Louise Erdrich - Four Souls

Here you can read online Louise Erdrich - Four Souls full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Harper Perennial, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Four Souls

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper Perennial

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Four Souls: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Four Souls" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Four Souls — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Four Souls" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Louise Erdrich

Four Souls

She threw out one soul and it came back hungry.

Kaanish inaa indinaawemaaganitog,

Asemaa ingii pagichige chi otaapin aawat atasookanag.

Aya ii onji wegonen ina pichi tazhimag kaaye

pichi ozhibiiwag kaagi aaya sig.

Kaawiin wiin aawiya nibaapinenimaasi.

Pepekaan inenimishig.

Miigwech,

Weweni sago.

~ ~ ~

ONE. The Roads Nanapush

FLEUR TOOK the small roads, the rutted paths through the woods traversing slough edge and heavy underbrush, trackless, unmapped, unknown and always bearing east. She took the roads that the deer took, trails that hadnt a name yet and stopped abruptly or petered out in useless ditch. She took the roads she had to make herself, chopping alder and flattening reeds. She crossed fields and skirted lakes, pulled her cart over farmland and pasture, heard the small clock and shift of her ancestors bones when she halted, spent of all but the core of her spirit. Through rain she slept beneath the carts bed. When the sun shone with slant warmth she rose and went on, kept walking until she came to the iron road.

The road had two trails, parallel and slender. This was the path she had been looking for, the one she wanted. The man who had stolen her trees took this same way. She followed his tracks.

She nailed tin grooves to the wheels of her cart and kept going on that road, taking one step and then the next step, and the next. She wore her makizinan to shreds, then stole a pair of boots off the porch of a farmhouse, strangling a fat dog to do it. She skinned the dog, boiled and ate it, leaving only the bones behind, sucked hollow. She dug cattails from the potholes and roasted the sweet root. She ate mud hens and snared muskrats, and still she traveled east. She traveled until the iron road met up with another, until the twin roads grew hot from the thunder and lightning of so many trains passing and she had to walk beside.

The night before she reached the city the sky opened and it snowed. The ground wasnt frozen and her fire kept her warm. She thought hard. She found a tree and under it she buried the bones and the clan markers, tied a red prayer flag to the highest branches, and then slept beneath the tree. That was the night she took her mothers secret name to herself, named her spirit. Four Souls, she was called. She would need the name where she was going.

The next morning, Fleur pushed the cart into heavy bramble and piled brush over to hide it. She washed herself in ditch water, braided her hair, and tied the braids together in a loop that hung down her back. She put on the one dress she had that wasnt ripped and torn, a quiet brown. And the heavy boots. A blanket for a shawl. Then she began to walk toward the city, carrying her bundle, thinking of the man who had taken her land and her trees.

She was still following his trail.

Far across the fields she could hear the city rumbling as she came near, breathing in and out like a great sleeping animal. The cold deepened. The rushing sound of wheels in slush made her dizzy, and the odor that poured, hot, from the doorways and windows and back porches caused her throat to shut. She sat down on a rock by the side of the road and ate the last pinch of pemmican from a sack at her waist. The familiar taste of the pounded weyass, the dried berries, nearly brought tears to her eyes. Exhaustion and longing filled her. She sang her mothers song, low, then louder, until her heart strengthened, and when she could feel her dead around her, gathering, she straightened her back. She kept on going, passed into the first whitened streets and on into the swirling heart of horns and traffic. The movement of mechanical, random things sickened her. The buildings upon buildings piled together shocked her eyes. The strange lack of plant growth confused her. The people stared through her as though she were invisible until she thought she was, and walked more easily then, just a cloud reflected in a stream.

Below the heart of the city, where the stomach would be, strange meadows opened made of stuff clipped and green. For a long while she stood before a leafless box hedge, upset into a state of wonder at its square shape, amazed that it should grow in so unusual a fashion, its twigs gnarled in smooth planes. She looked up into the bank of stone walls, of brick houses and wooden curlicued porches that towered farther uphill. In the white distance one mansion shimmered, light glancing bold off its blank windowpanes and turrets and painted rails. Fleur blinked and passed her hand across her eyes. But then, behind the warm shadow of her fingers, she recovered her inner sight and slowly across her face there passed a haunted, white, wolf grin.

