clementine hunter

her life and art

Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS  BATON ROUGE

BATON ROUGE

clementine hunter

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Cane River National Heritage Area and to the Jack and Ann Brittain family for supporting the publication of this book.

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2012 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

DESIGNER : Michelle A. Neustrom

TYPEFACE: Whitman, text; Copse, display

PRINTER : McNaughton & Gunn, Inc.

BINDER : Acme Bookbinding

The Cane River Art Corporation, Natchitoches, Louisiana, holds the copyright to all Hunter images and granted permission to reproduce the paintings by Clementine Hunter appearing in this book.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Shiver, Art, 1946

Clementine Hunter : her life and art / Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8071-4878-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-4879-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-4880-8 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-4881-5 (mobi) 1. PaintersUnited StatesBiography. 2. African American paintersBiography. I. Hunter, Clementine Criticism and interpretation. II. Title.

ND237.H915S55 2013

759.13dc23

[B]

2012011755

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Contents

For Our Parents

Geneva and Frank Shiver

Grace and R. T. Whitehead

Foreword

Proper study and appreciation of the life and art of Clementine Hunter may be likened to the experience of holding a kaleidoscope up to the light and watching its multiple surfaces refract through the movement of reflected light in time and space. Hunters life and art deserve study from different perspectives because there are so many fascinating entry points to her life: self-taught artist, memory painter, diarist, woman, southern African American, and American artist, among them.

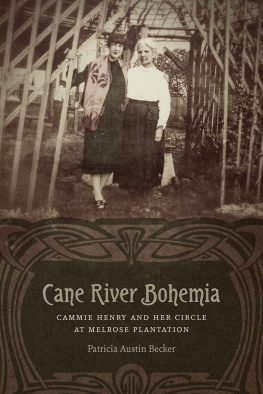

Hunter was sixty-seven years old when she undertook her most ambitious artistic work: painting the African House Murals at Melrose Plantation, a project conceived by Franois Mignon, the plantations curator. Hunters understated acceptance of the commissionI dont mind, she reportedly said suggests that she felt up to the challenge. She took on the daunting project at an age when most women are on a reduced work schedule or retired, but even more extraordinary than the physical and mental energy she summoned to complete successfully the nine large panels that would cover the four walls of the room was the speed at which she did it: six weeks during one hot summer, June 8July 21, 1955.

Like that of many self-taught artists, Hunters artwork arose from the wellsprings of experience, imagination, and talent. Expressing themselves in a singular, direct style, Hunter and others were designated American folk artists, a category that garnered attention early in the twentieth century (191020) with the emergence of a canon based on art historical criteria.

In 1910 precisionist artist Charles Sheeler began to study Pennsylvania folk art, architecture, and Shaker design. As participants of Hamilton Easter Fields Ogunquit (Maine) School of Painting and Sculpture and nearby artists colony (1913), modernist artists such as Marsden Hartley, Bernard Karfiol, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Gaston Lachaise, Robert Laurent, Niles Spencer, and William Zorach became fascinated with Americana. The artists were intrigued by the nineteenth-century weathervanes, decoys, toys, chalk figures, artisan portraits, and hooked rugs that decorated the fishing shacks they occupied. Americana, the term Field gave these vernacular objects, was also collected by artists Peggy Bacon, Alexander Brook, Charles Demuth, and Elie Nadelman. Nadelman and his wife, Viola, were such enthusiastic collectors, they opened the Museum of Folk and Peasant Arts (1926) on their estate in Riverdale, New York. The pared-down formal style of these works as well as the directness of the expression, subject matter, and handling of materials resonated with modernist aesthetic sensibilities.

Further reflecting the popularity of American folk art were the Whitney Studio Club exhibition organized by Henry Schnakenberg (1924) and the Early American Art Exhibition of American Folk Painting (1930) in connection with the Massachusetts Tercentenary Celebration, organized by three Harvard University undergraduates. By 1929 the contemporary art dealer, Edith Gregor Halpert, whose artist husband, Samuel, summered at the Ogunquit colony (1926), introduced American folk art at her New York City Downtown Gallery. Recognizing enthusiasm for the art, Halpert, Holger Cahill, and Beatrice Goldsmith founded the American Folk Art Gallery within it (1931).

The person most responsible for codifying American folk art using art historical aesthetic criteria was Holger Cahill, who early on curated two exhibitions of American folk painting at the Newark Museum: American Primitives: An Exhibit of the Paintings of Nineteenth Century Folk Artists (1930) and Folk Sculpture: The Work of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Craftsmen (1931). Cahill built on the momentum these exhibitions generated by organizing the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition Art of the Common Man in America, 17501900 (1932), whose catalog essay discusses self-taught American artists and craftsmen discovering individual qualities within communal traditions and contexts.

In his book Masters of Popular Painting (1938) Cahill claimed that folk art was based on early craft traditions with historical precedents; he broadened this notion to emphasize the highly personal and unique styles of self-taught artists. Cahill named nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists who interested early collectors and museum professionals: Edward Hicks, John Kane, Lawrence Lebduska, Joseph Pickett, Horace Pippin, and Patrick Sullivan were exhibited as popular painters, an American response to Frances Douanier, Henri Rousseau, first noticed by Pablo Picasso and his friends. Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, never called the talented painters in the book folk artists. Cahill referred to them as Artists of the People. Like their anonymous predecessors, they were all self-taught.

In 1937 twelve carved works by the self-taught Tennessee artist William Edmondson were exhibited at MoMA, the first public exhibition of work by an African American. Two years later the New York art dealer Sydney Janis, an ardent supporter of contemporary self-taught artists and active on MoMAs Advisory Board, launched a project called Contemporary Unknown American Painters, consisting in part of an exhibition in the Members Room of the museum. The same year an idealistic southern artist named Charles Shannon, an affiliate of the New South Art Center, met Bill Traylor on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, and began collecting his drawings. Shortly thereafter, Janis wrote and self-published They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the Twentieth Century (1942), a book that featured thirty painters, among them Morris Hirshfield, John Kane, Anna Mary Robertson Grandma Moses, Joseph Pickett, Horace Pippin, and Patrick Sullivan.

BATON ROUGE

BATON ROUGE