Miranda Carter - George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I

Here you can read online Miranda Carter - George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Random House of Canada, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House of Canada

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

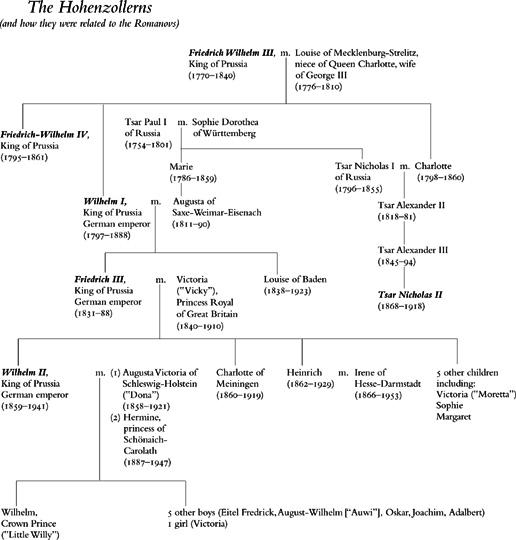

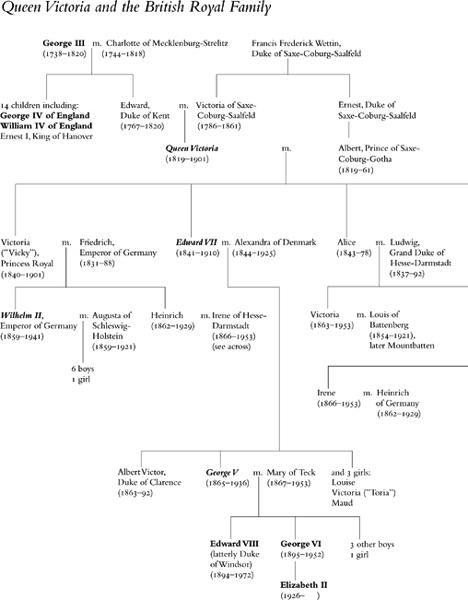

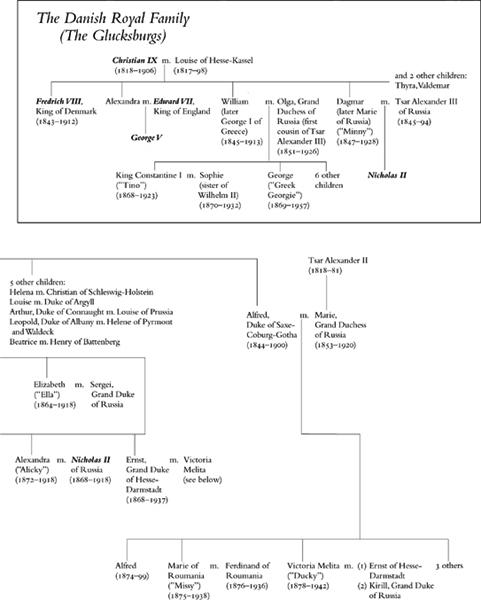

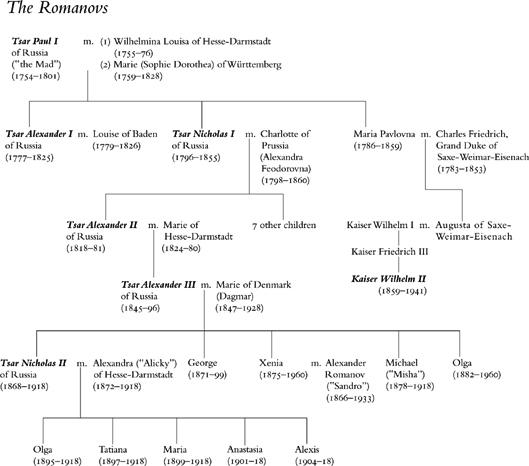

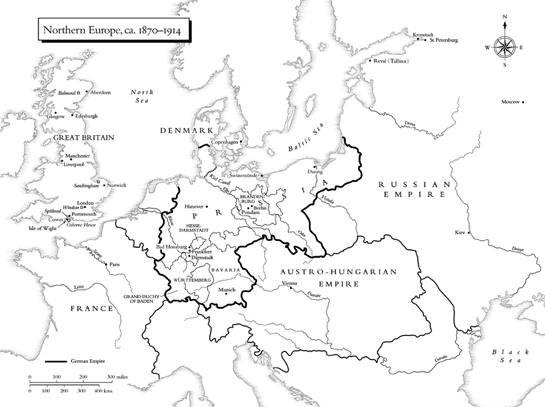

Starred Review The slippery slope into horrific armed conflict is a tale often told about World War I, but this authors take on the antecedents of the European war of 191418 is distinct. Carter views the shifting alliance entanglements of the Great Powers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and especially the growing animosity and rivalry between Britain and Germany, with particular focus on the attitudes and actions of three royal first cousins: Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, and King George V of Great Britain (who also reigned as emperor of India, hence the books title reference to three emperors). Rich in concrete detail, elegant in style, and wise, fresh, and knowledgeable in interpretation, the authors account observes a profound anachronism at play: that these three monarchs, in what they didnt realize were the waning days of the institution of monarchy, handled foreign diplomacy as if it were a family business. Despite the reality of growing fissures separating their countries, each emperor continued to paper over the cracks with cousinly gestures, each increasingly irrelevant. Europe plunged over the precipice of war in August 1914, revealing in stark terms the inability of royal familial ties to control and contain national disagreements; as the author has it, the fact that Wilhelm, Nicholas, and George were out of touch with actual politics could not have been more apparent. An irresistible narrative for history buffs. --Brad Hooper

ReviewPraise for Miranda Carters George, Nicholas, and Wilhelm:

Miranda Carter has written an engrossing and important book. While keeping her focus on the three cousins and their extended families, she skillfully interweaves and summarizes all important elements of how the war came about...Carter has given us an original book, highly recommended. ---_The Dallas Morning News_

Masterfully crafted. . . Carter has presented one of the most cohesive explorations of the dying days of European royalty and the coming of political modernity. . . Carter has delivered another gem. --_Bookpage_

Ms. Carter writes incisively about the overlapping events that led to the Great War and changed the world. . . George, Nicholas, and Wilhelm is an impressive book. Ms. Carter has clearly not bitten off more than she can chew for she -- as John Updike once wrote of Gunter Grass -- chews it enthusiastically before our eyes. --The New York Times

An irresistably entertaining and illuminating chronicle . . . Readers with fond memories of Robert Massie and Barbara Tuchman can expect similar pleasures in this witty, shrewd examination of the twilight of the great European monarchies. Publishers Weekly

A wonderfully fresh and beautifully choreographed work of history. Craig Brown, Mail on Sunday

A hauntingly tempting proposition for a book . . . The parallel, interrelated lives of Kaiser Wilhelm II, George V, and Nicholas II are . . . a prism though which to tell the march to the first World War, the creation of the modern industrial world and the follies of hereditary courts and the eccentricities of their royal trans-European cousinhood . . . An entertaining and accessible study of power and personality. Simon Sebag Montefiore, _Financial Times

_

Carter draws masterful portraits of her subjects and tells the complicated story of Europes failing international relations well . . . A highly readable and well-documented account. Margaret MacMillan, _The Spectator

_

I couldnt put this book down. The whole thing really lives and breathes and its very funny. That these three absurd men could ever have held the fate of Europe in their hands is a fact as hilarious as it is terrifying. Zadie Smith

[An] enterprising history of imperial vicissitudes and royal reversals. --The New York Times Book Review

Miranda Carter: author's other books

Who wrote George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.