Marilynne Robinson

Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution

For Fred, James, and Joseph With thanks to Melissa Gordon

While nations consent to put into any hands an uncontrollable power of mischief, they may expect to be thus served.

Jeremy Bentham

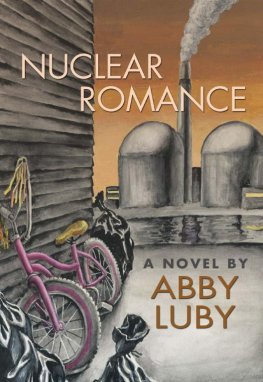

Perhaps the real subject of this book is the fact that the largest commercial producer of plutonium in the world, and the largest source, by far, of radioactive contamination of the worlds environment, is Great Britain and that Americans know virtually nothing about a phenomenon that occurs, culturally speaking, so very close at hand. The primary producer of plutonium and pollution is a complex called Sellafield, on the Irish Sea in Cumbria, not far from William and Dorothy Wordsworths Dove Cottage. The variety of sheep raised in that picturesque region still reflects the preference of Beatrix Potter, miniaturist of a sweetly domesticated rural landscape. The lambs born in Cumbria are radioactive. This fact is ascribed to the effects of the Russian nuclear accident at Chernobyl, but Sellafield is so productive of contamination that there is no reason to look elsewhere for a source. Testing of lamb and mutton was only undertaken some months after Chernobyl, though the plant at Sellafield routinely releases plutonium, ruthenium, americium, cesium 137, radioactive iodine, and other toxins into the environment as part of its daily functioning. The fact that food had not been tested systematically in an area whose economy is based on the production of food as well as the production of plutonium is characteristic of British policy, wherever there is a potential impact of industrial practice on public health.

It should be noted that the plant at Sellafield was built by the British government. It was developed and operated by the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority, and then given over to British Nuclear Fuels Limited, a company wholly owned by the British government. It should be borne in mind that the plant receives waste and reprocesses plutonium for profit, to earn foreign money. Sellafield is at the center of an economic configuration of a kind as yet unfamiliar to Americans. It is a part of the electrical-generating industry because it absorbs the wastes produced in British reactors, transforming them, in part, into salable materials through reprocessing. It expedites the sale of British nuclear technology abroad by accepting wastes generated in other countries, the costs of engineering services and waste disposal lowered by the value of these reprocessed materials. It is a closed cycle (putting aside the fact that the public subsidizes it once in the price they pay for electricity and again because of its military role as supplier of plutonium for British bombs) in which each stage stimulates profitability in the others. To call a government-run industry highly profitable, when on the one hand it is the monopoly supplier of a very costly product, as electricity is in Britain, and on the other hand it is incalculably destructive of the public health, seems to cause no embarrassment to the plants defenders. The British nuclear industry creates leukemia in the young and hypothermia in the old, and yet it is profitable. Clearly bookkeeping is as expressive of cultural values as any other science.

Sellafield has flourished in the care of Labour and Conservative governments alike for thirty-five years, during which time it has poured radioactive wastes into the sea through a pipeline specially constructed for that purpose, creating an underwater lake of wastes, including, according to the British government, one quarter ton of plutonium, which returns to shore in windborne spray and spume, and in the tides, and in fish and seaweed and flotsam, and which concentrates in inlets and estuaries.

The plant is expanding. Wastes from European countries, notably West Germany, and from Japan, are accumulating there, while the British develop means of accommodating the pressing world need for nuclear waste disposal. Their solution to the problem amounts to extracting as much usable plutonium and uranium from the waste as they find practicable and flushing the rest into the sea or venting it through smokestacks into the air. There are waste silos, some of which leak uncontrollably. In an area called Driggs, near Sellafield, wastes are buried in shallow earth trenches. Until the practice was supposedly ended in 1983 by the refusal of the National Union of Seamen to man the ships, barrels of nuclear waste were dropped routinely into the Atlantic. In other words, Britain has not solved the problem of nuclear waste, has in fact greatly compounded it, in the course of producing plutonium in undivulged quantities.

What happens to this plutonium once it is extracted no one says. We must depend on the wisdom and restraint of the British government to keep it from falling into the wrong hands. Yet one arrives fairly promptly at the realization that the only prospect as alarming as that all this plutonium should fall into the hands of irresponsible or malicious people is that it should remain in British hands. The essential act of irresponsibility is, after all, to have produced it in the first place. And then the British are not especially fortunate. Sellafield itself has had about three hundred accidents, including a core fire in 1957 which was, before Chernobyl, the most serious accident to occur in a nuclear reactor. Sellafield was called Windscale originally, until so much notoriety attached itself to that name that it had to be jettisoned. That an accident-prone complex like this one should be the storage site for plutonium in quantity is blankly alarming.

There are many useful lessons to be learned about the nature of contemporary history from the study of Sellafield. Most informed Americans believe that the release of plutonium on an important scale into the environment would entail disaster of world historical proportions. Yet every account of our present situation sees grand-scale plutonium contamination as a threatened consequence of the competition of the so-called superpowers. In other words, the account we make of present history is radically in error, not least in the matter of the importance of the United States and the Soviet Union in determining the fate of the earth. If plutonium deserves its reputation, then a nuclear war will simply accelerate the inevitable. Statesmanship in Moscow and Washington will merely postpone the inevitable. This is to say that decisions of the greatest consequence have been taken, while our savants and moralists looked resolutely in the wrong direction. We have pondered the Russian soul, and our own, and we have seen the darkness in them both as deviation from the human norm. Western Europe and especially Britain we have assumed to be mild with age, peripheralized by the drift of history. Yet any final reckoning would probably find Britains impact on the postwar world greatest of all nations. Fleets sail away, ideologies talk themselves to death, empires yield to cultural tectonics. But plutonium is everlasting, for human purposes, and it is irretrievably a part of the world environment, because the British have made a business of pumping it into a shallow sea through a pipeline a mile and a half long, and have prevented no one from fishing in the area, though the fish are radioactive, five thousand times more so than fish caught in the North Sea, though that is also contaminated. They have prevented no one from living or vacationing there, or growing and marketing food in a countryside affected by radioactive wind and rain. Plutonium from the plant carried by the sea has already been found in Ireland, Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium.

I am aware that the situation at Sellafield raises a great many questions as to how and why such a thing should have come about. But the fact of the plants existence and operation is not disputed it can be confirmed by anyone in America who cares to spend a few hours in a fairly good library looking at British publications. The mystery is not how a phenomenon of this importance can be concealed but how, being, as it were, a city on a hill, it has remained unknown to us for so many years.