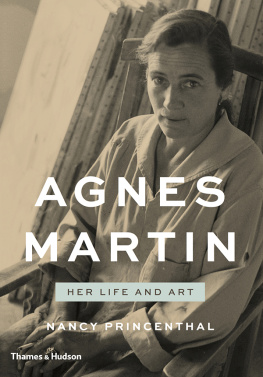

About the Author

Nancy Princenthal is a New York-based critic and former Senior Editor of Art in America, for which she continues to write regularly. Other publications to which she has contributed include Artforum, Parkett, the Village Voice and the New York Times. She is a co-author of two recent books on leading women artists, including The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium. She has taught at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Princeton University, Yale University, Rhode Island School of Design, Montclair State University and elsewhere, and is currently on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Women Artists

The Linda Nochlin Reader

New York Mid-Century

Post-War Capital of Culture, 1945-1965

Art Since 1900

Georgia OKeeffe

See Our Website

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

To be abstracted is to be at some distance from the material world. It is a form of local exaltation but also, sometimes, of disorientation, even disturbance. Art at its most powerful can induce such a state, art without literal content perhaps most potently. Agnes Martin, one of the most esteemed abstract painters of the second half of the twentieth century, expressed and, at times, dwelled in the most extreme forms of abstraction: pure, silencing, enveloping, and upending.

Martins mature paintings (she destroyed most of her early work) are incontrovertibly right, in the sense that they convince us that not a single preliminary decision or incident of execution could have been changed without damage. Composed of the simplest elements, including ruled, penciled lines and a narrow range of forms grids, stripes, and, very occasionally, circles, triangles, or squares and painted in a limited palette on canvases that are always square, they reveal an esthetic sense that is, as her friend Ann Wilson said, the visual equivalent of perfect pitch.

Martin called her creative source inspiration, and she said that the paintings came to her as visions, complete in every detail, and needed only to be scaled up before being realized. (This scale shift generally required bedeviling computation; sheets densely covered in calculations attest to the trouble it caused.) It is possible to think of such a refined esthetic sense as savant-like or akin to a religious vocation: an attunement to qualities commonly imperceptible. Such acute sensibility is not rare, but many artists who have a refined visual sense find it a liability, threatening to equate the practice of their art with the design of their homes or the selection of their wardrobes, all elegant and graceful. Martin wasnt like that. She was capable of the most robust gaucheries. Even when she was wealthy, her choices of domestic furnishings and personal attire seem to have been utterly free of the standards that guided her artwork. But she was a ruthless judge of her own painting, discarding the many examples that failed her vision, and her acuity allowed her to see concatenations of line and color to an order of exactitude, surpassing common perception with ease, that can only be called transcendent.

That is not to say that her motivation, or her world view, were mystical. Martins ruled lines resonated with the hum of the physical world, and while she resolutely denied that her paintings contained references to the landscape, seascape, weather, or natural light (notwithstanding the many titles of her works that suggest such associations, most of which she later attributed to well-meaning but misinformed friends), her work is inarguably grounded in visual experience. Moreover, the work is meant to express universal emotional and existential states emphatically not those corrupted by lived, personal events. The states she represented and these in later years increasingly provided titles, unquestionably of Martins choosing are rarefied, ideal conditions: happiness, joy, and, especially, innocence. These titles, and the paintings they name, guard against the vulgarities of everyday life. Martins work, then, not only channels the visual and psychic abundance of the world but also filters it, relieving it of impurities.

As she stated often in the talks and lectures she started to deliver in the 1970s, many of which have since been published, the sense of self to which she aspired was egoless and devoid of pride, and her paintings can be seen to reflect that commitment in their refusal of either bravura execution or centered composition. At the same time, and again paradoxically, much of Martins work suggests a system of boundaries. In more cases than not, the penciled lines dont go to the canvass edge, and the earliest grids were set off by framing lines that echoed the canvases edges. And yet, exhibiting ones artwork, to which Martin was firmly devoted, is sure to breach such boundaries it is a public act, requiring pride and confidence. She made art to be seen by a wide audience, and she believed it was incomplete without the viewers response.

If it is hard to reconcile conflicting aspects of Martins work and character, it is because her internal life was deeply fragmented. By adulthood, she had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia; she was hospitalized several times and was treated for the illness, with both talk therapy and medication, throughout much of her life. Admiring accounts of her capacity for extended periods of preternatural calm might also point to the catatonia from which she occasionally suffered. As is often the case with schizophrenia, Martin was subject to auditory hallucinations, and although the voices she heard didnt tell her what to paint they seemed to steer clear of her work the images that came to her through inspiration were fixed and articulate enough to suggest a relationship between visions and voices: she heard and saw things that others didnt.

The pencil that was always in her hand when she began a painting, calculating its rhythms and transcribing her vision, may also be said to have transcribed her thought; in a sense she wrote her work. Born into a generation trained in penmanship (she was for many years a teacher of young children) and much given to handwritten letters, homilies, speeches, and poems, Martin carried that graphic impulse into her painting, where it met the geometric structures and color harmonies shaped by visual inspiration. The sense of hyper-connectedness that is a feature of paranoia may also be seen in Martins formal choices, the grid in particular. Representing the structure of interconnection, the grid in common parlance names an international communication system and a map of power. At once electric, alive, and dangerous, it is also supremely orderly and harmonious.

Without question, such speculation is hazardous. Creativity and active psychosis are incompatible; common sense tells us it is nearly impossible to work when youre seriously ill, and luckily Martin was not acutely ill often enough to prevent her production of a very substantial body of work. Just as it would be wrong to call her a mystic, it would be a gross error to see in her work symptoms of illness. Even less was it a cure. Moreover, mental illness is a moving target. In the 1960s, under the reign of orthodox psychoanalysis, schizophrenia (like all forms of mental illness) was treated, literally, as narrative. It was understood to be the result of a persons circumstances, and it was believed to be curable by telling the story of those circumstances, with honesty and feeling. At the same time in the sixties art was stripped of personality, of narrative, of expression, indeed of any information extrinsic to an exploration of arts own boundaries, of its function as a language. Fifty years later, these positions have flipped. Psychosis is now treated most successfully (or so says current wisdom and healthcare policy) with medication; early life experience and parental failure are not widely believed to be the most important contributing factors to schizophrenia. On the other hand, artists have lately been urged to get out in front of their work, to talk about its meaning and its sources, and their own origins as well.

Next page