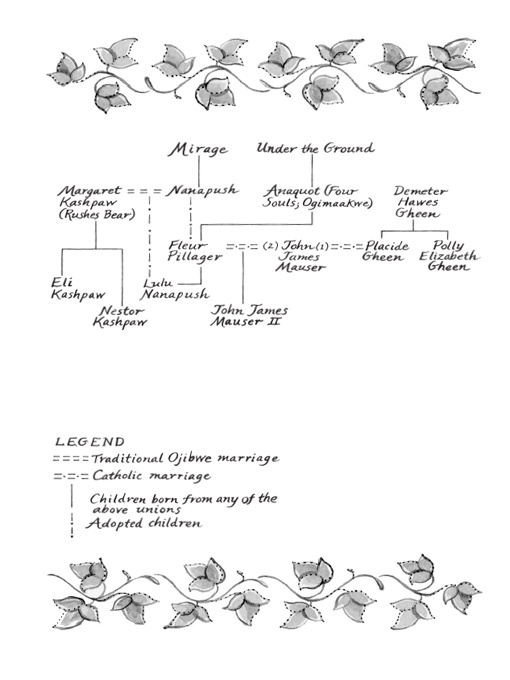

SOMETIMES an old man doesnt know how he knows things. He cant remember where knowledge came from. Sometimes it is clear. Fleur told me all about this part of her life some years after she lived it. For the rest, though, my long talks with Father Damien resulted in a history of the great house that Fleur grinned up at that day. I pieced together the story of how it was formed. The priest and I sat long on the benches set against my little house, or at a slow fire, or even inside at the table carefully arranged on the linoleum floor over which Margaret got so particular. During those long conversations Father Damien and I exchanged rumors, word, and speculation about Fleurs life and about the great house where she went. What else did we have to talk about? The snow fell deep. The same people lived in the same old shacks here. Over endless games of cards or chess we amused ourselves by wondering about Fleur Pillager. For instance, we guessed that she followed her trees and, from that, we grew convinced that she was determined to cut down the man who took them. She had lived among those oak and pine trees when their roots grew deep beneath her and their leaves thick above. Now he lived among them, too, only he lived among them cut and dead.

Here is how all that I speak of came about.

During a bright thaw in the moon of little spirit, an Ojibwe woman gave birth on the same ground where, much later, the house of John James Mauser was raised. The ridge of earth was massive, a fold of land jutting up over a brief network of lakes, flowing streams, rivers, and sloughs. That high ground was a favorite spot for making camp in those original years before settlement, because the water drew game and from the lookout a person could see waasa, far off, spot weather coming or an enemy traveling below. The earth made chokecherries from the womans blood spilled in the grass. The baby would be given the old name Wujiew, Mountain. After a short rest he was tied onto his mothers back and the people moved on, moved on, pushed west.

From that direction, the place where the dead follow after their names, came wheat in a grasshopper year, hauled out green and fermenting to feed the working crews. A city was raised. Gakaabikaang. Place of the falls. Wood framed. Brick by brick. The best brownstone came from an island in the deep cold northern lake called Gichi gami. The ground of the island had once been covered with mammoth basswood that scented the air over the lake, for miles out, with a swimming fragrance of such supernal sweet innocence that those first priests who came to steal Ojibwe souls, penetrating deeper into the heart of the world, cried out not knowing whether God or the devil tempted them. Now the island was stripped of trees. The dug quarry ran a quarter mile in length. From below the soil, six-by-eight blocks were drilled and hand-cut by homesick Italians who first hated the state of Michigan and next Wisconsin and felt more lost and alien the farther they worked themselves into this country. Every ten hours, night and day, the barge arrived for its load and the crane at the waters edge was set into operation. The Italians slept in shifts and were troubled in their dreams, so much so that one night they rose together in a storm of beautiful language and walked onto the barge to ride along with their own hewn rock toward the farthest shore forfeiting wages. Still, there was more than enough brownstone quarried, cut, hand-finished, shipped, and hauled uphill, for the construction of the house to continue.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Four Souls»

Look at similar books to Four Souls. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Four Souls and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.