Contents

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

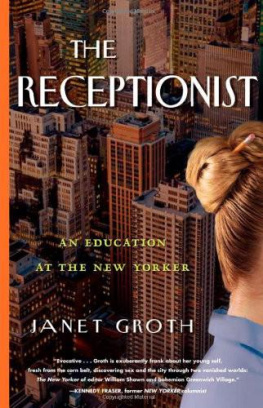

2012 by Janet Groth. All rights reserved.

The following were first published elsewhere in slightly different form: Homage to Mister Berryman appeared in the New England Review, Volume 29, Number 3, 2008. It was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and won honorable mention in the Pushcart Prize volume, 2008.

Lunching with Joe appeared in Southwest Review, Volume 93, Number 4, 2008.

eISBN 9781616201586

H OMAGE TO M R. B ERRYMAN

F OR A BRIEF PERIOD in 1960 when he was in New York on academic vacation, the poet John Berryman was of the opinion that I would make him a good wife. He proposed this to me regularly. It seems he was, in the years between his second and third marriages, proposing to every halfway decent-looking woman he met. It was perhaps his way of acknowledging guilt at the failure of his previous marriages and an indication of his good intention to do better next time. Late in the sixties, at a womens group, he came up when the issue of male commitment aroseas an example of overcorrection. Among the seven women in the room, it turned out that he had proposed to three of us. And that was only in New York, in his spare time. Th e campuses where he taught in those bachelor years, 195961, were checkered with other potential Mrs. Berrymans. So it was perhaps not the mark of distinction it seemed in the moment.

John Berryman came into my life in 1956 as my teacher at the University of Minnesota. He was then a clean-shaven professor of humanities, teaching the classics from the Greeks to Shakespeare. Once exposed to his electrifying classroom technique, I took every class he offered. Th en, once hed begun to recognize me, after two or three semesters, I tagged along when he invited the best and the brightest of his students out for coffee and further discussion after class. Brilliant Jerry Downs was trained by the Jesuits, and troubled. I was bright enough to sit next to him, share notesand Berryman. Jerry adored him, too, and when lucky enough to be asked, we would sit with him in some campus greasy spoon for an hour after class, or as long as Berrymans cigarettes held out. Th ere, in a haze of smoke, Mr. Berryman, as we called him, held forth with ideas about everything from the text we were reading to his days at Clare College, Cambridge. He harbored nostalgic yearnings for those ivied halls, snowbound as he was in the wild terrain of northern Middle America.

A couple of years after my graduation, he reentered my life in his capacity as poet. On one of his visits to the office of Louise Bogan, the poetry editor of Th e New Yorker, he discovered me behind a desk on the editorial floor. Invitations to lunches and dinners ensued.

He had a personal triangle of stopping places when he was in Manhattan, from the Chelsea Hotel, to Chumleys on Bedford Street, to the White Horse on Hudson. My apartment was on Jane Street and so formed an insert in the baseline of his larger configuration. He would stop by, shouting his newest Henry poem, more pleased by it, more acute about its merits, chagrined about its weak lines, and acute about those, too, than any outside commentator could be.

His courting was full of high-flown compliments about the magnificence of my face, the golden flamingness of my hair, the metamorphosis of my body from its former student shape into what he perceived as its present womanly glories. But these remarks had a professorial, ex cathedra air about them. Th e real text of his conversation was more likely to be concerned with what he was writing, where he was reading his poems, how he was faring on one of his projects or another, or, with lapses into intimacy, something that his sonon a postdivorce visitmight have said to him as he watched his father shave. Berrymans talk was fast and compounded of so many diverse elements that ran into each other at such dizzying speed that I found it impossible to react. I felt vaguely stunned in his presence.

He never touched me except to draw his stretched-out second finger down the side of my face. I saw little of him, far too little to have justified his conviction that I would make him a good wife. Th ere was only the occasional visit with a new poem and heavy compliments, or a telephoned summons to meet him at one of the points on his triangle, where there were sure to be others present. Youngsters, out on a date, hugged themselves and their beer mugs with delight at having stumbled on an evening with an authentic geniuseccentric, a poet, and in his cups.

So we made the rounds, or rather the angles, John dropping the great names of his famous friends, Cal and Saul and Delmore, and, when he was at the White Horse Tavern, of Dylan Th omas, another poet who drank more than was good for him. I sensed that he was both hurt and angry that he was not included in the ranks of those great and famous friends, had not achieved more, been recognized more. I knew, too, that he was hoping for the offer of a chair at Columbiawith what encouragement I am not sure, but he spoke of it as the hinge on which to swing our marriage. It did not seem to be forthcoming. I could not have married him anyway, for I was in love with somebody else. But it was clear that John was going through a bad time, and the time never seemed right for me to tell him that.

When I managed a diplomatic refusal, he went back to Minnesota. In the following year he married a young woman from Saint Paul called Kate. I became a person he looked up when he came into town from his many travels, to India and Dublin and elsewhere. Kate waited at home in Minnesota with a new baby and hopes of his recovery from alcoholism. He would call asking me to meet him somewhere, and I would arrive, only to discover that in the interim he had moved on. I might or might not go after him. If I did not, I would be treated to an early-hour rousting out of bed to find a weary cab driver supporting him on my doorstep. He had remembered, with sorrow, our broken date. I might get him to take a little coffee or tea as he sagged on my living room couch, smoking French cigarettes. He would not hear of sleep, not even when he was unfit for conversation. What helped was music. Certain Mozart quartets or any of the Brandenburgs commanded his reverent attention even when he could not speak.

Th e last time I saw John he was bearded and very famous indeed, having won a Pulitzer for 77 Dream Songs. He, drunk and shirtsleeved and rambling; his publisher, Robert Giroux, sober and correct and embarrassed; and I, also sober, also correct, also embarrassed, met, supposedly to lunch, at Girouxs apartment on the Upper East Side. John came to the door bearing a water tumbler of bourbon in his trembling hand. Beads of cold sweat stood out on his forehead. Bob Giroux and I bounced worried suggestions off him about food and doctors, rest and warm baths. He would not hear a word from either of us. His talk was difficult to follow but brilliant. Among other, more personal comments about how fine I was looking and what sort of terms he hoped to get for his next book, he delivered a tercentenary tribute to Jonathan Swift and told us about a visit he had paid when he was a student at Clare College to the aged and oh-so-awe-inspiring Yeats, at which, as John recalled it, he tried to one-up Yeats. Th en he shouted a few poems at us. Th en, out nearly cold on the sofa, he made heartrending reference to what he knew he was doing, couldnt seem to stop himself from doing, to his wifewhose temporary retreat to New England with their child he applauded as awfully wise. Th is outburst was followed by the emotionless invocation, Please, God, let me be dead soon. It seemed as if he might at least sleep.

Next page