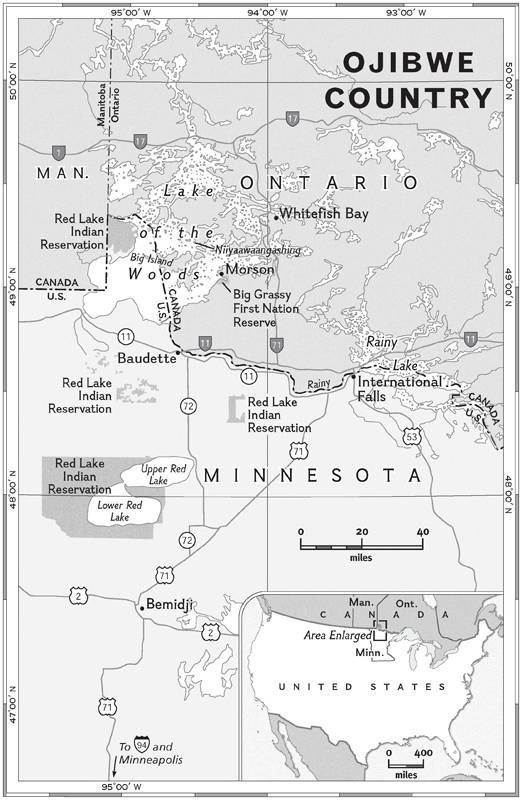

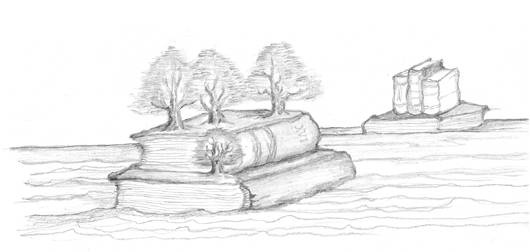

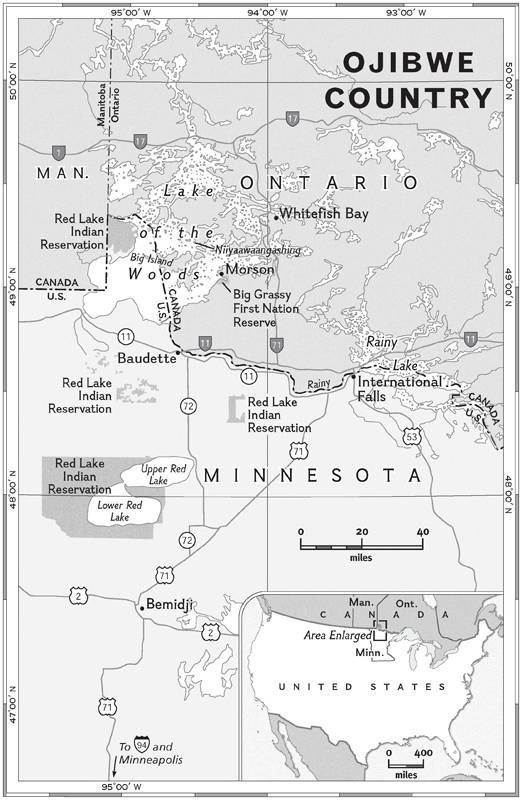

My travels have become so focused on books and islands that the two have merged for me. Books, islands. Islands, books. Lake of the Woods in Ontario and Minnesota has 14,000 islands. Some of them are painted islands, the rocks bearing signs ranging from a few hundred to more than a thousand years old. So these islands, which Im longing to read, are books in themselves. And then there is a special island on Rainy Lake that is home to thousands of rare books ranging from crumbling copies of Erasmus in the French and Heloises letters to Abelard dated MDCCXXIII, to first editions of Mark Twain (signed) to a magnificent collection of ethnographic works on the Ojibwe that might help explain the book-islands of Lake of the Woods.

I am not traveling alone. First my eighteen-month-old and still nursing daughter and I will pop over the Canada-U.S. border and visit Lake of the Woods and the lands of her namesake, her grandmother. Then well dip below the border and travel east to Rainy Lake. Well put about a thousand miles on our car and several hundred on other peoples boats. Im forty-eight years old and I cant travel aimlessly. I always seem to have a question that I would like to answer. Increasingly, too, it is the same question. It is the question that has defined my life, the question that has saved my life, and the question that most recently has resulted in the questionable enterprise of starting a bookstore. The question is: Books. Why? The islands are really incidental. Im not much in favor of them. I grew up on the Great Plains. Im a dry-land-for-hundreds-of-miles person, but Ive gotten mixed up with people who live on lakes. And then these islands have begun to haunt me, especially the one with all of the books.

Mazinaiganan is the word for books in Ojibwemowin or Anishinaabemowin, and mazinapikiniganan is the word for rock paintings. Ojibwemowin is the Algonquin language originally spoken by the Ojibwe people living throughout Michigan, Minnesota, Ontario, Manitoba, and on into North Dakota. As you can see, both words begin with mazin. It is the root for dozens of words all concerned with made images and with the substances upon which the images are put, mainly paper or screens. As the Ojibwe people began to watch television and go to movies, the word came in handy. Mazinaatesewigamig. Movie Theater. Mazinaatesijigan. Television set. They had a root word ready to make into a verb way back when Edward Curtis and later Ernest Oberholtzer came to photograph them. Mazinaakizo. To be photographed. (Nothing about stealing souls in the word mazinaakizo. Photographers did not take Ojibwe souls, it wasnt that easy. Soul theft required the systematic hard work of inventive humiliations and abuse by the government and by Catholic nuns and priests.)

The Ojibwe had been using the word mazinibaganjigan for years to describe dental pictographs made on birchbark, perhaps the first books made in North America. Yes, I figure books have been written around here ever since someone had the idea of biting or even writing on birchbark with a sharpened stick. Books are nothing all that new. People have probably been writing books in North America since at least 2000 B.C. Or painting islands. You could think of the lakes as libraries. 2000 B.C. is only the date of the oldest archaeological evidence found in the area we are going to visit. Traditional Anishinaabe people find the land-bridge theory a concept convenient to non-Indians and insist theyve been here forever. And in truth, since the writing or drawings that those ancient people left still makes sense to people living in Lake of the Woods today, one must conclude that they werent the ancestors of the modern Ojibwe. They were and are the modern Ojibwe.

Books. Why?

Because our brains hurt.

How a Mother Packs

For a week before I leave on any trip, I am distracted and full of cares. Just at the last minute, I always find myself doing things that I have put off for months, even years. I always change my will, then clean out cabinets and file old letters. I make certain that we all have sufficient underwear, that money and phone numbers are in relevant hands, the dogs vaccinated for Lyme disease, the manuscript of the last book is in production, the baby has her shots. Then I get more specific to the trip itself. I read books on pictographs and decide which notebooks to take along. Change the oil in the car. Make sure that my older daughters have postcards and shampoo. I buy tobacco not to smoke but to offer to the spirits of the lake and the spirits of the rock paintings we will visit. I gather gifts for the paintings a ribbon shirt, some red cloth, sage bundles. I purchase 124 disposable diapers and one of those baby harnesses I see mothers using in malls. If the baby goes over the edge of a boat or off an island, I picture myself hauling her right up. I go over plans for house-sitting and financial reports and make certain that our bookstore doesnt need me. There are so many small things. It is the small things that will consume me. The sunblock. The elms that must be treated with fungicide. The shoes. The many sizes and types of shoes girls wear all through their lives. I tell myself that God and meaning are in the small things as well as in the vast. But where in the wilderness of shoes is God? In the laces? The rubber bumpers? The heels that swiftly rise at age twelve?

On the other hand, none of this matters at all. The attention to details is just a way to stave off facing the truth. I hate leaving home.

Home

My 103-year-old house is surrounded by great trees. I have named each one of them. There is Guarding Elm that leans and tosses to the west, just beyond the blue gate. Tiny Offshoot of the Great Wahpeton Maple grows alongside, only six feet tall. It is still shaped like a drumstick. I grew it from a seedling that took root in one of my mothers flowerpots. Awkward and Shy are the elms that flank these two trees and Old Stalwart, biggest tree in the neighborhood, stands guard around the corner, in front of the house. Pensive Lover and Serene Darling, Haywire and Entire Trust are the locust trees that have sprung up in a ragged line along the edge of the yard. I have great admiration for these trees as they seem unkillable and their fronds of tossing leaves provide an ever shifting and trembling pattern of shadows on the old cream-colored walls inside our house. Also, they leaf out last of all and lose their leaves last, too, every fall, providing one final bank of burnished glory before the blastoff into winter.

Our house was built as a wedding gift for a fathers much-adored daughter. His house, same layout, still stands next door. This house was built when the lake to our east was still a marsh, before it was dredged. Our house even looks a bit like a wedding cake, trimmed with spindle rails, bows carved over the window, egg and dart molding, and a couple of round peephole windows. Perhaps one day well attach a cheesy fifteen-foot plastic bride and groom to the roof. During the sixties, our house was gutted and became a rooming house, then a duplex. The interior lost its charming details and became just peculiar. Guests have seen a ghost on the top floor and the girls hear it walking. They believe he is a confused man, and thats what we call him. Sometimes, when one of my older daughters is gone for a while, the baby and I will sleep in her room so that the ghost of The Confused Man does not take up residence. I describe all of this because there can be no traveling unless there is a leave-taking. And the traveling is all the more in earnest if the leaving is difficult. For me, leaving hurts. This is the dwelling of four essential beings. My daughters. Even when they are not here, all of their things are here. We dont mean to become attached to things, but we do and rather than live in complete clutter, we are always culling, throwing, giving.